Part Four

Myth is conveyed – and consumed – in narratives and images. So it is important to understand our most fundamental mythic image. The American obsession with individualism has been built up and buttressed by three centuries of stories, repeated in thousands of variations, of the lone, violent hero.

All societies evolved versions of Joseph Campbell’s classic “monomyth” — except America. Whereas the classic hero is born in community, hears a call, ventures forth on his journey and returns sadder but wiser, the American hero comes from elsewhere, entering the community only to defend it from malevolent attacks. He is without flaw but also without depth. He is not re-integrated into society. Not knowing his own darkness, he cannot symbolize genuine renewal.

When confronted with the villain (his mirror-opposite), he never strikes first because, above all, he embodies the Puritan quality of self-control. This is what proves his superior character. And since his adversaries lack self-control, they embody the Dionysian Other. He is individualistic, lonely, extraordinarily powerful, selfless – and, like the Christ he is modeled upon, almost totally sexless. Classic heroes often wed beautiful maidens and produce many children. But the American hero (with few exceptions such as James Bond and comic antiheroes) doesn’t get – or even want – the girl.

Consider John Wayne in Sands of Iwo Jima, Red River, The Searchers, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon and The Horse Soldiers. In each of these films he portrays widowed, divorced or uninvolved loners. They symbolize the man who has failed – or never attempted – the initiatory confrontation with the feminine depths of his soul. He carries with him the myth of violent redemption.

Am I exaggerating? How common is this unattached American hero? Consider some others: Hawkeye, the Virginian, Josey Wales, Paladin, Sam Spade, Nick Danger, Mike Hammer, Phillip Marlowe, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Dirty Harry,  John Shaft, Indiana Jones, Robert Langdon, Mr. Spock, Rambo, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Yoda, the Man With No Name, the Hobbits, Gandalf, Mad Max, Superman, Green Lantern, Green Hornet, Spiderman, the Hulk, Iron Man, Human Torch, The Flash, Dr. Strange, Hellboy, Nick Fury, Swamp Thing, Aquaman, Daredevil, Lone Wolf McQuade, Sargent Rock, Braveheart, Conan the Barbarian, Jack Sparrow, Captains Kirk, Picard, Atom, Nemo, Phillips, Marvel and America, as well as the heroes of Death Wish, The Magnificent Seven, The Dirty Dozen, Pale Rider, Unforgiven, Under Siege, Lethal Weapon, Blade, Casablanca, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, No Country for Old Men, Gran Torino, Walking Tall, Delta Force, Missing In Action, Avenger, Extreme Justice, The Equalizer, Terminator, The Exterminator, Rawhide, The Rifleman, Million Dollar Baby, Open Range, The Exorcist and countless other movies, novels and comic strips.

John Shaft, Indiana Jones, Robert Langdon, Mr. Spock, Rambo, Obi-Wan Kenobi, Yoda, the Man With No Name, the Hobbits, Gandalf, Mad Max, Superman, Green Lantern, Green Hornet, Spiderman, the Hulk, Iron Man, Human Torch, The Flash, Dr. Strange, Hellboy, Nick Fury, Swamp Thing, Aquaman, Daredevil, Lone Wolf McQuade, Sargent Rock, Braveheart, Conan the Barbarian, Jack Sparrow, Captains Kirk, Picard, Atom, Nemo, Phillips, Marvel and America, as well as the heroes of Death Wish, The Magnificent Seven, The Dirty Dozen, Pale Rider, Unforgiven, Under Siege, Lethal Weapon, Blade, Casablanca, One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, No Country for Old Men, Gran Torino, Walking Tall, Delta Force, Missing In Action, Avenger, Extreme Justice, The Equalizer, Terminator, The Exterminator, Rawhide, The Rifleman, Million Dollar Baby, Open Range, The Exorcist and countless other movies, novels and comic strips.

All are either single, divorced or (especially in Wayne’s films) widowers. Robert Jewett and John Lawrence write, “The purity of his motivations ensures moral infallibility,” but denies both the tragic complexity of the real world as well as the possibility of healing through merging with and incorporating the values of the Other.

