Part 1 – Framing the Message

Most American men above the age of sixty who learned about masculinity by watching John Wayne movies as children are familiar with this melody without knowing its name, let alone its history. Here it is.

Recognize it? The tune is called “Garryowen,” and it has been featured as a military marching song in several movies, including The Fighting 69th, They Died with their Boots On, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, The Long Gray Line, Little Big Man, Son of the Morning Star, Gangs of New York, Rough Riders and We Were Soldiers Once… And Young.

But it is far older than Hollywood, and it has a fascinating history. The tune is first documented as an Irish jig, Auld Bessy, in 1788. The word Garryowen combines the proper name Eóghan (“born of the yew tree”) and the word for garden garrai – thus “Eóghan’s Garden.” It refers to the neighborhood of Garryowen (first described in the 13th century) near the city of Limerick, a general rendezvous for those with leisure time on their hands and hell to raise. These young gentlemen amused themselves by vandalizing street lamps, harassing passers-by, beating up workingmen and singing Garryowen:

Let Bacchus’ sons be not dismayed,

But join with me, each jovial blade;

Come booze and sing, and lend your aid,

To help me with the chorus.

CHORUS:

Instead of spa we’ll drink down ale,

And pay the reck’ning on the nail;

No man for debt shall go to jail

From Garryowen in glory,

We are the boys that take delight in

Smashing the Limerick lights when lighting,

Through the streets like sporters fighting

And tearing all before us. (Chorus)

We’ll break windows, we’ll break doors,

The watch knock down by threes and fours;

Then let the doctors work their cures,

And tinker up our bruises. (Chorus)

We’ll beat the bailiffs out of fun,

We’ll make the mayor and sheriffs run;

We are the boys no man dares dun,

If he regards a whole skin. (Chorus)

Our hearts so stout have got us fame,

For soon ’tis known from whence we came;

Where’er we go they dread the name

Of Garryowen in glory. (Chorus)

This drinking song – it calls upon Dionysus, or Bacchus – soon became very popular among British soldiers who, along with these Protestant Irish, were engaged in the centuries-long, settler-colonialist suppression of Catholic Ireland.

A quick look at the lyrics might elicit a “boys will be boys” response. Yes, these “boys” brag of their rowdy but good-natured adolescent behavior (known in other contexts as “gang” behavior), but the deeper meaning is that this is the folk music of privilege. These were sons of the Protestant rulers who knew that they could expect few consequences for their destructive actions. At the same time, in America, the sons of Southern planters enjoyed similar privileges, including the right to rape their slaves. For a contemporary comparison, consider the West Bank area of Palestine, where Jewish settlers abuse their Palestinian neighbors, knowing that they are protected by the Israeli military. This is settler colonialism.

Back in Ireland, the Catholics lost their land and most of them became dirt-poor. Because of their impoverished condition, many generations of their young men had little choice but to join the army and become mercenaries for the very empire that had conquered them. They sang Garryowen in the Napoleonic Wars and the Crimean War. Later, the tune became associated with a number of British military units, as well as theIrish Regiment of Canada.

But this is an American story. It’s about how we frame the stories that we tell ourselves about ourselves.

The Protestant Scots-Irish were one of the largest ethnic groups to settle the American South during the 17th and 18th centuries, some as freemen and thousands of others as indentured servants. Some prospered in the atmosphere of white privilege that they encountered, and they participated in the western migration over the mountains. In the 19th century they formed the backbone of the Confederate army. At least half of all American Presidents have Scots-Irish blood.

The Catholic Irish began to come to America in the 1840’s, as refugees from the Great Famine. The failed revolution of 1848 forced many more of them to emigrate, mostly to the large northern cities, where many joined the U.S. army. Some of them deserted during the Mexican war, formed the “St. Patrick’s Battalion”, fought on the Mexican side and inspired their own songs.

In 1851 they formed the first Irish-American regiment, New York’s 69th, the “Fighting Irish,” made famous by the James Cagney film, The Fighting 69th. And they brought Garryowen with them as their marching tune.

As they continued to arrive in the 1860’s, thousands found themselves impressed into the Union army almost as soon as they disembarked in New York. Once again, as in Ireland (and as in the next century), the Irish found themselves on opposite sides in a Civil War, which was in large part fought between Irish Protestants of the South and Irish Catholics of the North. The 69th saw considerable action, and many others heard them singing Garryowen.

