The third archetype we need to discuss is that of the Apocalypse.

It is critical to this enquiry about rage in American life to remember that the myth of American innocence began to take form while Puritanism was still dominating all intellectual discourse and most politics in both Britain and North America. Then, the idea of “America” – and along with it, the narrative of regeneration through violence – was gestating even as religion appeared to be losing its grip on the modern mind, to be replaced by nationalism.

But from the point of indigenous people, both mass religion and nationalism are ideologies, vast systems that people construct to alleviate their alienation from the Earth and from their own souls.

Those old religious roots held fast in the underworld of modernism and put out strong “shoots” in our lifetime. Now, we are faced with the undeniable fact that Trump and the fascist police state that he threatens to enforce upon us is a direct result of the massive support he continues to receive from white, evangelical Christians. In addition to identifying with his insecurity, they support him because of their racial hatreds and fears.

Do you doubt that statement? All you need to do is check the contrasting voting patterns of black evangelical Christians.

But both groups share a fascination with the Apocalypse, and so do many of us who are attracted to the Warrior and King archetypes and their “boy psychology” versions.

A staggering percentage of Americans expect the world to end in Armageddon. In 2010, 41% of respondents said they expected Christ to return to Earth by 2050. A 2012 pollfound that over a fifth of Americans believed the end of the world will happen in their lifetime (compared to 6% in France and 8% in Great Britain). Four years later, 15% said that since God controls the climate, people can’t be causing global warming, and 11% that since the end times are coming anyway, there’s no reason to worry about it.

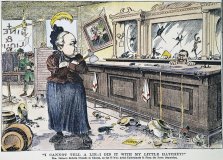

Americans inherited a long and bloody tradition of apocalyptic madness from their European forebears,  and, as I show in Chapter Seven of my book, made it an essential aspect of their national psyche, impacting several “Great Awakening” revivals and crusades against alcohol.

and, as I show in Chapter Seven of my book, made it an essential aspect of their national psyche, impacting several “Great Awakening” revivals and crusades against alcohol.  But it was also the emotional force – killing to bring on a better world – that drove the American Revolution, the genocide of the Native people and the mass slaughter of the Civil War and all our subsequent wars. Betsy Hartmann, author of The America Syndrome: Apocalypse, War, and Our Call to Greatness, writes:

But it was also the emotional force – killing to bring on a better world – that drove the American Revolution, the genocide of the Native people and the mass slaughter of the Civil War and all our subsequent wars. Betsy Hartmann, author of The America Syndrome: Apocalypse, War, and Our Call to Greatness, writes:

Of all the intertwining reasons for our apocalyptic disposition, the one that stands out most starkly is our acceptance of the necessity and inevitability of war. In the same 2010 Pew survey, six out of ten Americans saw another world war as definite or probable by 2050. This expectation of war isn’t surprising, given that Americans’ apocalyptic images and beliefs are derived mainly from Christianity, especially the Book of Revelation at the end of the New Testament which, above all, is about the grotesque violence and crowning glories of war…This promise of a New Jerusalem for the elect, and the cataclysmic violence against people and nature necessary to achieve that goal, has made the Book of Revelation an ideological tool of conquest and empire from the Crusades onwards. You don’t have to be a Christian to be susceptible to John’s logic that the perfect end—the New Jerusalem—justifies the bloody means.

A recent article proposes that we are all living in a “United States of anxiety.” But Chapter Ten of my book, published eight years ago, argued that Americans have been twisted between the two poles of fear and denial for a very long time.

Nor do you have to be a Christian to be swept up by fantasies of the end of the world as we know it, as New Age fascination with the “Y2K” phenomena  and the 2012 “Mayan prophecies” indicates. The issue we need to fully understand is what the notions of “death” or “ending” mean in myth and to the psyche. As I wrote here:

and the 2012 “Mayan prophecies” indicates. The issue we need to fully understand is what the notions of “death” or “ending” mean in myth and to the psyche. As I wrote here:

What does it mean to be at the end of an age? What does it mean to end? To honestly approach the question, we must step away from literalist thinking (whether New Age or fundamentalist) and accept that in biological, ecological, mythological or indigenous initiatory terms, to end is nothing other than to die. Only when death and decay are complete can they be understood as the necessary precursors to fermentation and potential new growth…simply focusing on the light is another form of literalization equal to religious fundamentalism. An awareness of death is precisely what I see missing in New Age thinking. To celebrate rebirth without considering the breakdown and destruction of what must precede it is to wallow in innocence. As Jung said, “…the experience of the Self is always a defeat for the ego.”