In this mythology, women are merely excuses for the hero’s quest. I googled “prominent Libertarians” and discovered 17 women out of 194 (about 9%). Even the Senate has a higher percentage of women (23%). Again: the Libertarian’s allegiance, if he is honest (and he is usually a he), is to himself, whether he claims to be part of a family, a relationship, a business or a military unit.

The classic hero endures the initiatory torments in order to suffer into knowledge and renew the world. In this pagan and tragic vision, something must die for new life to grow. But the American hero cares only to redeem (“buy back”) others. Born in monotheism, he saves Eden by combining elements of the sacrificial Christ who dies for the sins of the world and his zealous, omnipotent father. The community begins and ends in innocence. And the Hero – absolutely unique in all the world’s mythologies – remains outside of that community.

Only in our salvation obsessed culture and the places our movies go does he appear. Then, he changes the lives of others without transforming them. This redemption hero has inherited an immensely long process of abstraction, alienation and splitting of the western psyche. He exemplifies that peculiar process upon which our civilization rests: dissociation. He is disconnected from both the feminine and the Other (psychologically, his own unacknowledged darkness), whom he has demonized into his mirror opposite, the irredeemably evil. Since he never laments the furious violence employed in destroying such evil, he reinforces our characteristic American denial of death.

Our monotheistic legacy of dissociation and our sense that we individuate by separating ourselves from the tangles of relationship and community merged long ago with the Puritan’s profound contempt for the poor. Together, they inform both the libertarian’s disinterest in social responsibility as well as his stunning ignorance of how centralized government built up his white privilege (oh, did I mention that there were few people of color in that list of prominent libertarians?)

The Hero’s appeal lies deep below rational thinking. He requires no nurturance, doesn’t grow in wisdom, creates nothing, and teaches only violent resolution of disputes. The regular repetition of his stories in the mass media clearly has a modeling effect on millions of adolescent males in each new generation. Defending democracy through fascist means, he renounces citizenship. He offers, writes Jewett and Lawrence, vigilantism without lawlessness, sexual repression without resultant perversion, and moral infallibility without intellect.

Unlike the universal hero who lifts the veil between the worlds to discover eternal values, the redemption hero pulls the veil back down, confirms our innocence, and puts everyone back to sleep.

Part Five

The Paradox of the Outsider

The redemption hero, like Christ, leaves once his work is done. He must leave; he came from somewhere else, and he must return. It should be clear by now how this mythology has had a very practical effect on the American family, especially on patterns of fathering. It is a very simple step from identifying (consciously or not) as a libertarian to minimizing and eventually denying one’s responsibility to the children of the poor, and eventually to one’s own children.

And it’s another series of simple and logical steps from choosing that libertarian identity to asserting one’s freedom from all duties to the community and government in any of its forms, to the position of rebel, and then on to the claim that law itself has no intrinsic hold on one, and then to the eventual assertion that one has the right to do anything at all, from child molestation to mass murder. One then finds oneself – proudly – in the position of the Other.

As I have suggested, innocent Eden is defined by the existence of the Other – the external Other of terrorism, and the internal Other of race. The Other is the outsider. Or: evil comes from outside. But so does redemption.

Riding off into the sunset, writes James Robertson, “…the cowboy hero never integrated himself with his society.” But he has quite a bit in common with his villainous adversary. Each rejects conventional authority, each despises democracy and, although they serve opposing ends (the classic pair is Ethan Edwards and Scar in The Searchers), their methods are similar.

The hero often becomes an outlaw (think Rambo) to defeat evil, because legitimate, democratic means are ineffective. Richard Slotkin writes that as early as the 1820s, the standard frontier hero of literature rescued captives by fighting the Indian “in his own manner, becoming in the process a reflection or a double of his dark opponent.”