Another tune popular on both sides was When Johnny Comes Marching Home. Soldiers and civilians sang it as they looked forward to the return of the victorious – and healthy – soldiers:

When Johnny comes marching home again

Hurrah! Hurrah!

We’ll give him a hearty welcome then

Hurrah! Hurrah!

Oh, the men will cheer and the boys will shout

The ladies they will all turn out

And we’ll all feel gay when

Johnny comes marching home

This song eventually entered the canon of universally acceptable and teachable American pop-folk music. I remember singing it in grammar school in the 1950s ninety years after the end of the war. Its melody is so catchy (in its speeded-up form) that it may be more popular now as a silly children’s tune.

Some say that the song, however, was a rewrite of the much older and much darker Irish lament Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye, which describes the true cost of war on one returning and very damaged soldier and his wife (others disagree, arguing that both songs were created in the 1860s). For another example of the evolution of a song associated with the Civil War, see my essay Driving Dixie Down.

There are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry. – George Armstrong Custer

After the war, many Irish veterans of the 69th joined George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry, bringing their song along with them. In the winter of 1868, a mere three years after they had “fought to make men free”, they became complicit in destroying the freedom of Native Americans so that Euro-Americans could expand across the continent.

On the Washita River in western Oklahoma, the regimental band played Garryowen to signal the attack on a peaceful Cheyenne village that resulted in a massacre of over 100 Indians. Eight years later, it was the last tune played as they rode out towards the Little Big Horn.

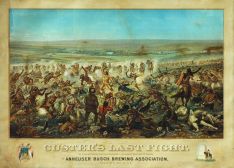

By that time the narrative of Western expansion, in which benevolent and god-fearing men led a new nation that was morally and physically destined to fill a continent and spread freedom everywhere (deterred only by bloodthirsty savages), was already two hundred years old. But the story of “Custer’s Last Stand”, depicted over the years in some 300 books and 1000 paintings (one of which was reproduced over a million times),

established its mythic status. And 45 movies and TV shows.

Hollywood connected Garryowen with John Wayne and made it recognizable to millions by including versions of it in every movie it made about Custer. Here, in They Died With Their Boots On, with Errol Flynn in the lead role, is Warner Brothers’ version of how it was adopted as the quintessential Cavalry soundtrack. Watch the whole three-minute clip to get a full sense of its mythmaking power.

Hollywood connected Garryowen with John Wayne and made it recognizable to millions by including versions of it in every movie it made about Custer. Here, in They Died With Their Boots On, with Errol Flynn in the lead role, is Warner Brothers’ version of how it was adopted as the quintessential Cavalry soundtrack. Watch the whole three-minute clip to get a full sense of its mythmaking power.

Fourteen years after Custer’s defeat the 7th Cavalry achieved its revenge when it massacred over 300 Lakotas at Wounded Knee in 1890. It went on to serve in all the wars of the 20th century, and to this  day it sports this regimental crest.

day it sports this regimental crest.

In 1905, the regiment added their own official lyrics:

We are the pride of the Army

And a regiment of great renown.

Our name’s on the pages of history

From sixty-six on down.

If you think we stop or falter

While into the fray we’re going

Just watch our steps with our heads erect

While our band plays Garryowen.

In the Fighting Seventh’s the place for me,

It’s the cream of all the cavalry;

No other regiment can ever claim

Its pride, honor, glory and undying fame…etc

Popular myth uses the evolution of these men from ethnic outcasts to defenders of the westward expansion to liberators of oppressed people everywhere as a metaphor for the nation itself. The 2006 film Rough Riders uses the (by now) stirringly patriotic Garryowen to show how the nation “healed” the wounds of the Civil War (by rejecting Reconstruction’s attempt to mandate racial equality) and became unified. As the band plays and the soldiers embark to “liberate” Cuba from Spain, a surprised young Southern boy remarks to his grandfather, a former Confederate, “They’re Yankees.” The old vet proudly responds, “No, they’re Americans!”