The word “apocalypse” comes from a Greek root meaning to uncover, disclose, to lift the veil from what had been concealed. Here is the essence of the issue: “End times” is a metaphor for the archetypal cry for initiation. It is our own transformation – the death of who we have been – that we both fear and long for. And our indigenous souls understand that there is no initiation into a new state of being unless we fully accept the necessary death of what came before, what no longer serves us or our communities.

Barbara Ehrenreich recently rephrased Martin Luther King, Jr.: “The arc of history is long, but it bends toward catastrophic annihilation.” She is a proud materialist and she was talking about her own inevitable death.

In our demythologized world the problem is that we no longer possess the tools to imagine inner, symbolic renewal, so we see literal images elsewhere. And we project our internal state onto the world, looking for the signs of world changes “out there.” Freud was literalizing this archetypal urge when he wrote about the “death instinct.”

It gets worse before it gets better. Several hundred years of literalization and loss of initiation rituals has limited us to a heritage in which the most psychologically damaged among us – and I would include in this population most of our mega-billionaires – can only objectify others. And they can only perceive those who deserve the symbolic death that they unconsciously desire in the Others of the world – people of color, women and gay people. For some of them, it seems to be even worse: in their mad obsession with denying climate change, do they not project their death wish upon the entire planet?

Is history cyclic? Perhaps the Paranoid and Predatory imaginations have merged once again, as they did during the crusades and the early colonial period. Or perhaps, like antibiotic-resistant bacteria, a new strain of reactionary has evolved: true believers in apocalyptic end, whose own ends justify any means. They are grandiose boy-men who subsidize murder not despite their faith but because of it. They see no ethical dilemmas in corruption and violence because their twisted mix of smug righteousness and social Darwinism assures them that their victims deserve their fate. Anyone who isn’t a hero is a victim, and all but the inner circle are now Other.

Again, I suggest: only a mythological perspective can make any sense of this. America’s rulers are not ignorant; they are fully aware of our human and environmental tragedies. The fathers no longer send only the young to be sacrificed; now they offer everything to the sky-gods. Whether or not we take their religious rhetoric literally, they are deliberately (if unconsciously) provoking both personal and global apocalypse.

Recall Pentheus, emerging from his collapsed palace, even more determined to confront (or to merge with) Dionysus. Thebes/America is a city of uninitiated men, fanatically devoted to the systematic destruction of their own children. When I was writing my book, a boy-king, who secretly longed for the symbolic death that might effect his transition to manhood, was leading this city. The entire world could almost feel it as a desperate, visceral prayer when, in June 2003, Bush, the self-appointed embodiment of American heroism, challenged the Iraqi resistance to “bring it on!”

Part Seven

We can risk psychoanalyzing the mega-wealthy. I think that on one level they really do hate themselves deeply. On another, they desperately desire renewal. And on still another level they are completely constrained by their literal thinking, their inability to think symbolically. They appear to believe that their only option is to maximize their power and privilege to call down the death of the small self upon the entire world. It could be different.

And the angry heroes who serve them? How can we re-imagine a world in which their anger is directed not at the easy targets that the right-wing presents to them, but toward the actual threats to a harmonious and sustainable future? How might we encourage the revival of the true archetype of the Warrior? Chapter Twelve of my book discusses “rituals of conflict”:

What if conflict itself had a completely different function from defending against, converting or eliminating the Other? Tribal people once believed that it existed to bring people together. We see vestiges of this in the Gaelic language. One cannot say, “I am angry at you,” but only, “There is anger between us.” This wisdom is present in the word competition (communally petitioning the gods). Engagement can refer either to martial or to marital affairs. Animosity, with its connections to animal, animate, animation andanima, derives from the Latin for “breath of life.” If we follow animosity to its archetypal source, we find the one breath we all share.

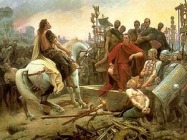

Greek myth provides a surprising image in the war god, Ares. Homer calls him “killer of men,” and he is “most hateful” To Zeus. But the Greeks saw him as an immortal god; so to us he is an image of the divine, and thus of the psyche.

