Part One

Na na na nana na, nana na na na nana na na…

Why does The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down continue to move us over 50 years after The Band first recorded it?

The fact that so many people continue to debate its meaning online (see links here, here, here and here) is a mirror of America’s ongoing uncertainty about the motives of the Civil War’s opposing sides, of its resolution and of its meaning for our time. In other words, the war (and the Viet Nam war during which The Night was composed) is still not over.

Music critic Ralph Gleason wrote:

Nothing I have read…has brought home the overwhelming human sense of history that this song does. The only thing I can relate it to at all is ‘The Red Badge of Courage’. It’s a remarkable song, the rhythmic structure, the voice of Levon (Helms) and the bass line with the drum accents and then the heavy close harmony of Levon, Richard and Rick in the theme, make it seem impossible that this isn’t some traditional material handed down from father to son straight from that winter of 1865 to today. It has that ring of truth and the whole aura of authenticity.

Even though the lyrics might play a bit loose with the truth, we’re talking about emotional authenticity. And for this reason, The Night has always been particularly challenging for progressive people, because it forces us to consider the internal experience of someone most of us would have considered an enemy. It forces us into a confrontation between our politics and our innate empathy for those who suffer.

In a mere three verses, the song evokes a fundamental aspect of American myth, with all its complexity and ambiguity, the war of brother against brother. And that story in turn directs us to a similar conflict within every soul. Every American is – or should be – struggling with the paradox of identity, between our national ideals and the realities of our actual behavior in the world.

But it condenses its tragic nature into the story of one Confederate veteran, Virgil Caine, who makes no claim for anyone else, a man who is clearly too poor to have ever owned slaves. Indeed, the song never mentions race, slavery, state’s rights or the issue of secession. He simply wants us to understand, writes Greil Marcus, “…that the war has cost him everything he has.”

It is hard for me to comprehend how any Northerner, raised on a very different war than Virgil Caine’s, could listen to this song without finding himself changed. You can’t get out from under the singer’s truth – not the whole truth, simply his truth – and the little autobiography closes the gap between us. The performance leaves behind a feeling that for all our oppositions, every American still shares this old event; because to this day, none of us has escaped its impact. What we share is an ability to respond to a story like this one.

In the first verse we learn:

Virgil Caine is my name and I served on the Danville train

Til Stoneman’s cavalry came and tore up the tracks again

In the winter of ’65 we were hungry, just barely alive

By May the 10th Richmond had fell, it was a night I remember oh so well.

Chorus:

The night they drove old Dixie down and all the bells were ringing

The night they drove old Dixie down and all the people were singing

They went, Na nana…

Caine remembers the winter of 1865, close to the end of the war, when his unit unsuccessfully attempted to stop Union General Stoneman’s scorched earth strategy of destroying all crops and resources (tore up the tracks again) that might have enabled the Confederacy to defend its capital. Historian Bruce Catton writes:

(Ulysses S.) Grant’s instructions were grimly specific. He wanted the rich farmlands so thoroughly despoiled that the place could no longer support a Confederate army; he told (General Phillip) Sheridan to devastate the whole area so thoroughly that a crow flying across the Valley would have to carry its own rations…Few campaigns in the war aroused more bitterness than this one.

David Powell writes:

Even though Stoneman, on the surface, may appear to be just a footnote in the history of the Civil War, in that part of the U.S. where the borders of Tennessee, North Carolina & Virginia meet, his name lives in infamy. The exploits of his plundering cavalry troops in the last days of a defeated Confederacy are still a part of local legend.

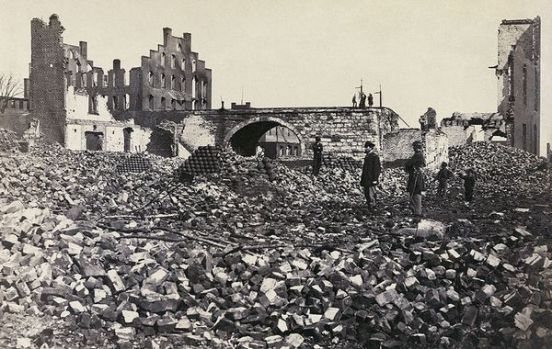

The siege of Richmond lasted ten months. Before retreating on April 2nd, the Confederate Army set much of the city on fire to deny Union troops any usable resources. The overcrowded civilian population was starving. (May 10 marked the capture of President Jefferson Davis.)