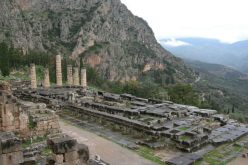

Eventually, the dual relationship in the mirror shatters and the villain must die, frequently in a duel. The one who can control his impulses defeats the one who cannot. In mythic terms, Apollo defeats Dionysus. (The Greeks, however, knew better. In myth, the hyper-rational god Apollo willingly left his shrine at Delphi for three months every year, so that his irrational, mad half-brother Dionysus could move in.)

Yet because he takes whatever he wants, has no responsibilities and transgresses all moral codes, the villain is exciting, and frankly attractive. Americans admire outlaws. Newspapers described an 1872 hold-up by Jesse James as “so diabolically daring and so utterly in contempt of fear that we are bound to admire it and revere its perpetrators.” For a time, this was a regular theme in cinema: in 1931 alone, Hollywood produced over fifty gangster movies in which the bad guys get away without being punished. It was said that when Al Capone took his seat at ballparks, people applauded. The Godfather is a regular candidate for the Great American Novel. In the era of capitalism’s greatest profits, millions identified with the criminal families depicted in The Sopranos and Growing Up Gotti.

The policeman and the criminal express contradictory impulses within American character. Puritan zeal for order clashes with its equal, the frenzied quest for wealth. Robert Warshow writes that the gangster is “what we want to be and what we are afraid we may become.” For more on this topic, see George De Stefano’s An Offer We Can’t Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of America.

Both share still another characteristic: the villain’s rage is a natural component of his pleasure in violating all boundaries, while the hero is also full of rage. Only by killing the villain, writes sociologist James Gibson, can the hero “release the rage accumulated from a life of emotional self-denial.”

Like the villain, the libertarian also loathes governmental limits on his quest for wealth. And, in rejecting religious constraints as well, he believes that he has the best of both worlds.

But what about the libertarian’s vaunted opposition to the military and its sworn duty to enact the extremes of empire? Looking back at that list of prominent, self-described “libertarians,” we notice plenty of men (Bob Barr, Gary Johnson, the Koch Brothers, Rupert Murdoch, Rand Paul, Paul Singer, Peter Thiel, Bill Weld, etc) who have displayed little concern with this question. Granted, they are all obvious hypocrites, devoted to conning the rubes in the service of Wall Street. But perhaps we can judge the ideological tree by its strange fruit.

Though the hero rejects society’s rules, he is hardly alone; the desperado and the hedge fund CEO, whom we can’t resist admiring, join him, along with all the Others who have been pushed beyond the walls or down into the underworld (a term which was first used to describe organized crime in the 1920s). The mythic roots of crime in America, organized or not, are different from those in other countries. As I write in Chapter Nine of my book,

…when our assumptions of social mobility are revealed as fiction, the hero encounters his opposite – the victim – within himself, and we become what we really are (except for Nazi Germany), the most violent people in history. American crime is a natural by-product of our values, an alternative means of social mobility in a society where “anything goes” in the pursuit of success. “America,” says mythologist Glen Slater, “has little imagination for loss and failure. It only knows how to move forward.” We go ballistic when we can only imagine moving forward and that movement is blocked. Then guns become the purest expression of controlling one’s fate. As such, they are “the dark epitome of the self-made way of life.” We as a people may well dream bigger dreams than other peoples. With great possibilities, however, come great risks. Gaps between aspiration and reality – the lost dream – are also far higher here than anywhere else. When we don’t meet our expectations of success, when that gap gets too wide, violence often becomes the only option, the expression of a fantasy of ultimate individualism and control. In this sense, the Mafia is more American then Sicilian, and the lone, mass killer (almost all of whom have been white, middle class men with no criminal background) is an expression of social mobility gone bad.

Again, we must note that, as Lewis Lapham argues, “…material objects serve as testimonials to the desired states of immateriality – not what the money buys but what the money says about our…standing in the company of the saved.” These are the logical extremes to which libertarianism – either anarchy or a police state – would invite us, and the American psyche is too willing to follow.

