Part Six

A myth never says what to do; it points out where the difficulties will arise. – Ginette Paris

The past isn’t dead. It is not even past. – William Faulkner

At this point things get far more complicated, just as they do in the unconscious mind. Pelops and Hippodamia had many children, but his favorite was an illegitimate son, Chrysippus. Hippodamia convinced her own sons Atreus and Thyestes to murder him. Pelops banished them, and Hippodamia hanged herself. The exiled brothers went to Mycenae because an oracle had prophesied that its vacant throne would eventually belong to one of Pelops’ sons. There, the royal sibling rivalry commenced. Roberto Calasso writes:

Every story of two is always a story of three: two pairs of hands grab the same thing at the same time and tug in opposite directions.

Atreus, the eldest, claimed the throne. He married Aerope, who bore him two sons, Agamemnon and Meneleus (although some say the real father was her brother-in-law Thyestes). He vowed to sacrifice his best lamb to Artemis. However, when he discovered that there was a golden lamb in his flock, he decided to hide it from the goddess and gave it to Aerope for safekeeping.

But Aerope, who’d been sleeping with Thyestes, gave it to him instead. He then convinced Atreus to agree that whoever possessed this lamb should be king. Thyestes produced it and claimed the throne, agreeing to give the kingdom back to Atreus only if the sun should move backwards in the sky – a feat that Zeus, who favored Atreus, accomplished. Atreus retook the throne, banished Thyestes and might have been satisfied. However, having learned of the adultery, he devised an atrocious revenge. Now, writes Calasso,

…the conflict is raised to a higher power: it is the winner who wants to revenge himself on the loser, and…wants his revenge to outdo all others.

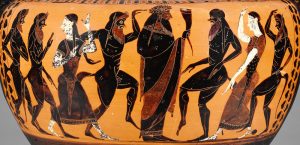

Atreus invited Thyestes to a banquet. Then he had his brother’s children (one of whom was named Tantulus) killed, dismembered and cooked, except for their hands and feet.  Thyestes unknowingly consumed their flesh. After taunting him with their hands and feet, Atreus again forced him into exile. Once again innocent children were eaten at a grizzly banquet.

Thyestes unknowingly consumed their flesh. After taunting him with their hands and feet, Atreus again forced him into exile. Once again innocent children were eaten at a grizzly banquet.

From this point on the vendetta between the two brothers loses all touch with psychology, becomes pure virtuosity…

Thyestes sought an even greater vengeance, one that would attack future generations. An oracle advised him to rape his own daughter, Pelopia, whose son would then kill Atreus. Some say that Thyestes, like Oedipus, didn’t know that she was his daughter. If he did know, then he was willing to ruin her just to get that revenge. In either case (just as with Oedipus), myth is concerned with action rather than with motivation. Psychology asks why it happened, but myth only tells what happened.

After giving birth to the boy, she abandoned him. Atreus murdered Aerope for her infidelity. Desiring a new wife, he married Pelopia, not knowing her parentage. A shepherd found the infant Aegisthus and gave him to Atreus, who raised him as his own son. Meanwhile, the region around Mycenae suffered a terrible drought, which would end, said an oracle, only if Thyestes returned. Atreus located his brother and brought him back to prison, where he ordered the boy to kill him. When Thyestes revealed himself to Aegisthus as his both his father and his grandfather, Pelopia killed herself. Instead of killing him, the boy killed Atreus, and Thyestes became king. But, writes Calasso,

…the grindstone that had accelerated during their feud would go on crushing bones, for one, two, three generations to come.

The Seventh Generation

Agamemnon and Menelaus escaped to Sparta, where King Tyndareus sheltered them and helped them return to overthrow Thyestes. Tyndareus offered his daughters Clytemnestra and Helen (half-sisters to Castor and Pollux, but that’s another story) to Agamemnon and Menelaus as wives. Menelaus became king of Sparta and Helen gave birth to Harmonia. Agamemnon ascended to the throne of Mycenae and Clytemnestra bore Orestes, Elektra, Iphigenia, Erigone and others. Some say that her first husband had been yet another Tantalus, grandson of the original Tantalus, and that Agamemnon had killed him.

We are familiar with the seventh generation from the stories of the Trojan War, which had its roots in the wedding of the mortal Peleus and the sea nymph Thetis. Previously, Zeus and Poseidon had courted her, but they withdrew when they heard that her son would be more famous than the father (the actual son would be Achilles). In safely marrying her off to Peleus, Zeus planned a grand wedding. It turned out to be the last one that mortals and immortals celebrated together. All the gods and goddesses were invited, with one exception – Eris (Discord), twin sister of Ares, another of Zeus’ rejected children. Why hadn’t they invited her? Ginette Paris writes:

A reality (marriage) that invites so many gods and goddess cannot be separated from its shadow…no powers exist without a dark side, and when they are denied, murderous feelings become murderous behaviors.