Can we – are we willing to – imagine the suffering? Does it matter that these people had supported a cruel and unjust system? Does it matter that Americans then and now often prefer not to experience grief but rather to turn it into denial, resentment and racialized victimization?

A full assessment of that moment must include the African American voice. Garland White was chaplain to the 28th Indiana Colored Volunteers, the first Federal soldiers to enter the burning city:

A vast multitude assembled on Broad Street, and I was aroused amid the shouts of ten thousand voices, and proclaimed for the first time in that city freedom to all mankind. After which the doors of all the slave pens were thrown open, and thousands came out shouting and praising God, and Father, or Master Abe, as they termed him…We made a grand parade through most of the principal streets of the city, beginning at Jeff Davis’s mansion, and it appeared to me that all the colored people in the world had collected in that city for that purpose…The excitement at this period was unabated, the tumbling of walls, the bursting of shells, could be heard in all directions, dead bodies being found, rebel prisoners being brought in, starving women and children begging…I was with them, and am still with them, and am willing to stay with them until freedom is proclaimed throughout the world.

But suffering is suffering. Back with his wife in Tennessee, Virgil Caine is not concerned with retribution or punishment. He merely asks us to know his despair.

That despair, however, is set within a mythic theme: The Lost Cause. For generations after the war, white Southerners, in an extended but highly selective memory, mourned the destruction of a noble, refined, chivalrous “way of life.” The myth explained their military defeat with a story that only the North’s massive numerical and industrial force could overwhelm the South’s superior military skill, gallantry and courage. The myth, of course, does not care to examine the underlying causes of the war. That’s one reason why it still retains such emotional resiliency.

It had, claimed this myth, not been a fair fight. It had, however, been a four-year slaughter that expressed a different and much older narrative. The armies, predicting the far greater destruction to come in 1914, were enacting the old myth of the sacrifice of the children. As I write in Chapter Eight of my book Madness at the Gates of the City, the Myth of American Innocence:

War became impersonal and industrialized, with the objective of maximizing the killing. But even though technology had changed things irrevocably, tactics didn’t change; old men sent young men marching in closed ranks against massed cannonry and repeating rifles. Six hundred thousand died and 500,000 were wounded, in a country of thirty million. One-fifth of the South’s adult white male population perished.

A hundred and fifty years later, we wonder why several hundred thousand dirt-poor whites who couldn’t afford to own slaves defended this cause so savagely. We must conclude that they fought not to save slavery (which was against their own economic interests), but to perpetuate white privilege. It was all they had.

We could also ask why the descendants of these people continue to vote against their own economic interests, and we have to conclude, as I did here, that the fear of losing their white privilege remains their primary motivation. We could also ask whether the South actually won the war.

The song, however, says nothing of these things. To Virgil’s credit, we can assume that his primary motivation had been simply to defend his family. And he had been unsuccessful. The South was the only American region to ever undergo occupation by an enemy power. Below the glorious myth of the Lost Cause, there remained a deep sense of crushing, humiliating defeat, followed by the Reconstruction period, during which, in many cases, Black men actually governed white men.

Robertson (a Canadian and a Native American) writes of his first visits to the South in the late 1950s – when local White people feared that once again a beautiful system might be disrupted, this time by the Civil Rights movement:

I remember that a quite common expression would be, “Well don’t worry, the South’s gonna rise again.” At one point when I heard it I thought it was kind of a funny statement and then I heard it another time and I was really touched by it. I thought, “God, because I keep hearing this, there’s pain here, there is a sadness here.”

Second Verse:

Back with my wife in Tennessee when one day she called to me

`Virgil, quick come see, there goes Robert E. Lee’

Now I don’t mind choppin’ wood and I don’t care if the money’s no good

You take what you need and leave the rest, but they should never have taken the very best.