The Race Card

Exploring further into American myth, we inevitably confront the deeply racist nature of our society. American innocence is built upon fear of the “Other” – Indians, Mexicans, Asians, Communists and terrorists, but always and primarily, African-Americans. The fact that, in our time, politicians and pundits regularly admonish progressives for playing the “race card” indicates the terrifying truth that, to a great extent, the subject remains taboo. And anthropology teaches us that what is taboo is sacred. Like the Hebrew god Jehovah, it is too holy to be named.

White supremacy (as fear, as white privilege and as the underpinning of our entire economy) is the great unspoken – and therefore sacred – basis of our very identity as Americans. White Americans know who they are because they are not the Other. In a culture built upon repression of the instincts, delayed gratification and a severe mind/body split, we have, for three centuries, defined the Other as those who cannot or will not restrain their impulses. And we continue to project those qualities upon Black and Brown people.

In this American context, the fear of government intrusion upon the individual too often serves as a euphemism for the concern that one’s personally hard-earned assets (despite the legacy of white privilege and corporate welfare) might be taken away and given to people who are too lazy to work for themselves.

These attitudes are essentially religious, even if articulated in secular terms. Underneath the clichés lies our still-powerful Puritan contempt for the poor. Surveys show that the majority of Americans deeply believe that losers are bad and morally corrupt. To fail economically is not simple failure but – in America – moral failure. And neither American myth nor American politics distinguishes between race and class.

Thus, the libertarian has a deeply religious argument for keeping all of his money. He rationalizes his greed with a secularized argument that subsidizing the poor will only encourage them in their laziness. If they suffer it is their own fault. That a Black child should be undernourished because her parents cannot find employment is irrelevant.

These themes have been played out with increasing effect since the end of the 1960s, when conservatives, far more literate in American myth than liberals, began to masquerade as rebels against the establishment. Their narrative took full advantage of the fact that American myth offers only these alternatives to the hero – the victim and the villain. They emphasized “values” over “interests,” redefining class war, again, in racial and cultural rather than economic terms. Although this fable was aimed at traditional, conservative men, undoubtedly many libertarians soaked up their own rhetoric, perceiving themselves as victims of greedy, inefficient, inappropriately compassionate bureaucrats.

Ronald Reagan’s genius was to articulate hate within the wider myth of American inclusiveness, appealing to white males by evoking both ends of the mythic spectrum. He told them, writes Robert Bellah, that they could have it both ways: “You can…get rich, and you can also have the traditional values…have everything and not pay any price for it…” They could be both Puritans and Opportunists. Reagan’s backlash against the perceived excesses of the 1960s resolved whites of responsibility and renewed their sense of innocence and privilege,

Ever since, Middle America has supported leaders whose policies continue to wreck both the affluence and the family values that they hold so dear. Indeed, Reagan managed the greatest shift of wealth in history, turning the world’s most affluent nation into its greatest debtor nation.

He presided over a time during which, in a thousand subtle ways, government announced that the 300-year old American social contract, the balance between freedom (the rights of the individual) and equality (the community’s needs) was broken. A major theme of his revolution was a return to small town values. But its subtext was greed, racism, contempt for the poor and narcissistic individualism. Reagan gave white men permission to circle the wagons, retreat within the pale (pale skin) and reduce the polis to a size that excluded most of its inhabitants, and all current Republican leaders learned the lesson well.

To the ancient Athenians, someone who wouldn’t participate in the welfare of the poliswas an idiota. Reagan gave Americans permission to be idiots. Now they have elected one, or at least a man who plays one on TV.

Ironically, one could trace the recent roots of this socially libertarian yet fiscally conservative fashion to the radical individualism of the sixties.  Fritz Perls, a founder of the Human Potential Movement, had coined the ubiquitous statement of detachment from the polis seen on every t-shirt in those days, sometimes known as the “Gestalt Prayer”:

Fritz Perls, a founder of the Human Potential Movement, had coined the ubiquitous statement of detachment from the polis seen on every t-shirt in those days, sometimes known as the “Gestalt Prayer”:

I do my thing, and you do your thing. I am not in this world to live up to your expectations…you are not in this world to live up to mine…if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful. If not, it can’t be helped.