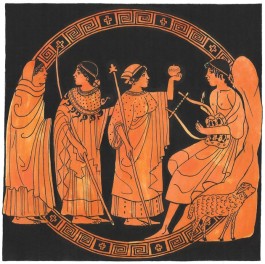

Enraged, Eris barged in anyway and rolled a golden apple marked “for the fairest” into the hall, quickly provoking an argument between Hera, Aphrodite and Athena.

They asked Zeus to judge between them, but he refused to get involved. He sent them to Mount lda, near Troy, telling them that Paris would be the judge.  This prince had been sent away because his father, King Priam, had heard yet another prophecy that Paris would someday be the ruin of his country. Each of the goddesses offered a bribe, but he preferred Aphrodite’s – the fairest woman in the world. In choosing her, he – and Troy – earned the enmity of the other two goddesses.

This prince had been sent away because his father, King Priam, had heard yet another prophecy that Paris would someday be the ruin of his country. Each of the goddesses offered a bribe, but he preferred Aphrodite’s – the fairest woman in the world. In choosing her, he – and Troy – earned the enmity of the other two goddesses.

That woman, of course, was Helen, another daughter of Zeus, who had seduced her mother, Leda, in the form of a swan. As we’ve seen, Leda’s husband Tyndareus gave Helen as wife to Menelaus. But before announcing his choice, Tyndareus made all the Greek princes promise to support Helen’s husband. Later, Aphrodite directed Paris to Sparta and Helen as his promised reward. When Paris and Helen eloped, all the Greek leaders were bound by their promise to help Menelaus get her back. They mobilized a thousand ships and an entire generation of young men, with Agamemnon as commander, all for the sake of one woman.

We may think of this “one woman” in at least three ways. Since possession of Helen symbolized regal sovereignty, she had to be recovered. But Menelaus, son of the cruel Atreus, had his own childhood wounds. In this age of recovery, we can see his willingness to risk his fortune, his life, and the lives of thousands of men to get her back as the essence of co-dependency. He sought the answer to his unmet infantile needs in a relationship with the Golden Woman. Or, from a Jungian perspective, he was seeking his anima, in a necessary journey of individuation.

But why the huge mobilization of all the “Argive host”?

Wasn’t Helen an idea, a belief system, an ideology? Both archetypal psychology and traditional indigenous wisdom see any ideology, religious or political, as an addiction. When carried to its extreme it becomes dogmatic fanaticism, an all-encompassing, paranoid world view which necessarily dehumanizes all non-believers. Fanaticism encloses us in a warm, comfortable womb of like-minded individuals and stimulates our participation in group action that (only) temporarily satisfies our need for ritual and community. In providing a superficial connection to others, it covers up our narcissistic wounds and cuts us off from true relationship.

In short, whether Helen was the unreachable object of an immature relationship, a Golden Anima figure or the spirit-crushing panacea of fanatic ideology, she represented a hiding place for the shame people receive from parents who couldn’t be what they needed when they needed it.

Part Seven

…we live in an age of Moms, for the culture is secular and the ordinary mortal must carry archetypal loads without help from the gods. The mothers must support our survival without support themselves, having to become like Goddesses, everything too much, and they sacrifice us to their frustration as we in turn…sacrifice our children to the same civilization. – James Hillman

I am pregnant with murder. The pains are coming faster now, and not all your anesthetics nor even my own screams can stop them. – Robin Morgan

The Eighth Generation

The curse appeared in the form of a tragic dilemma at the port of Aulis. The north wind blew continually, preventing the ships from embarking for Troy and provoking discontent among the troops. Agamemnon learned that he’d offended Artemis by killing one of her favorite animals. There was only one way to appease her and change the winds: his daughter Iphigenia must be sacrificed.

Making the fatal choice for fame and against family, he convinced Clytemnestra to send the girl, believing that she would be married to Achilles. Instead, the men murdered her at the ritual alter. The winds ceased and the fleet – stained by guilt – sailed for Troy. Jean Bolen comments:

They sacrifice the possibility of closeness to their children to their jobs, their roles. And they also sacrifice their own “inner child”, the playful, spontaneous, trusting, emotionally expressive part of themselves…Agamemnon was thus another father (like Abraham) who was rewarded by his willingness to kill his child…the father who violates the trust of a daughter and destroys her innocence, destroys a corresponding part of himself.