This tells us first that Greek culture understood that martial values are fundamentally human, not to be demonized and certainly not to be ignored. Second, consider what it implies that Ares was taught to dance before he was taught the arts of war.

Third, he was Aphrodite’s lover. This most masculine god and this most feminine goddess birthed a daughter known as Harmonia (Harmony). Thus in pagan thinking the war god had a “harmonious” relationship with the feminine that balanced his destructiveness. There is sublime beauty in war, wrote Hillman, and there is conflict in love. Harmonia is the product of the Warrior in a balanced relationship with its complementary archetype, the Lover. Love and war beget harmony, as Psyche and Eros beget their daughter Voluptos, or voluptuousness.

Soldiers entering battle invoked Ares, asking for strength and courage. But they also called upon him to prevent unavoidable conflict from degenerating into uncontrollable violence, as in this 7th-century B.C.E. hymn:

Hear me, helper of mankind, dispenser of youth’s sweet courage, beam down…your gentle light on our lives…diminish that deceptive rush of my spirit, and restrain that shrill voice in my heart that provokes me to enter the chilling din of battle…let me linger in the safe laws of peace…

This poetry invites us to imagine a consciousness that loves conflict as a form of relationship, seeking restoration of harmony rather than domination. “Who would have imagined,” wrote Hillman, “that restraint is what Ares offers?”

An initiated warrior exhausts non-violent forms of persuasion (the realms of Athena and Hermes) before resorting to the most minimal level of violence. This is standard hero ideology, of course (the American Hero never strikes the first blow).

But here is the difference: the archetypal warrior sees violence as the failure of symbolic conflict. If he is forced into combat, he goes sadly. If he survives and returns, he grieves for all the dead, not just his compatriots, because he knows that his enemy was a part of himself. Even so, he may require deep and protracted immersion in the feminine waters of atonement before returning to normal life.

In primitive societies when violence ended, much ritual activity was intended to expiate guilt, including various kinds of ritual penance after killing. Often the returning warrior was considered sacredly polluted and had to undergo additional purification rituals. A Pima warrior withdrew from battle the moment he killed his opponent to begin his rites of purification. Any Papago man who had killed an enemy underwent a difficult, sixteen-day ordeal of purification before being readmitted to society.

Mythic Irish warriors had to be purified of their battle frenzy. After a great battle Cuchulain was still red-hot with war fury and remained extremely dangerous to his own people. The women solved the crisis by marching out naked to greet him. When the sight momentarily stunned him, men grabbed him and plunged him into a vat of icy water. His heat caused it – and a second vat – to evaporate and explode into steam. Only on the third dunking did he cool down enough; the city was saved.

The archetypal warrior stands vigilant, aware of his own dark potential and watching for external danger. In serving the Divine King of the psyche, he is charged with protecting boundaries. This doesn’t imply rigid armoring. He determines which outside elements to welcome and which are dangerous.

An example from biology is the immune system. The skin and lining of the small intestine are semi-permeable membranes that know what to allow inside (such as air and nutrients) and what to keep out (including microbes and toxins). When intruders cross the boundaries, certain white blood cells sound the alarm, others neutralize the invaders and still others curtail the immune response when the danger is over. Then the body creates anti-bodies to remember – memorialize (!) – the event and protect against future ones. The system discriminates between the two aspects of the Greek word xenos – stranger and guest. Similarly, in Irish myth the Fianna warriors  guarded the borders of the realm and asked all strangers: “Would you like a poem or a sword?”

guarded the borders of the realm and asked all strangers: “Would you like a poem or a sword?”

Ares loves conflict, but he is first and foremost a protector. And remember, he comes from the Pagan world, not the Judeo-Christian tradition of the renunciate warrior-monk. He retains his amorous relationship to Aphrodite and has many consorts and children. He is comfortable in relationship.

But Christianity, despite its historic dynamism and belligerence, cast him out. Like Dionysus, he finds expression only in images of the Other. So from the pagan perspective, just as Aphrodite’s exile leads to pornography, the absence of the war god causes literal violence that might otherwise be expressed symbolically.