The Seventh Cavalry traded in its horses for tanks in World War Two and for helicopters when the U.S. invaded Viet Nam. It became the “Air Cavalry” that was depicted re-enacting its Washita massacre by attacking a “hostile” village in Apocalypse Now. And despite that film’s fictional usage of Ride of the Valkyries, the regiment has retained Garryowen as its official tune. (Actually, that scene may not be totally fictional: the 7th had also perpetrated the massacre at No Gun Ri in Korea in 1950, killing between 200 and 400 civilians).

Regardless, by the end of the 20th century Garryowen had become synonymous with patriotic service in the armed forces, and the name was being used in many contexts. There is a Camp Garry Owen in South Korea, and there was a base Garryowen during the invasion of Iraq. Indeed, the fact that the “Air Cav” has used Garryowen as the soundtrack for a recruitment video is evidence of how familiar it is to young men in this country. The phrase is used as a password in combat conditions. Members of the regiment shout “Garryowen!” to each other, in the same way that Marines shout “Hoo-rah!” It is now the soundtrack for a nation of uninitiated, macho men who have dedicated themselves to killing the Others of the world, to maintain a mythology of exceptionalism and innocence. There is a Garryowen Pub in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

The culture of death has an appetite for images, even those images that true artists create. Ronald Reagan co-opted Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA; beer and car companies sponsor tours by musicians; loudspeakers play We will rock you as the bombers take off; CIA torturers blast Heavy Metal into prisons to disorient prisoners; and Jimmie Hendrix’s Voodoo Child is played at boot-camp initiations. Skinheads sell racist rock over the Internet, while misogyny drives much Hip Hop. The volume increases as civic involvement declines.

Our myths, including the myth of American Innocence, are conveyed through images. It is easy enough to understand the effect of graphic images – pictures, film, TV and digital – but sound images also contribute to the regular socialization of the young and the internalization of group norms. Some researchers call this process entrainment, and music is integral to its effect. To feel the impact of Garryowen, simply re-play any of the music video links in this essay and imagine yourself marching to it, along with hundreds of young men desperate for initiation, desperate to serve a cause, any cause. Or, in its 19th century context, image yourself astride a stallion, prancing along to the regimental band with Errol Flynn.

Or: imagine the tune slowed way down in tempo.

Part Two – Reframing the Message

Myths change very slowly, but they can transform when enough of us begin to consider (“to be with the stars”) our unconscious attention to the stories we have been telling ourselves about ourselves. This is likely to be a painful process; perhaps that’s why it is called paying attention. And it may require that we counter the voracious god of Time – Kronos – by slowing down our unconscious responses to the parade of both mental (internal) and environmental (external) imagery that constantly bombards us, or in this context, the military parade.

Learning

A piccolo played, then a drum.

Feet began to come – a part of the music.Here comes a horse, clippety clop, away.

My mother said, “Don’t run –

the army is after someone other than us.If you stay you’ll learn our enemy.”

Then he came, the speaker.

He stood in the square. He told us who to hate.

I watched my mother’s face, its quiet.

“That’s him,” she said. – William Stafford

The musical examples I’ve used in this essay are instructive. Consider the emotional difference between the up-tempo When Johnny Comes Marching Home and the slow lament Johnny I Hardly Knew Ye.

Part of the necessary practice of reframing our myths requires deliberately, and perhaps painfully, sorting out the images and imagining how to perceive them as if they were meant to deepen our soul work instead of reinforcing our nationalist prejudices. One songwriter, Robert Emmet Dunlap, has done just that with the Garryowen tune – by slowing it down and adding new lyrics that put Custer and the Seventh Cavalry into a very different perspective. As Native American writer Vine DeLoria wrote, Custer Died For Your Sins. Reframing Garryowen and the entire mythic framework that it evokes means excavating the emotions of pride, aggression and group identity to find the deep grief that underlies them.

Dunlap explains:

“Mick Ryan’s Lament” is a ghost story about two brothers who escape post-famine Ireland for the Land of the Free, and fight for the Union in the War Between the States. Mick stays in the army and ends up dying with Custer at Little Big Horn; forever haunted by, and to, the tune of “The Garryowen.” (official tune of the 7th Cavalry and the fighting 69th, and God knows how many military units full of Irishmen fighting for flags that were not green, and lands that were not Ireland).