His reward did not last. During the years that Agamemnon was at Troy, Aegisthus returned and seduced Clytemnestra. They sent Orestes out of the country, neglected Electra and plotted against Agamemnon. When he returned, they killed him and his concubine Cassandra in the narrative we know best from the first play in Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, Agamemnon.

For lack of time, we limit our attention to three aspects of the play. The first is the repetition of the lament, Sing sorrow, sorrow: but good win out in the end…Justice so moves that those only learn who suffer, which sums up the necessity of grieving.

The second is how the citizens of Argos waited eagerly for news of the return of the king. Agamemnon was a narcissist and a war criminal and a terrible father. He’d been an Ouranos father to Orestes and Electra, by abandoning them to his heroic quests, and he’d been a Kronos to Iphigenia, literally killing her. But to his people, he represented the Sacred King, a figure that embodies order, fertility and blessing. The longing for the Return of the King is an archetypal theme that appears everywhere, especially in Hebrew and Christian mythology, with significant political implications in modern America.

Despite his personal failings, Agamemnon also represented an initiated, male to Orestes, who desired a positive connection with him in life or death. Joseph Campbell wrote:

The finding of the father has to do with finding your own character and destiny. There’s a notion that the character is inherited from the father, and the body and very often the mind from the mother. But it’s your character that is the mystery, and your character is your destiny. So it is the discovery of your destiny that is symbolized by the father quest.

Third, Clytemnestra had long nursed a mother’s fury for his crimes and, despite her royal privileges, carried the collective resentment of hundreds of generations of oppressed women. She was convinced that she was meant to be the agent of his fate and needed no prodding from any god: “We could not do otherwise than we did.”

Seven years later (in the second play, The Libation Bearers), Electra hated her mother and desired only revenge. She carried the set of emotional obsessions that Freud, searching for a parallel to the Oedipus Complex, would later term the “Electra Complex.”

Orestes secretly returned with his cousin Pylades, having been directed by Apollo to be the agent of vengeance – in contrast to Clytemnestra’s usurping of that role. If this tale were focusing on Electra alone, we might well see continuation of the violence into the next generation. But Orestes, faced with the terrible task of having to kill his mother to avenge his father, appealed to higher powers: Hermes, Zeus and especially Apollo:

For he charged me to win through this hazard, with divination of much, and speech articulate, the winters of disaster under the warm heart were I to fail against my father’s murderers; told me to cut them down in their own fashion, turn to the bull’s fury in the loss of my estates. He said that else I must myself pay penalty with my own life, and suffer much sad punishment…

We can think of Apollo as an inner voice that offers Orestes the means to attain initiation to a new life that will not be predetermined by his family history. He can connect to the king-father’s realm only through a brutal separation from the mother’s realm. The quest for the father, according to Campbell, “…begins not with any initiative of his own but with a call.”

Orestes heard that Clytemnestra had dreamed that she’d given birth to a snake which had torn her nipple and drawn blood along with milk:

…it fellows then, that as she nursed this hideous thing of prophecy, she must be cruelly murdered. I turn snake to kill her.

References to snakes, serpents and vipers appear continually in the trilogy, generally with negative connotations. But here the snake has a positive tone. Campbell wrote:

The wonderful ability of the serpent to slough its skin and so renew its youth has earned for it throughout the world the character of the master of the mystery of rebirth.

Bly adds: “Initiation asks the son to move his love energy away from the attractive mother to the relatively unattractive serpent father.”

Orestes and Pylades quickly killed Aegisthus, but when they came face to face with Clytemnestra, she warned:

Your mother’s curse, like dogs, will drag you down.

At the initiatory moment Orestes was immobilized by indecision. But Pylades reminded him:

What then becomes thereafter of the oracles declared by Loxias (Apollo) at Pytho? What of sworn oaths? Count all men hateful to you rather than the gods.

Orestes fulfilled Apollo’s command and murdered his mother as savagely as she’d killed his father.

But we have to ask, what (rather than whom) did he kill? When the father is absent, with no masculine energy in the household, the archetypal Great Mother can overlap with and get confused with the human mother in a boy’s mind. Jung wrote that the mother archetype can be “terrifying and inescapable like fate.” For men it becomes mixed with projections of the anima, and statements of men about the mother “are always emotionally prejudiced…showing ‘animosity.’” The bad mother in myth or the subconscious is a man’s mother complex: that flawed relationship with the feminine part of his own soul, which, as Robert Johnson wrote:

… would like to return to a dependency on his mother and be a child again…a man’s wish to fail, his defeatist capacity, his subterranean fascination with death or accident, his demand to be taken care of.