There is deliberate ambiguity here. Does his wife see the fabled General Lee himself riding by their Tennessee farm – or is the steamboat “Robert E. Lee” passing by on the river? It really depends on which record you hear. On The Band’s final recording of the song (the film The Last Waltz), Levon Helm seems to be adding a “the” in front of the General’s name:

In any event, Virgil seems to have a brief, final glimpse or memory of the man who personified the cause, the officer he once would have died for. But the memory soon fades, and he is left with the grim reality of having to chop wood (probably for someone else) for a living, because his Confederate dollars are worthless.

But the vision of the great man has stimulated something else. Exactly whom is Virgil addressing when he laments, “You take what you need and leave the rest”? The Northern soldiers and carpetbaggers? A generalized “you”? Himself? I don’t think so. I think that he’s addressing General Lee and all of his generation on both sides, all of the politicians, industrialists, plantation owners, clergy, newspapermen and anyone else among the fathers who sat comfortably in their armchairs as their sons marched into the furious cannonades at Gettysburg, where over fifty thousand were killed or injured in three days.

He is addressing the great God Kronos, who heard a prophesy that one of his sons would overthrow him and attempted to eat them all to prevent that from happening.

“…They should never have taken the very best,” wails Virgil, thinking undoubtedly of his brother who will die in the third verse. What Virgil doesn’t understand, however, is that the point, the very essence of human sacrifice is in fact to offer up the very best of the younger generations to the infinite hunger of the gods of the new order. How else to justify the madness of history but through such sacrifice: It must have been worth it! Look what we gave up!

Part Two

In the Bible Cain slew Abel and East of Eden he was cast. You’re born into this life paying for the sins of somebody else’s past. – Bruce Springsteen

Here is the third Verse of The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down:

Like my father before me I will work the land

Like my brother above me who took a rebel stand

He was just 18, proud and brave, but a Yankee laid him in his grave

I swear by the mud below my feet, you can’t raise a Caine back up when he’s in defeat.

The ambiguity of the earlier stanzas continues: many people have heard the first line of this verse as “Like my father before me I’m a working man.” Still more: as Virgil sings of his dead brother he makes a pun on the small mischief people used to describe as “raising cane.” But the real issue here is that, by repeating his surname (and his brother’s surname), Virgil evokes another Biblical myth, the original war between brothers that we all know as the story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4), the model for all subsequent wars.

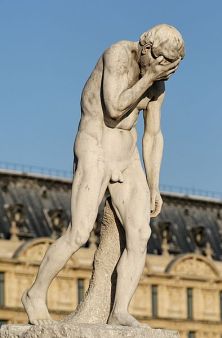

Cain was the first human to be born and Abel was the first human to die. Cain, refusing to be his “brother’s keeper,” murdered Abel out of envy. Cain had offered “some of the fruits of the soil as an offering to the Lord.” But God favored the shepherd Abel, who offered “fat portions from some of the firstborn of his flock.”

“The First Mourning (Adam and Eve mourn the death of Abel)” by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

“The First Mourning (Adam and Eve mourn the death of Abel)” by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

Was it God, as Robertson sings, who had taken the very best? And when he heard of the subsequent murder, he cast the first curse:

The Lord said, “What have you done? Listen! Your brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground. Now you are under a curse and driven from the ground, which opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand. When you work the ground, it will no longer yield its crops for you. You will be a restless wanderer on the earth.”

Still, Cain received a mark of protection from God, who allowed him to marry and have children. In pop music lyrics, however, the mark is usually seen as something negative:

The landed aristocracy, exploiting all your enmity,

All your daddies fought in vain,

Leave you with the Mark of Cain. – Amy Ray, the Indigo Girls

Virgil Caine’s land will no longer support his family; he must chop wood to make ends meet. So we ask again, whom is he addressing when he cries, “You take what you need and leave the rest”? Nine years after The Night, Bruce Springsteen recorded Adam Raised a Cain, which include the lyrics at the top of Part Two Part Two and the ambiguous image of the father possibly raising a cane to strike his son.

Cain, by Henri Vidal

Ambiguity and our need to resolve it produces the emotional force that drives some songs and some myths. And there is irony here as well. According to Shi’a Muslim belief, Abel (Arabic: “Habeel”) is buried in the Nabi Habeel Mosque west of Damascus, Syria. Here in 2022 the latest war of brothers continues to rage, a war that would not be happening without American money and armaments.

