I was a racketeer, a gangster for capitalism…I could have given Al Capone a few hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three districts. I operated on three continents. – General Smedley Butler

I laughed to myself… “Here we go. I’m starting a war under false pretenses.” – Admiral James Stockdale, on the Gulf of Tonkin incident

I will never apologize for the United States of America. I don’t care what the facts are. – George H.W. Bush

We are grateful to the Washington Post, the New York Times, Time Magazine…whose directors have attended our meetings and respected their promises of discretion for almost 40 years. – David Rockefeller

If any question why we died, tell them, because our fathers lied. – Rudyard Kipling

The Greatness of War

Veterans Day became an official national holiday in 1954, after a multi-decade evolution. It coincides with Armistice Day and Remembrance Day, celebrated in other countries that mark the anniversary of the end of World War One.

The Great War slogged on for over four years.

Estimates of the casualties range from a low of eleven million dead combatants – which translates to 7,000 dead per day, every day, for those four years – upwards to 41 million total casualties, including perhaps eight million civilian deaths. These numbers do not include the “Spanish Flu” pandemic of 1918, which resulted in the deaths of another 50 to 100 million people (three to five percent of the world’s population).

The date of November 11th commemorates the formal ending of hostilities at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, when the armistice went into effect.

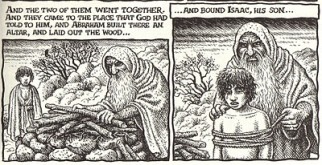

So much for the numbers. Now for the mythic implications. Indeed, only a deeply- and widely-held mythology can even begin to explain the numbers. Chapter Six of my book discusses the Sacrifice of the Children, which I consider to be the most fundamental mythic narrative underlying all of Western Culture:

which I consider to be the most fundamental mythic narrative underlying all of Western Culture:

Ultimately, sacrifice – dying for the cause – became as important as physical survival. Martyrdom became an ethical virtue that every believer must be prepared to emulate. “Uniquely among the religions of the world,” writes (Bruce) Chilton, “the three that center on Abraham have made the willingness to offer the lives of children – an action they all symbolize with versions of the Aqedah (the sacrifice of Isaac) – a central virtue for the faithful as a whole.”…This is how Patriarchy perpetuates itself. In each generation, millions of abused children identify with their adult oppressors and become violent perpetrators themselves. In a demythologized world, they have no choice but to act out the myths of the killing of the children on a massive scale…And what of those who direct the carnage? War allows the old to enact the sacrifice of the children. They project their ambivalence toward their own uninitiated, “inner” children onto actual soldiers, while safely and vicariously experiencing Dionysian intensity. War is an end disguised as a means: deferred infanticide, the revenge of the old upon the young.

What led to this state of affairs? In Chapter Eight I write about the decline of religion in the late 19th century and the ideology of nationalism that replaced it in all “developed” countries:

Ouranos and Kronos ruled the unconscious of modern man. Now everyone was judged by how useful they were under capitalism. In 1900 George Simmel wrote that existence in the urban factories had diminished human passions in favor of a reserved, cynical attitude. This had created a compensatory craving for excitement and sensation, which for some was partially satisfied by the emerging consumer culture. But others needed something even more extreme, more Dionysian, to make them feel alive…This damage to the soul occurred along with the most rapid technological changes in history. One Frenchman fated to die in the first weeks of the Great War said that the world had changed more since he had been in school than it had since the Romans. In the thirty years between 1884 and 1914, humanity encountered mass electrification, automobiles, radio, movies, airplanes, submarines, elevators, refrigeration, radioactivity, feminism, Darwin, Marx (who wrote, “All that is solid melts into air”), Picasso and Freud. It is particularly ironic that just as modern people were learning of the unconscious, they were forced to act out the old myths of the sacrifice of the children. The pace of technological change simply exceeded humanity’s capacity to understand it, and the pressure upon the soul of the world exploded into World War.

How did this play out on the battlefield? Any honest military historian will admit that the generals, or in this context, the ritual elders, learned absolutely nothing in those four years. They began in August 1914 by exhorting the troops with Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori (It is a sweet and noble thing to die for your country) and then sending wave after wave of nineteen-year-old infantrymen against massed, fortified machine guns. Hundreds of thousands died in the first four months. Yet in late 1918 the generals were doing exactly the same thing. The great poet Wilfred Owen wrote this poem to describe the soldiers’ experience:

DULCE ET DECORUM EST

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of tired, outstripped Five-Nines that dropped behind.