This symbolic, inner figure determines how a man sees all relationships. The real tragedy is that if he who cannot “kill” his mother complex, he may turn his depression or misdirected rage onto actual women, perpetuating the conditions of patriarchy. Such a man can’t experience initiatory transformation, can’t realize his purpose and can’t love a real woman, or anyone else. But he will force both nature and women to take the blame that might be better directed at his father.

Still, Clytemnestra’s rage speaks for all women throughout time. Who can blame women who strike back at abusive spouses? And yet her murder may well have served as a model for men to continue the abuse. We acknowledge the complexity of this issue, and we tread delicately.

But we miss a great opportunity when we take mythic images literally. These are symbolic murders that we perceive as literal only if we have lost the capacity for metaphorical thinking. Hillman wrote: “The way to ‘solve the mother complex’ would be not to cut from Mom, but to cut the antagonism that makes me heroic and her negative.”

And let’s be very clear about this once more: We are not blaming actual, living, human mothers here. If anyone is to blame it is patriarchy itself.

Orestes knew the consequences of his actions, and the appropriate human response:

I grieve for the thing done, the death, and all our race. I have won; but my victory is soiled and has no pride.

By the end, he was alone with the the horrible vision of the dog-faced Furies:

…they come like gorgons, they wear robes of black, and they are wreathed in a tangle of snakes. I can no longer stay…the bloodhounds of my mother’s hate. Ah, Lord Apollo, how they grow and multiply, repulsive for the blood drops of their dripping eyes…You cannot see them, but I see them. I am driven from this place…

The act of separation from the mother does not imply an instantaneous resolution, only the beginning of a long healing process. Orestes had to grieve the loss of both parents and a sister and also face intense guilt, symbolized by the Furies. Pursued by the hideous apparitions, he hoped to find sanctuary at Apollo’s shrine.

But we find the possibility of healing in the differences between Orestes’ actions and Clytemnestra’s. Each committed a horrible crime. The third part of the trilogy involves much legalistic hair-splitting over which crime is worse. But our interest lies in two other areas, motive and response. The difference in response is simple: Orestes lamented and Clytemnestra didn’t. Indeed, none of their ancestors but Niobe had grieved the consequences of their actions.

The difference in response is due to the difference in motive. Orestes acted because of a call from Apollo, whom he couldn’t refuse. She, on the other hand, acted without any call from a god, but purely out of her own rage and hatred. Her excuse had been that she’d been an agent of fate. In reality, she had usurped the role of the god. She was inflated, according to Edinger:

It is a state in which something small (the ego) has arrogated to itself the qualities of something larger (the Self) and hence is blown up beyond the limits of its proper size…We can identify a state of inflation whenever we see someone (including ourselves) living out an attribute of deity, i.e., whenever one is transcending proper human limits…The urge to vengeance is also identification with deity. At such times one might recall the injunction, “’Vengeance is mine,’ saith the Lord,” i.e., not yours. The whole body of Greek tragedy depicts the fatal consequences when man takes the vengeance of God into his own hands.

We act “shamelessly” (including rage, arrogance, criticism, perfectionism, patronizing and other modes) to deny the felt sense of toxic shame. In contrast, Bradshaw defined natural, “healthy” shame as:

…the emotion which gives us permission to be human…Our shame tells us we are not God. Healthy shame is the psychological foundation of humility. lt is the source of spirituality.

The Furies attacked Orestes and no one else in the long story. The implication is that he was the only person to allow them in. He chose to go down into grief. They didn’t attack Clytemnestra because she felt no remorse. She was shameless. Her story ended with her de-flation.

Orestes’ action, however, was justified by the call from Apollo. Edinger speaks of “necessary crimes” in dreams and mythology:

What is a crime at one stage of psychological development is lawful at another and one cannot reach a new stage…without daring to challenge the code of the old…Hence, every new step is experienced as a crime and is accompanied by guilt, because the old standards, the old way of being, have not yet been transcended…The acquisition of consciousness is a crime, an act of hybris against the powers-that-be; but it is a necessary crime, leading to a necessary alienation from the natural unconscious state of wholeness…in order to emerge at all, the ego is obliged to set itself against the unconscious out of which it came and assert its relative autonomy by an inflated act…Any step in individuation is experienced as a crime against the collective.

Campbell notes that rites of passage

…are distinguished by formal, and usually very severe, exercises of severance, whereby the mind is radically cut away from the attitudes, attachments, and life patterns of the stage being left behind.

Orestes had spent most of his youth at the court of his uncle Strophius, king of Phocis. He had been educated along with Pylades, and they had become close friends. Though Strophius does not appear in the play, and Pylades has but one, though crucial, line, the legend may be implying that Orestes’ initiatory process had already begun among the older men at Phocis.