Carl Cederström, in The Happiness Fantasy, takes this idea further, arguing that counterculture values— liberation, freedom, and authenticity — were co-opted by corporations and advertisers, who used them to perpetuate a culture of consumption:

Happiness became increasingly about personal liberation and pursuing an authentic life. So happiness is seen as a uniquely individualist pursuit — it’s all about inner freedom and inner development…the advertising industry changed their tactics and vocabulary and effectively co-opted these countercultural trends. At the same time…Reagan and Margaret Thatcher…were advancing a very individualistic notion of happiness and consumerism, and all of this together had a huge impact on our culture and politics…these values have been co-opted and transformed and used to normalize a deeply unjust and undesirable situation.

I think that ends where we are now, with a culture of extreme individualism and extreme competitiveness and extreme isolation…a situation where people feel constantly anxious, alienated, and where bonds between people are being broken down, and any sense of solidarity is being crushed.

Meanwhile, an extremely well-funded conservative media barrage was taking advantage of the old tradition of anti-intellectualism. “Elite” now meant stuffy, superior, arrogant liberals who trivialized the concerns of ordinary people. Many retreated into religious fundamentalism. White males, oblivious to their privilege, identified as victims – not of the rich, but of the minorities who were competing with them, the women claiming equality with them, the gays who publicly questioned the value of their masculinity and the intellectuals who appeared to be telling them how to live. The investment paid off; by 2000, only a fifth of Americans would describe themselves as liberal, even though a clear majority have always held liberal values.

For others, radical individualism and the culture of consumption were replacing older forms of group solidarity. Indeed, the U.S. Libertarian Party had run its first presidential candidate in 1972, just as the reaction against the 1960s was gaining steam. Eventually, the streams ran together and produced some crazy combinations, such as the above-mentioned “libertarian” Rand Paul who opposes gun control but would ban abortion and same-sex marriage. And all, whether religious extremists or free-market true believers, would find easy targets to blame.

One of the primary objectives of the corporate media and our other mythic instructors is to distract Americans from identifying both the true spiritual and economic sources of their pain, and the actual opportunities for addressing them. Therefore, the victim who cannot be a hero will search for villains or scapegoats. This is one way to understand right-wing activism: deeply committed, emotionally intense, sustained effort under the identification as victim, their targets being precisely those categories (race and gender) whom they have been educated to perceive as questioning or contesting that privilege.

Hence, we have, and certainly not for the first time in our history, groups of relatively well-off people who actually perceive themselves to be the victims of people who have far less than they do. And not just the relatively well-off. For example, I used to know a 50-year-old man who did odd jobs for me. He lived with his mother and was usually broke. Once, he declared that things were going badly for middle-class people like him and me. Middle-class? He was a good man, but the only way he could identify as middle-class was to remain blind to his own white privilege (and the welfare he was receiving).

This is the broader context behind Libertarianism. For at least the last thirty years, millions of Americans have described themselves as “liberal on social issues but fiscally responsible.” Factoring out the complex issues of tax policy, immigration, jobs, white-collar crime and the military, this translates as increasingly broad support for abortion rights, gay marriage, environmental protection, and de-criminalization of drugs on the one hand – and drastically lower taxes on the other. With most Americans wanting to have their cake (freedom plus government services) without having to pay for it, it hardly seems surprising that a minority would be attracted to Libertarianism, which is, after all, merely an extreme expression of that which makes us all – exceptionally – Americans.

Part Six

Coda: The Myth of Growth

The goal of Survivor, now in its 37th season, is to manipulate and scheme against other participants until only one winner is left. Its longevity exemplifies the American dogma of unlimited economic growth, which teaches that all must be free to achieve their potential through independent, meritorious (and if not, then creatively dishonest) action.  Its relentless logic, however, turns nature into a resource and objectifies humans into individual rather than social animals. All motivation becomes self-interest, and – this is critical – no winners can exist without losers to compare themselves to.