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime. . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est

Pro patria mori.

On November fourth, a week before the already-planned armistice, the Generals sent Owen’s unit in yet another daylight – the common descriptor is “suicidal” – frontal assault against impenetrable defenses. Owens and most of his comrades were, predictably, mowed down.

Then came November eleventh, when all across the Western and Eastern Fronts, everyone was to lay down their arms at precisely 11:00 AM. You can read about that morning in Eleventh Month, Eleventh Day, Eleventh Hour: Armistice Day, 1918, by Joseph Persico.

While many soldiers refused to fight at all, others took their last chance to get revenge – and officers everywhere took their last opportunity to achieve post-war promotions. It was one of the most savage days of the entire war, resulting in another eleven thousand casualties.

Terezin

The Germans kept November eleventh alive as a shameful reminiscence of defeat. Sadly, it seems that in this demythologized world, such memories tend to bring people together – to reinforce their mythic tales of national identity – more than memories of victory (Ask any Serbian nationalist about the battle of Kosovo, which took took place in 1389). A new German mythology arose soon after the armistice that served this purpose for the returning soldiers (and the industrialists): the defeat had been caused not by the failure of the army but by treachery behind the lines. The mythmakers designed this story to uphold German masculinity and nationalism as the ideology that had replaced religion and would soon lead to totalitarianism and genocide.

On November eleventh 1943, the Nazi S.S. memorialized the 25th anniversary of the armistice with a display – uncommon even for them – of gratuitous cruelty. They forced the 40,000 residents of the Terezin ghetto in Czechoslovakia

to stand at attention in a freezing, rainy field all day for a head count that didn’t happen until late afternoon. Anyone who moved was shot. Three hundred collapsed and died before they were allowed to return to their barracks.

Why do I write this? To remind you that many of those S.S. officers went home at the end of their shifts to spend quality time with their wives and children – as did real-life American CIA officer and torture supervisor Dan Mitrione (in the 1972 film State of Siege).

These people were not inherently evil; to make them so in our imagination is merely to reinforce our own fiction of pure innocence. It is to point out the mythic and ritual realities behind our behavior in wartime, and the reasons the elders send the young to war. It is to acknowledge that such circumstances are designed, consciously or not, to take impressionable people and inject them into situations that bring out the worst in them, not the best.

Viet Nam

Progress: At least the generals had finally learned that it was useless to send massed infantry against machine guns, right? Wrong. Throughout the war, the army’s primary tactic—“search and destroy”— was the sacrifice of infantry units in order to push out the concealed enemy. This tactic was also called target acquisition. Helicopters dropped troops intentionally into “hot zones,” where they were often pinned down by enemy fire. They suffered until air strikes hit the enemy positions, and then the American survivors left the terrain to the enemy’s survivors.

Sociologist William Gibson writes, “Story after story…concerns commanders who knew large enemy formations were in a given area, but did not tell their subordinates because they did not want them to be cautious.”

In countless other examples, the Army spent massive expenditure of material and lives to force the North Vietnamese off of steep mountains for no discernable purpose. The 1987 movie Hamburger Hill depicts the nine-day assault on “Hill 937”, designated as such from its being 937 meters high. It ends with the Americans celebrating their victory. What it doesn’t show, however, is that the American abandoned the hill two weeks later.

Abandonment and betrayal became the primary metaphors for hundreds of thousands of Americans. Psychologist Jonathan Shay quotes one veteran: “The U.S. Army…was like a mother who sold out her kids to be raped by (their) father…” The soldier’s common experience, says Shay, was violation of the moral order, or betrayal.

American conservatives would twist the idea of betrayal and use the old excuse of treachery at home to rationalize defeat after the war. Nevertheless, the mythic image of the twentieth century is the sacrifice of the children. And the emotional experience of the common foot soldier is betrayal. My article Memory, Myth, and the National Mall brings the story into the 1960s:

The trauma of the Vietnam veterans was complicated by their sense of betrayal. Most returned to their urban streets and small towns alone, mere days after being in the field. There, as we know, many were treated disrespectfully—but not, as it turns out, by antiwar protestors. After exhaustive research, sociologist and Vietnam veteran Jerry Lembcke concludes that the spitters and hecklers touted by the media were hawkish veterans of World War II, who regarded the young men as losers. It was their fathers—in hundreds of VFW and American Legion posts scattered across small-town America—who were attacking the Vietnam vets. One World War II vet observed an anti-war march and snarled, “…we won our war, they didn’t; and from the looks of them, they couldn’t.” At another rally, a Vietnam vet read the names of Texas men killed in the war, while (reported by Life magazine) pro-war hecklers yelled, “Spit at those people, spit on ‘em”. (Fred) Turner quotes a Korean War vet, as recently as 1992: “I can’t understand these Vietnam guys. They’re always crying. When we came home, we kept it to ourselves and did what we had to do”. Turner also reports that forty years after Korea, this same vet’s children fear his repeated flashbacks.