Bly, once again, cautions us not to blame the mother but the absent father:

We must repeat that it isn’t the personal mother who imprisons the son…lt is the possessive or primitive side of the Great Mother that keeps him locked up…One needs to be able to say these truths without laying a lot of blame on the mother, for Freud has already singled her out, wrongly, for the main responsibility. The whole initiatory tradition, of which Freud knew very little, lays the primary responsibility on men, particularly on the older men and the ritual elders. They are to call the boys away. When they don’t do that, the possessive side of the Great Mother will start its imprisonment…

Orestes’ momentous act of cutting the chord between him and his mother was but one step in a lifelong process of grief and reconciliation. However, his path to initiation is not the only one we find in Greek myth. In two other essays, The Spell of the Mother and Male Initiation and the Mother in Greek Myth, I compare him to his cousin Telemachus and other figures, including Dionysus, Herakles, Oedipus, Hephaestus and Pentheus.

Part Eight

Sing sorrow, sorrow, but good wins out in the end – Aeschylus

If we do not transform our pain, we will most assuredly transmit it. – Richard Rohr

Whoever isn’t busy being born is busy dying. – Bob Dylan

The Eumenides

In the final play of the trilogy Orestes, pursued by the Furies, traveled from Apollo’s sanctuary at Delphi to Athens. The gods had referred his fate to Athena and a jury of mortal men. When their vote came out even, the Goddess cast the tie-breaking vote in favor of Orestes, and the Furies were propitiated by a new religious cult.

How do we resolve the conflict between fate and justice? The Furies (or Erinyes in their primitive form) argued that fear consequent on wrongdoing is the basis of law, humility and respect, that without loyalty to kin there is chaos; while Apollo, defending Orestes, appealed to duty.  The play also presents a secondary theme, the older, matriarchal order vs. the newer, patriarchal one. The Furies, bloodthirsty in their desire for revenge, insisted on the fact against the idea, ignoring Orestes’ motivations. Apollo responded with arrogance and threats. Richard Lattimore describes the resolution:

The play also presents a secondary theme, the older, matriarchal order vs. the newer, patriarchal one. The Furies, bloodthirsty in their desire for revenge, insisted on the fact against the idea, ignoring Orestes’ motivations. Apollo responded with arrogance and threats. Richard Lattimore describes the resolution:

Athene, whose nature reconciles female with male, has a wisdom deeper than the intelligence of Apollo. She clears Orestes but concedes to the detested Furies what they had not known they wanted, a place in the affections of a civilized community of men, as well as in the divine hierarchy. There, gracious and transformed though they are, their place in the world is still made potent by the unchanged base of their character…Man cannot obliterate, and should not repress, the unintelligible emotions. Or again, in different terms, man’s nature being what it is and Fury being a part of it, Justice must go armed with Terror before it can work…Thus, through the dilemma of Orestes and its resolution, the drama of the House of Atreus was transformed into a grand parable of progress. Persuasion…has been turned to good by Athene as she wins the Furies to accept of their own free will a new and better place in the world.

But we continue to ask, in which direction does the energy move? Who are these women? “Fury” comes from the Latin “to rage”. They may represent a part of ourselves that rages against other parts of ourselves. The Erinyes, according to Hesiod, were the daughters of Earth and sprang from the blood of the mutilated Ouranos. Aeschylus calls them daughters of Night. In Sophocles, they are daughters of Darkness and Earth. Their names are Alecto (unceasing in anger), Tisiphone (avenger of murder) and Megaera (Jealous). They rise from their home below to punish the worst transgressions.

The underworld is the unconscious. The Erinyes emerge from the deep self, forcing themselves upon ego consciousness with vitally important messages, although the whole history of humans and gods as told in these eight generations describe our infinitely varied attempts to ignore them. The messages are simple: Something is terribly wrong here! You have unfinished business to deal with.

We may experience them variously as guilt or shame, depending on whether we feel, deep inside, that we have done something wrong, or that we are something wrong. All our ego defenses are attempts to avoid these feelings and the pain that arises with them. However, as we have noted, since they present us with the reality of our original childhood wounds, they also offer opportunities for healing.

As above, so below. Orestes’ struggle mirrored the earlier experience of his initiator Apollo, who had also confronted the female principle. He had come to Delphi as a child, where he killed Python, its original guardian, and expiated his crime by serving the mortal Admetus for eight years. Apollo knew a thing or two about restitution, or restorative justice.

But Orestes experienced the symbolic death of his old self and the descent into madness.