Its relentless logic, however, turns nature into a resource and objectifies humans into individual rather than social animals. All motivation becomes self-interest, and – this is critical – no winners can exist without losers to compare themselves to.

For libertarians, simplistic faith in “the market” mirrors the fundamentalist’s faith in scriptural authority. In this story, the greatest sins are not violence but personal laziness (the crime of the Puritan) and social intrusion (the nightmare of the Opportunist.) Activist government, by taxing the privileged to sustain the needy, calls this faith into question: if everyone, even the poor, is entitled to basic human rights and dignity, then no one is automatically among the elect. If even the children of the homeless deserve care, nutrition and decent schooling, then students at the Georgetown Preparatory School are really not that special after all.

But we are talking about a belief system. Libertarianism is merely the extreme version of the creed of the individual who should be free to build, buy, steal or waste whatever he wants. True adherents of this theology then argue against all evidence that the “rising boat” of generalized wealth may possibly lift the less deserving along with the rich. On the other hand, as J.M. Keynes argued, capitalism is the extraordinary belief that the nastiest of men, for the nastiest of reasons, will somehow work for everyone’s benefit. And such beliefs inevitably lead to a world of euphemisms, such as terms like “productivity” hiding the truth of “increased unemployment.”

A hundred and fifty years before recent Supreme Court decisions, the myth of growth enshrined the idea that abstract concepts devoted solely to accumulating capital – corporations – have all the rights of persons, plus limited liability and the freedom to externalize costs. Who are the gods of this theology? Corporations are immortal. They can reside in many places simultaneously, transform themselves at will and do virtually whatever they choose, but they can’t be punished (or in practical terms, taxed).

Corporate headquarters, like medieval religious shrines, are housed in America’s tallest buildings. Americans express our aspiration to greatness through the metaphors of size, speed, height, expansion, acceleration and constant action. Our uniquely American term “manifest destiny” has always implied both territorial expansion and cultural influence. We outrun the competition and climb out of ignorance, up the rungs of the ladder of evolution. Great music “uplifts” us. The greater grows by “rising” out of the lesser. Many books on American history utilize this phallic language: The Rise of American Civilization, The Rise of the Common Man and The Rise of the City. Even in slang, both intoxication and euphoria are “highs,” psychologically depressed individuals are “down” and bad news is a “downer.”

Counter-arguments produce anxiety, because we perceive them as attacks upon the faith itself. If one grows from wet/dark/feminine to dry/light/masculine, then appeals to sustainability become entwined with threats to masculinity itself. Male identity converges with the imperative to grow; everything is bound up in “potential” and “potency.” Bigger is not simply better, but the only alternative to “smaller,” as “hero” is to “loser.” Jimmy Carter suggested mild limits to growth and was destroyed politically for the attempt. Studying his fate, Reagan, Clinton, both Bushes, Obama and Trump have promised to limits government, even as they increased its size.

The belief that the imperative of growth (as quarterly profits) trumps life itself underlies all corporate and most government policies and leads to the conservative mental gyrations of attacking big government while praising its responsibility to support the private sector through subsidies, infrastructure and military intervention – all forms of externalizing costs. The result is an economy, wrote James Hillman, that is “…the God we nourish with actual human blood.”

The holy text of this theology, the Gross Domestic Product, symbolizes the pathology of growth in four ways. First, it counts all economic activity as valuable, such as the $20 billion we annually spend on divorce lawyers, or cleaning up after a hurricane, and never distinguishes between textbooks and porn magazines. It includes every possible aspect of a person’s death from lung cancer – medical, hospital, pharmaceutical, legal and funereal – as well as the land purchasing, growing, transporting, packaging, marketing and eventual disposal of tobacco products, and the defense of their producers from class-action lawsuits. Increased gas expenditures add to the GDP without a corresponding subtraction for the toll fossil fuels take on the thermostatic and buffering functions of the atmosphere. Luxury buying by the rich covers up a lack of necessary buying by the poor.