Below the Cain and Abel story lies another one, as I write in Chapter Nine of my book. Our economic myths follow from our historic assumptions about the infinite resources of an “empty” American land. However,

In truth, modernity assumes scarce resources – fuel, food, education, power, freedom, knowledge and especially love. These assumptions begin in our monolithic creation myth, the expulsion from Eden, and lie, along with the compensating belief in progress, at the core of all western thought. The Old Testament provides occasional visions of plenitude (manna from Heaven); but these are followed by laws and restrictions, which, when disobeyed, result in expulsion. It is, writes (historian Regina) Schwartz, a world “where lying, cheating, stealing, adultery and killing are such tempting responses to scarcity that they must be legislated against.”

Biblical stories of fathers and sons are utterly rooted in scarcity assumptions. Isaac cannot bless both of his sons; apparently there isn’t enough to go around. Forced to compete for the blessing, they establish a pattern in which the father rejects the loser. Earlier, Jehovah preferred Abel’s offering to Cain’s. Even God doesn’t have enough blessing to satisfy everyone. Jealousy, rivalry and murder all follow. This core text of monotheism defines identity as something that is won through competition, at someone else’s expense.

More ambiguity: the line “…but a Yankee laid him in his grave” fits the meter of the song, and it certainly sounds authentically archaic. But Robertson could have written it differently and still fit it into the rhyme and meter. In the context of fratricide – death at the hands of one’s own brother – “laid him in his grave” actually sounds like a gentle act of respect and reverence, a holy ritual. Indeed, the phrase doesn’t clearly indicate that the Yankee had actually killed Virgil’s brother, only that this “proud and brave” teenager was dead. Indeed, as we consider the mythic implications, the “band of brothers” on either side of the firing line have much more in common with each other than they do with the plantation owners and industrialists – the fathers and the father gods – who have set them against each other.

To follow the Biblical tone of the stanza, all we really know is that a jealous god, holder of a very limited capacity for blessing, required – repeatedly – that brothers compete with each other. Why? To prove their worth, or simply for his own amusement? What if history and theology didn’t literalize this image? What if we knew the Latin root of “compete” as “to strive together,” or “to supplicate the gods together”? What we do know is this: that even generations later, Abraham, a member of this same family, would be willing to sacrifice his only son to prove his worth before this same god.

Our American myth of (white) brother-against-brother offers us a seemingly happy ending. The nation was torn asunder and then reborn when Reconstruction ended. But it could only do so by colluding in a newer but equally toxic story in which the original wounds of racism were covered over rather than healed. The wounds sat festering for another hundred years, as I write:

Fratricide perfectly describes the impact of the war upon the American soul, which more than that of any other nation is split against itself. The word evokes such emotion precisely because Americans still hope to heal that split in the psyche. Contemporary battle re-enactments express this longing. Because the issue of race went unresolved, however, the nation achieved only a superficial healing.

We are back to the sacrifice of the innocents, and I invite you to consider the first verse once again: In the winter of ’65. The song does not say eighteen-sixty five. Am I seeing too much here? Of course the song is about the American Civil War, and of course it describes the last year of the war. And yet…Robertson wrote it when the Viet Nam war was at its height, when a hundred Yankees were being laid in their graves every week. And yet…for every American death there were hundreds of Vietnamese deaths. His original 1969 version was followed two years later by the Joan Baez version, which, sung by a woman and civil rights activist, added both pathos and more paradox. Martin, Malcolm and the Kennedys were dead; perhaps, writes Jonah Begone, the song could speak to a larger sense of defeat for the left, a feeling of disappointment of early promise that had gone unfulfilled.

Stoneman’s destruction of Virginia’s infrastructure and burning of its crops, resulting in mass starvation of the civilian population, was a war crime. This is known in international law as “collective punishment” for individual actions. It’s what the Nazis did to countless towns such as Lidice. It’s what the Hebrews did to the population of Jericho when “the walls came tumbling down”, and it’s what their descendants do every time they invade Gaza.

In 1965 Vietnamese peasants were “just barely alive”. Massive aerial bombardment and spraying of toxic herbicides over huge swaths of the country was amounting to genocide. Americans may be the only nation in history to declare the concept of “free fire zones”, and they may have learned it in 1865.