Perhaps his grief was not merely for himself but for both his criminal ancestors and his descendants. (We recall the Native American Haudenosaunee /Iroquois tradition that the decisions we make should result in a sustainable world seven generations into the future.) Yet only after years of atonement would Athena and the elders of Athens judge him as sufficiently transformed to be admitted to the community of mature adults, the polis.

How has time moved? At the beginning of the play, Apollo’s priestess described the tormented Orestes, surrounded by the sleeping Furies “with blood dripping from his hands and from a new-drawn sword.” But the implication is that much time has passed. In myth, one day can equal many of our years, wrote Edith Hamilton:

When next he came to his country, years had passed. He had been a wanderer in many lands, always pursued by the same terrible shapes. He was worn with suffering, but in his loss of everything men prize there was a gain too. “I have been taught by misery,” he said. He had learned that no crime was beyond atonement, that even he, defiled by a mother’s murder, could be made clean again…the black stain of his guilt had grown fainter and fainter through his years of lonely wandering and pain.

The Erinyes arose from their sleep for one final dispute. Or perhaps if healing occurs in a spiral pattern, they arise periodically as the initiate approaches each new stage. Having directed Orestes to flee to “Pallas’ Citadel” (Athens), Apollo prophesied that suffering will turn intelligence into wisdom:

Thus you will be rid of your afflictions, once for all. For it was I who made you strike your mother down.

Apollo claimed that “the wanderer has rights which Zeus acknowledges.” The movement is from the head-intelligence he symbolizes to the heart-wisdom of Athena.

Orestes was, in a sense, playing with fire, evoking his devils along with his angels. The Erinyes could shift back and forth from guilt-messengers to shame-messengers:

Cursed suppliant, he shall feel against his head another murderer rising out of the same seed.

In the final scene, Orestes came as a suppliant to the statue of Athena on the Acropolis,

…blunted at last, and worn and battered on the outland habitations and the beaten ways of men.

The Furies threatened to drag him down to Hades, but Orestes responded that he had already experienced the most profound suffering:

I have been beaten and been taught. I understand the many rules of absolution, where it is right to speak and where be silent. In this action now speech has been ordered by my teacher, who is wise. The stain of blood dulls now and fades upon my hand. My blot of matricide is being washed away. When it was fresh still, at the hearth of the god, Phoebus (Apollo), this was absolved and driven out by sacrifice of swine, and the list were long if I went back to tell of all I met who were not hurt by being with me. Time in his aging overtakes all things alike.

Orestes had accomplished the initiatory transition from “Hero” to “Warrior”. Robert Moore described these two archetypes:

There is much confusion about the archetype of the Hero…The Hero is, in fact, only an advanced farm of Boy psychology – the most advanced form, the peak, actually, of the masculine energies of the boy, the archetype that characterizes the best in the adolescent stage of development. Yet it is immature, and when it is carried over into adulthood as the governing archetype, it blocks men from full maturity…the Hero is overly tied to the mother (and) has a driving need to overcome her.

By contrast, the Warrior is an aspect of mature, initiated masculinity, capable of protective, restrained, aggressive action in the service of a transpersonal goal:

When the Warrior is connected with the King, he is consciously stewarding the “realm,” and his decisive actions, clarity of thinking, discipline and courage are, in fact, creative and generative.

“The list were long” of those whom Orestes had met and not harmed. Though fully capable of aggressively passing on the energy, he had remained focused on his goal of transformation through grief. By the beginning of the play, Orestes had already achieved his healing. The trial that followed merely confirmed this truth:

lt is the law that the man of the bloody hand must speak no word until, by action of one who can cleanse, blood from a young victim has washed his blood away. Long since, at the homes of others, I have been absolved thus, both by running waters and by victims slain.

The waters were his own tears, and the victims were parts of himself, for, as Bly writes, “Some deaths stand for the naiveté that dies when the son accepts the father’s world.”

The Erinyes grudgingly mirrored lines spoken in Agamemnon:

There is advantage in the wisdom won from pain.

At this point I acknowledge that feminist scholars, for good reasons, have long considered the Oresteia a foundational text of patriarchy and can offer many statements by both Apollo and Athena as proof. But we also need to understand that myth can provide many levels of meaning. I encourage readers to stay focused on the symbolic meaning.

On one level, the verdict of innocence (even if it took Athena’s tie-breaking vote) was certainly a condemnation of the feminine; but on another it was further confirmation of Orestes’ transformation. The sacrifice of his innocence had resulted in the achievement of his father’s blessing, symbolized by his assumption of the throne of Argos:

Among the Hellenes (Greeks) they shall say: “A man of Argos lives again in the estates of his father…”

Finally, Athena persuaded the Erinyes to accept their own initiation into a new role in society and religion.