Here are two renditions of Mick Ryan’s Lament:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=–qvlaWL9R8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Emy4pGBetyk

Here are the lyrics:

Well my name is Mick Ryan, I’m lyin still

In a lonely spot near where I was killed

By a red man defending his native land

In the place that they call Little Big Horn

And I swear I did not see the irony

When I rode with the Seventh Cavalry

I thought that we fought for the land of the free

When we rode from Fort Lincoln that morning

And the band they played the Garryowen

Brass was shining, flags a flowin

I swear if I had only known

I’d have wished that I’d died back at Vicksburg

For my brother and me, we had barely escaped

From the hell that was Ireland in forty eight

Two angry young lads who had learned how to hate

But we loved the idea of Amerikay

And we cursed our cousins who fought and bled

In their bloody coats of bloody red

The sun never sets on the bloody dead

Of those who have chosen an empire

But we’d find a better life somehow

In the land where no man has to bow

It seemed right then and it seems right now

That Paddy he died for the union

Ah, but Michael he somehow got turned around

He had stolen the dream that he thought he’d found

Now I never will see that holy ground

For I turned into something I hated

And I’m haunted by the Garryowen

Drums a beating, bugles blowin’

I swear if I had only known

I’d lie with my brother in Vicksburg

And the band they played that Garryowen

Brass was shin, flags a flowin’

I swear if I had only known,

I’d lie with my brother at Vicksburg

The song is so resonant because in changing the cavalry cadence to a dirge of disillusionment and regret it reverses the upward arc of the hero – and the heroic nation. The American Hero expresses radical individualism, potency, production, infinite growth and racist, manifest destiny. But perhaps he conquers the Others of the world because in saving the world he thinks he can save himself.

Garryowen, after all, is a theme for men who boast, drink, brawl and fight in places where they were never invited. They are the kind of men who can (and did) refer to Viet Nam as “Indian country” and its civilians as “gooks.” And in this context, they were the kind of men who proudly flew the Confederate battle flag in World War Two,  Viet Nam and Iraq.

Viet Nam and Iraq.

From an indigenous perspective, however, they – and the politicians who send them – are uninitiated men, who attempt to find meaning through the most literal of initiations.

But all indigenous mythologies understand that the Hero must die. That is, he must eventually enter the flames of initiation, shed an outmoded sense of himself and return to be in service to the greater collective. This individualizing process requires that he pass through the realms of reconsideration, regret and remorse. He must die symbolically so that he can be reborn.

Mick Ryan’s Lament does this by turning an anthem of uninitiated men into a cry of regret for having “turned into something I hated” sung by a ghost. It expresses the pain of any veteran of any colonial war who realizes what he has turned into – or of any soul that has come to consciousness and had its innocence or false identity shattered. It carries those emotions, but it also carries potential, the terrible knowledge that only from such deep loss can any new birth arise. The protagonist’s body lies at the Little Big Horn, but his soul resides among the ancestors. The Hero has died to become one of them. The tragedy is that he had to die literally to do so.

Disillusionment and the death of the Hero can lead to cynicism, self-hatred and, for so many veterans, suicide. But mythology leaves open the possibility of transformation into something greater than the Hero – the archetype of the Warrior. Psychologists such as Ed Tick and Jonathan Shay have brought such mythological thinking to their work with war veterans, PTSD and the moral injuries they suffer from. For more on this issue see my essay Myth, Memory and the National Mall.

People can change. If enough people change, a culture can change. Reconciliation is possible. We recall Custer’s massacre of the Cheyenne on the Washita River in 1868. On its 100th anniversary in 1968 (while the 7th Air Cavalry was on active duty in Viet Nam), descendants of the Indian survivors met in a ceremony with descendants of the perpetrators, whose leader told the Cheyenne elders: “We are sorry that ‘Garryowen’ was played that day 100 years ago and never again will it be played against your people.’”

And some versions of Johnny We Hardly Knew Ye have an added, final verse:

They’re rolling out the guns again, hurroo, hurroo

They’re rolling out the guns again, hurroo, hurroo

They’re rolling out the guns again

But they won’t take back our sons again!

No they’ll will never take back our sons again

Johnny, I’m swearing to ye.

This is how we can imagine reframing the myth of American innocence – one image, one song at a time.