1965 saw resistance in Viet Nam and also in the streets of Watts, California – a century after the fall of Richmond, the Civil War was still raging. A half-century further on, urban police, the descendants of the Southern slave patrols, with few exceptions, can still murder an unarmed Black man with impunity.

In mythological terms, to “drive Dixie (or anyone) down” is cata-strophic, to be turned away from our obsession with the light, with the gods of the sky, with the myths of growth and national purpose, with the flights of the ego and the spirit, and back towards soul. It is to be humiliated, to return to contact with the humus, the earth. But it is also to be offered the possibility of grieving, reconciliation and healing.

So the song certainly evokes Hebrew myth (Cain & Abel), Greek myth (Kronos) and American myth (progress, scarcity). And now we can see why the narrator’s first name is Virgil. The Roman poet Virgil is best known for having composed the Aeneid, the epic that tells how Rome was founded by the last survivors of Troy, another city that, like Richmond, invaders had destroyed. A thousand years later, Dante, in The Divine Comedy, chose this same Virgil to be his guide in the underworld, the place of soul-retrieval.

Ultimately, Virgil Caine’s helpless lament is not only for the South. It is for America’s soul, and this is why The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down remains such an emotionally powerful piece of art. In a culture that continues to deny death, that condemns a quarter of its children into poverty, that refuses (like the Southern oligarchs) to accept that its time is over, that enacts the old myths of the sky gods at every opportunity, that is (in W.S. Merwin’s words) “up to its chin in shame, living in the stench it has chosen”, that has so few grief songs, we need to hear it and sing it out loud.

We need to think about Joshua Chamberlain, a general in the Union Army and hero of the Gettysburg meatgrinder, wounded six times. He was present at the awesome spectacle of Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9th, 1865, a week after “Richmond had fell.”  He looked closely, perhaps for the first time, at those starving “Jonnie Rebs” who so recently had been on the other side of the firing line:

He looked closely, perhaps for the first time, at those starving “Jonnie Rebs” who so recently had been on the other side of the firing line:

Before us in proud humiliation stood…men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now…thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond…What visions thronged as we looked into each other’s eyes!…On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer…but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!…How could we help falling on our knees, all of us together, and praying God to pity and forgive us all!…For they were fellow-soldiers as well, suffering the fate of arms…We could not look into those brave, bronzed faces…and think of personal hate and mean revenge…Forgive us, therefore, if from stern, steadfast faces eyes dimmed with tears gazed at each other…

A fine place to end. But one Confederate general refused to join the ritual of reconciliation:

You may forgive us, but we won’t be forgiven. There is a rancor in our hearts which you little dream of. We hate you, sir.

One hundred and fifty-seven years later, we admit that the South really didn’t lose the Civil War and that the Lost Cause myth is still alive. Many Southerners see The Night and other songs such as Sweet Home Alabama and I’m A Good Old Rebel as emblems of regional pride.

However, a study of history and psychology should also remind us that it took – and continues to take – massive amounts of money and continuous, overwhelming marketing to manipulate the white working class into ignoring their own best economic interests and the possibility of solidarity with other oppressed people in favor of the politics of hatred. This fact alone should remind us that people are not inherently biased against each other. We have to be taught to hate.

And not all Southerners are charged by the old myths. One challenge for an artist, especially one born to privilege, is to reframe them, or in this case to re-write song lyrics, as Early James did with The Night.

In the first verse, he changes a time I remember oh so well to a time to bid farewell. His version of the chorus, instead of mourning that downfall, is Tonight, we drive old Dixie down.

Most notably, in his final verse, he rejects both the Lost Cause and the myth of the Killing of the Children:

Unlike my father before me, who I will never understand

Unlike the others below me, who took a rebel stand

Depraved and powered to enslave

I think it’s time we laid hate in its grave

I swear by the mud below my feet

That monument won’t stand, no matter how much concrete…

What do we conclude from all this? We need as many grief songs as we can find. We need to constantly interrogate our mythic productions (including popular music) and reframe them for our children. And as for our history of demonizing the “Other”, I like what the Hindu sage Ramana Maharshi said: “There are no others.”