The focus of events had shifted from Argos, city of conflict, to Athens, city of wisdom. In yet another process of enantiodromia, the Erinyes were transformed into something very much like their opposites. They became the Eumenides, the “kindly, well-disposed ones”. At the end of the play, their rite de passage from Erinyes to Eumenides was symbolized by a grand procession through Athens. Subjectively, this is confirmation that grief fully experienced can lead ultimately to healing. Edith Hamilton concludes:

“…I have been cleansed of my guilt.” These were words never spoken before by any of the House of Atreus. The killers of that race had never suffered from their guilt and sought to be made clean…with the words of acquittal the spirit of evil which had haunted his house for so long was banished. Orestes went forth from Athena’s tribunal a free man. Neither he nor any descendant of his would ever again be driven into evil by the irresistible power of the past. The curse of the House of Atreus was ended.

Part Nine

To be born is to be weighed down with strange gifts of the soul, with enigmas and an inextinguishable sense of exile. – Ben Okri

… wounds to the soul take a long, long time, only time can help

and patience, and a certain difficult repentance, long difficult repentance, realization of life’s mistake, and the freeing oneself from the endless repetition of the mistake, which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify. – D. H. Lawrence

Alternative Stories

Like all the great myths, this story generated countless variants. The Athenians claimed that their ancestors had shunned the tormented Orestes, forcing him to do his drinking alone. Much later, they incorporated this memory into the celebration of their Anthesteria festival, as if to imply that even after the verdict of innocence, the Furies still followed him.

This aspect of public ritual seems to fit the massive paradox of a civilization – not unlike our own – that praised individual freedom, equality and philosophical enquiry but was in fact a brutal empire that couldn’t function without slave labor.

In another story, Orestes killed Aletes, son of Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, took the throne of Mycenae and married their daughter Erigone, who bore a son named Penthilus. Some say the child was killed by wolves, and that his father established a festival of mourning, the Penthilia, in his honor. Others say he (the ninth generation) survived, founded a city and became the ancestor to another dynasty of kings. Others assert that Erigone brought Orestes to another trial for the murder of her mother and hanged herself when he was acquitted.

Still others said that Menelaus and Helen’s daughter Hermione (“Harmony”) had been betrothed to Achilles’ son Neoptolemus. Orestes killed him and married Hermione, who bore him a son, Tisamenus (another member of the ninth generation). Orestes then gave Electra as wife to Pylades, and both couples lived in peace. In this version, Orestes lived to a very old age and died, curiously, of a snakebite (on his heel, like Achilles). Bly notes another tale:

…Orestes, while being pursued by the Furious Invisible Women, after he murdered his mother, bit off a finger and threw it at them; when they saw that, some of them turned white, and left him alone.

Perhaps the finger symbolizes not phallic potency but the brittle masculine armoring that veils the insecurities of those who haven’t cut the maternal chord. Finally, writes Calasso,

…years later, people came to look for his bones, for much the same reason that had prompted other people to look for the bones of his grandfather Pelops.

Grief , Suffering and Redemption

We recall Jung’s statement that all neurosis is but a substitute for legitimate suffering. Cutting past neurotic suffering (our vast arrays of compulsions, addictions, and dysfunctional styles) to legitimate, or authentic suffering, we open to the possibility of attaining knowledge, and we are back to Aeschylus: “Justice so moves that those only learn who suffer.” And what moves us from neurotic suffering to legitimate suffering to knowledge is the active decision to open up to grief.

Just as there are two forms of suffering, there are two forms of grief. In the first, we grieve what has happened to us, what we have lost, never had or know we will lose in the future. Francis Weller, in The Wild Edge of Sorrow, writes that any of us can enter the great communal hall of grief through any of five gates:

1 – Everything We Love, We Will Lose

2 – The Places That Have Not Known Love

3 – The Sorrows of the World

4 – What We Expected and Did Not Receive

5 – Ancestral Grief

If we can learn to walk the fine line between numbness and acting out, if we can withstand the temptation to pass the energy onward to others, our grief can lead to healing. The emotion associated with this form of grief is shame. Initiation into adulthood offers the possibility of transmuting this shame into self-esteem.

With the one exception of Niobe, none of Orestes’ ancestors grieved their personal losses or pain. No one cried out that their parents “ate” their individuality, abused them, neglected them, or used them as surrogate spouses. Since children believe that their pain was their own fault, perhaps this is the original cause of neurotic suffering.