Lembcke (The Spitting Image: Myth, Memory, and the Legacy of Vietnam) concludes that the Nixon White House deliberately disseminated the “myth of the spat-upon veteran” in order to counter the fact that the Vietnam veterans were actually among the leaders of the antiwar movement. By 1970, a major argument for continuing the war was to protect the troops who were already there—and to free those who were allegedly held captive by the North Vietnamese. Similarly, Bruce Franklin argues that, following the cataclysmic year of 1968, Nixon deliberately introduced the issue of the issue of the MIA/POWs to evoke strong emotional support for a war that was becoming universally unpopular.

My article goes on to note how American elites, with the assistance of Hollywood filmmakers, made a determined effort throughout the 1980s and 1990s to rehabilitate the memory of the war as (at worst) an honorable crusade and (at best) a tragic “mistake.”

I invite you to consider, however, whether the war was really a mistake, in either economic or mythic terms. Hint: read some of the many excellent articles that historians and activists have written in response to Ken Burns’ recent PBS series here, here and here.

However, most Americans, then and now, have been quite able to separate the politics and economics of the war from the suffering of those (mostly poor and ethnic minorities) whom the fathers sent to fight it. Hence the phrase we hear so often, especially every November eleventh: Thank you for your service.

All this leads me to suggest that when you consider saying these words to a veteran today, think before you speak. What precisely will be your intention? Will it be, as veteran James Kelly writes, “…an empty platitude, something you just say because it is politically correct”? Will it “…massage away some of the guilt at not participating themselves”? Will it be “…almost the equivalent of ‘I haven’t thought about any of this’”?

Kelly also writes:

After all, despite the various reasons that people join the military, from free college, to a steady paycheck to something much more patriotic or idealistic, there is one thing we all have in common: Our passion for our country and your rights and freedoms that we swore to protect.

The Sacrifice of the Children

Full disclosure: I want to acknowledge that I am not a veteran, and I have no concrete, felt understanding of a veteran’s experience, let alone the experience of combat, wounding or trauma, or even of his or her family’s pain. But I have to tread – lightly but firmly – into this “morass” (to coin a phrase). I sincerely hope that Mr. Kelly will support this statement: We fought to defend your free-speech right to completely disagree with our reasons for fighting.

The Viet Nam War was a children’s war.

Again, from Memory, Myth, and the National Mall:

…this war was fought not by reservists or the National Guard (as in Iraq) but by teenage (disproportionately African American or Latino) draftees. One of every two Hispanics, for example, served in a combat unit, and one in five were killed. Corresponding percentages for whites were much lower. Their median age was 19: For every 21-year-old, there was a 17-year-old. Lyndon Johnson chose to maximize support by minimizing its impact on older citizens. And there were few domestic sacrifices such as increased taxes; thus the war’s debt fell on future generations. Nearly half of Americans who died had been sent to Vietnam as teenagers; 14,000 died in combat before their 21st birthdays. On the other side, 40 percent of those killed by American incendiary and antipersonnel bombs were children. And because dioxin (the active ingredient in Agent Orange) remains in the body’s DNA, 35,000 Vietnamese babies are born with birth defects annually.

These figures do not take into account the suicides or the hundreds of thousands on disability. Nor do they not take into account the “economic draft,” the real reason why most young, poor and working-class people “volunteer” – or the obvious truth that their only alternatives are gangs, pregnancy, jail or living at home into their mid-thirties while working at MacDonald’s.

No one knows how many of these people have “passion for their country,” or how many believe that it is “a sweet and noble thing to die for your country.” But the mythmakers, the gatekeepers and the warmongers will go to extraordinary lengths to convince you that they do.

Here’s my alternative to Thank you for your service:

I can never know what you went through, but I would like to hear about it, and if possible, I’m willing to share your grief.