Why, in the most competitive society in history, do “proper,” middle-class people avoid actual confrontation, restricting it to spectator sports? Perhaps we intuitively know that normal social interactions cannot contain conflict and prevent it from turning into literal violence; it simply isn’t safe. Our myth of redemption through violence polarizes us into one of the two most easily assumed stances: the path of denial and/or retreat, or the path of extermination. We inevitably resort to either fight or flight. And if we choose the former, we reflexively evoke our long heritage of total warfare, as we evolved it on the frontier.

Indigenous people understood that ritual provides a third alternative: staying in relationship without being violent. It requires, however, that participants acknowledge the reality of the Other. Traditional West African Dagara married couples engage in conflict rituals every five days. Certain that there will be no physical violence, each person simultaneously vents all accumulated emotions. If necessary, the entire village witnesses and affirms this ritual. Long experience has shown them that conflict causes damage to the entire community if it is removed from a bounded ritual container and brought out into the profane openness of daily life.

A second example is the kecak dance performances of Bali that convert aggression into art. The entire male population of a village (including boys) may enact battle scenes from the Hindu epics, with neither physical harm nor easy resolution of light over dark.

Another is the bertsolariak, the Basque poetry competitions, in which each participant improvises in accordance with a given meter, taking his cue from his rival’s poem.

Urban African-American culture abounds in the ritualized conversion of aggression into creativity. Examples include break dancing, poetry slams and “the dozens,” verbal jousting in which antagonists poetically insult each other’s mothers. Mythologist Lewis Hyde writes that the loser is “the player who breaks the form and starts a physical fight…who chooses a single side of the contradiction” between attachment and non-attachment to mother. To become a winner at this game (and remain non-violent), one learns to artfully hold the tension of the opposites.

Aphrodite’s sensual fury, said Hillman, is hardly different from that of Ares. In their union of sames rather than of opposites, passionate aesthetic engagement can restrain violence.Long-term discipline of an art – any art – tames hasty emotional expression and the urge for vengeance, but not its passion. Violence is beyond reason; what counters it must be equally unreasonable. “Imagine a civilization,” mused Hillman, “whose first line of defense is each citizen’s aesthetic investment in some cultural form.”

Mythopoetic men’s conferences have evolved effective conflict rituals that allow men to engage with each other on subjects as frightening as race and sex without either leaving or getting violent. In this context, safety means feeling secure enough within the ritual container to take risks. If men remain in this heat of confrontation long enough, they may get past anger to the underlying grief, to suffer together and to cleanse their souls.

Suffering together: Joshua Chamberlain was a general in the Union Army who recorded the awesome spectacle of Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9th, 1865:

Before us in proud humiliation stood…men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve…thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond…On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer…but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!…How could we help falling on our knees, all of us together, and praying God to pity and forgive us all!

The same principle holds for both individuals and large groups. Tragic Drama could be the model for future conflict rituals, which might enact our greatest moral conflicts before the citizens and challenge them to hold the tension of the opposites without succumbing to the temptation of quick resolution. Such rituals could lead to a long-term reframing of the meaning of the hero/warrior. We might learn to value this archetype’s protective and healing capacity, including the power of non-violence. Questioning the myth of violent redemption would lead to considering that initiated masculinity has a great variety of expressions. Women might acknowledge that patriarchy is caused not by men but by the lack of initiated men. The roles of the military and the police could shift from controlling the Other to – artfully – protecting the borders of the realm. The entire military could become the Coast Guard, real Homeland Security.

Pentheus, no longer fearing his dark mirror-opposite, no longer needing to vent his self-hatred and his grief for never having been initiated, might just invite Dionysus into the city for a competition of dance and poetry, fueled by the deep wine of the Soul.

We conclude by returning to the question of the Apocalypse, so ardently desired by fundamentalist Christians, drunks, suicides and warmongers. But we recall that the word means “to lift the veil.” No one needs to die (or kill) to be reborn; one only needs to wake up, to see and to acknowledge what D. H. Lawrence saw:

…only time can help

and patience, and a certain difficult repentance

long difficult repentance, realization of life’s mistake, and the freeing oneself

from the endless repetition of the mistake

which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify.

There is yet another meaning to “endings.” Seen from the detached perspective of the mystic, from the inspired eye of the poet and even from the cyclic movements of our lungs, each moment expresses both birth and death, each of which is an essential aspect of life…breathe out the end of time, breathe in rebirth. Start again, continue. As Victory Lee Schouten writes: Waking up groggy is still waking up.