The second major form of grief rises from guilt for the harm we have done. We grieve the consequences of our (or our group’s, community’s, nation’s, race’s, etc.) actions upon others (exterior or interior). We accept that we did something wrong, not that we are something wrong. We have acted wrongly, we admit the guilt, and we grieve. Theologically, we have sinned, and hope for redemption through repentance. So, to simplify, we grieve that others have sinned against us, or we grieve because we have sinned against others. And no one in the Oresteia or any of its preceding generations has accepted the terrible burden of either of these griefs until we meet Orestes and Electra.

These two forms of grief meet in the murder of Clytemnestra. The mother-complex will keep a man from experiencing his original wounds, what happened to him. Ideally, cutting through to that core (work facilitated by the male initiators) releases the bound up energy that leads to both painful knowledge and healing.

But separation from the mother risks separation from the feminine in its positive aspects as well. It really is a choice of the lesser of two evils. The major part of Orestes’ grief is the second kind, an acknowledgement of guilt, a cry of remorse for what he had to do.

Bly taught that there is a component of grief in the male psyche which is not present to the same degree in the female. Perhaps this is what he meant: men, to grow up, must give up their deepest emotional attachment, the most important thing they have. And for this reason, they must endure a guilt, and a grief, that women, for all their sorrows, don’t know, because they generally do identify with their mothers. In time, men may re-establish a relationship to that inner feminine, but that is a different initiation and calls for different stories. Perhaps the fact that Athena is the arbiter of Orestes’ fate indicates that his healing path will ultimately achieve a balance between the feminine and the masculine.

We also note that the Athenians had a word for those who refused to participate in public life: idiota. Perhaps Aeschylus was also describing the condition of those who act in the realm of politics, who must continually compromise between evils, where the perfect too often is the enemy of the good.

I’ve quoted Bly often to emphasize that participants in the men’s conferences that he began have confronted these issues for two generations. He always insisted on the active nature of grief. After spending lifetimes searching for pleasure and avoiding pain, at some point we must decide to go down into grief. Bly distinguished grief from depression using an image from the old story Iron John: if we refuse the imperative to descend, a hand may come up from the water, grab us, and pull us down, perhaps for good. That, said Bly, is depression. If we choose to go down, however, we retain the option of someday choosing to come back up. In this spirit, Orestes chose one kind of death so that his real life could begin.

Bly emphasized that the development of male consciousness is a spiral movement, as men go through the various stages of initiation incompletely, sometimes embodying several stages at once. In this continual returning, the mother complex is not murdered in a single stroke of a sword:

For Hamlet it meant giving up the immortality or the safe life promised to the faithful mother’s son, and accepting the risk of death always imminent in the father’s realm…When a man has reclaimed his grief and investigated his wound, he may find that they resemble the grief and the wound his father had, and the reclaiming puts him in touch with his father’s soul…Moving to the father’s world does not necessarily mean rejecting the mother or shouting at her – Hamlet is off in that respect – but rather the movement involves convincing the naive boy…to die. Other interior boys remain alive; this one dies…But independence from the mother’s womb world goes in agonizingly slow motion for developing men. One wants to run, but the legs will not move. We wake exhausted.

However, concludes Alice Miller,

That probably greatest of narcissistic wounds – not to have been loved just as one truly was – cannot heal without the work of mourning…When the patient, in the course of his analysis, has consciously repeatedly experienced (and not only learned from the analyst’s interpretations) how the whole process of his bringing-up did manipulate him in his childhood, and what desires for revenge this has left him with, then he will see through manipulation quicker than before and will himself have less need to manipulate others. Such a person will be able to join groups without again becoming helplessly dependent or bound…in less danger of idealizing people or systems…a person who has consciously worked through the whole tragedy of his own fate will recognize another’s suffering more clearly and quickly…He will not be scornful of another’s feelings, whatever their nature, because he can take his own feelings seriously. He surely will not help to keep the vicious circle of contempt turning.

This is our dual condition, as told in the myths: It’s always been this way – and healing is possible. The bad news is that the old initiation rituals are nearly gone. More than ever, the most powerful people are deeply wounded, desperate to deny their pain by passing it on to others, and willing to destroy all life in the process.

The good news is that we have never lost the ability to imagine, and that we have greater access to old wisdom than our parents had. Anthropologist Angeles Arrien used to teach a guided meditation from her Basque tradition:

Imagine seven generations of your male ancestors emerging from the underworld to stand behind your right shoulder. Imagine seven generations of your female ancestors behind your left shoulder. Imagine that as you enter the fire of initiation, they are speaking with great excitement to each other:

"Oh, may this be the one who will bring forward the good, true and beautiful in our family lineage. Will this be the one to break the harmful family or cultural patterns? Oh may this be the one to break the curse! May it be so!"