So the GDP actually disguises suffering. The ultimate example is war: exceptionally costly, energy-intensive, requiring lengthy cleanup and long-term medical bills. By adding to the GDP, however, it builds an artificial sense of economic health. And for the last sixty years, preparation for war (the Defense Department and all related expenditures in the Energy Department and Homeland Security as well as veteran’s benefits and proportional percentages of interest payments of the national debt) has accounted for well over half of the nation’s annual budgets and similar percentages of the GDP.

Second, judging profitability on quarterly stock reports rather than on long-term sustainability leads to the maximization of short-term strategies (such as investing in the SUV rather than in energy-efficient cars)  at the cost of long-term losses. It also leads to outright, deliberate lying about those long-term effects, from “healthy” cigarettes and mercury-laden dental fillings to death-trap cars and global warming.

at the cost of long-term losses. It also leads to outright, deliberate lying about those long-term effects, from “healthy” cigarettes and mercury-laden dental fillings to death-trap cars and global warming.

Third, the GDP is so wildly inaccurate – because it completely ignores the massive underground economy of drugs, prostitution, gambling and crime (blue- or white-collar) – that it has nothing really practical to indicate about the economy anyway.

Fourth, it discounts and ignores the actual, natural economy. As Robert F. Kennedy said, it “measures everything…except for that which makes life worthwhile.” Most crucial life-supporting functions take place not through the market, but through social processes and voluntary activities (families and churches) or through completely natural processes (the cooling and cleansing functions of trees, etc). None register in the GDP until something damages them and people have to buy substitutes in the market. In this mad calculus, fuel conservation, stable marriages, children who exercise and eat healthy foods and world peace are threats to the economy.

Many “progressives” are also unaware of the pervasiveness of this story. Clearly, recession hurts the poor most. But we reveal ignorance of our myths when we demand larger shares of an ever-expanding economic pie, or lament “underdevelopment” in other nations. Growth, whether inequitable or sustainable, leads inevitably to the terrifying vision of seven billion people each driving their own SUV.

Eastern wisdom teaches that we can never satisfy the soul’s hunger with material food alone. Yet self-improvement and growth are such bedrock American values that, by the 1970s, they were, once again, models for the spiritual life. Hillman argued that the first assumption of the “therapeutic culture” is that emotional maturity entails a progressive differentiation of self from others, especially family. American psychology mirrors its economics: the heroic, isolated ego in a hostile world.

For a significant segment of the population, “inner growth” replaced the old ideal of the democratic citizen. Well-meaning people, more American than they knew, spoke of what they could get from life, rather than, to paraphrase John F. Kennedy, what they could give to it. Spiritual growth became another version of the pursuit of happiness, now defined by “heightened awareness” and “peak” experiences. “Feeling good,” wrote psychologist Lesley Hazleton, became “no longer simply a right, but a social and personal duty.” And the economy offered the material symbols that gave evidence – proof, in Puritan terms – of spiritual “growth.”

This idea takes its energy from two older ones: life-long initiation, and biological maturation. But it has split off from the natural and indigenous worlds in its unexamined assumptions. All living things die and return to Earth, but a “growing” person, by definition, cannot. Initiation absolutely requires the death of something that has grown past its prime. And worse, since the myth of growth (material or spiritual) is essentially a personal story, it narcissistically assumes the unlimited objectification and exploitation of others for the ultimate aggrandizement of the Self.

Gary Snyder points out that we find unlimited growth in neither nature nor culture, but only in the cancer cell, which multiplies until it destroys its host. The miracle of reproduction serves death instead of life. Growth inevitably evokes its opposite. The body produces anti-bodies, which destroy the invasion of grandiosity. There is no more basic ecological rule. Natural growth only occurs within a broader cycle that also includes decay.

But when growth, potency, happiness, pressure to be in a good mood, to “have a nice day,” to be “high” are hopelessly intertwined with consumer goodies, not having them means a drop into shame and depression, from the Hero to the Victim. In the real world of limited resources, growth is a Ponzi scheme in which our great-grandchildren subsidize the childish and narcissistic fantasies of those who call themselves libertarians.