Part One

What went before, as told by those who think they know it. – Gary Snyder

Everything comes to the reader as interpreted by the historian. Everything is seen through the medium of his personality. The facts of history when they are used to teach a moral lesson do not reach us in their entirety…but selected and arranged according to the overmastering ideal in the mind of the historian. The reader is at the historian’s mercy. – Peter Novick

History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it. – Winston Churchill

I invoke the muse of history, Clio, daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne (Memory).

Book banning in America dates back to 1637, a year after Harvard College was founded. Recent efforts across the country have hit their highest level in twenty years, partially because in 2021 Fox News stoked the Culture Wars by mentioning critical race theory 1,300 times in four months. Now, Senate candidates are going full-paranoid on white replacement theory.

Along with the threats, the levels of comic hypocrisy have gone through the roof. Republicans can’t resist mis-quoting Martin Luther King Jr. One of the groups lobbying for book banning is Moms For Liberty! Meanwhile, a “scholar” from the American Enterprise Institute suggests, “Ban critical race theory now. States must assert the power to enforce the principles of the Civil Rights Act!”

At least four states have done that, and another dozen are debating the issue, which is – do I really need to say this? – performative idiocy at best, and cynical, unrepentant racism and misogyny at worst. In addition, dozens of states are or soon will be considering anti-LGBTQ bills. And now we have the mendacious Supreme Court admitting its plans to ban abortion rights by citing a 17th-century witch hunter. Gotta laugh to keep from crying.

Everywhere, reactionaries are scurrying to shore up the latest cracks in the façade of the myth of American innocence by controlling the narrative of history, how it is taught and even if it is taught.

It’s all being done, of course, by Republicans, usually in safely Republican states, meant primarily as entertainment for the choir, since most public and private history education in those states has already been controlled for generations by the racists and religious inquisitors who have served as the gatekeepers of culture and memory in the former Confederacy. I’ve addressed this theme in detail here. Naturally, powerful Southerners want to retain their influence by any means, including perpetuation of ignorance, division of the working class and outright violence.

They want to decide how their – and increasingly your – children think and what they know about two main issues characteristic of 1950s white thinking. The first would accept discrimination based on race, gender and sexual orientation as reflections of acceptable traditional values.

The second – propelled mostly by Democrats – involves reviving the old Cold War narrative of a bipolar world. One side, led by the United States, is allegedly a “free world”, a “global community” whose intentions are universally benign, and the other, led by Russia and China, is a hostile, dictatorial and expansionist world. Pure black and white.

But this essay is pursuing bigger game. For most of human history, the shamans and poets and later the priesthood served as the gatekeepers of culture, channeling their populations into the narrow confines of acceptable opinion regarding everything from personal behavior to national identity to which “Other” people to hate. The result is what used to be our generally agreed-upon collective memories, which Jeremy Yamashiro describes as

…those representations of the shared past that members of a community hold in common. Collective memory is different from history. Whereas historians aim to create a relatively objective account of the past using rigorous professional standards of what counts as evidence, when members of a community recall their collective past, they do so through the filter of a contemporary set of concerns…These selective renderings help us create imagined communities – nations, races, religions, “the West” – by endowing those communities with a story of continuity and self-sameness across time.

Do historians create objective accounts of the past? Is there work really any different from collective memory? We’ll have to see about that.

Another way of talking about collective memory is to use the language of mythology. Joseph Campbell taught that a living myth refers past itself to the ineffable, serving four distinct functions. The mystical function introduces the individual to that which underlies all names and forms. It awakens religious awe, humility and respect. Second, the cosmological function explains how the universe works. Third, the pedagogical function defines a moral life as defined by each culture.

Fourth – and most pervasive – the social function validates the social order and integrates individuals within it. Originally, this was a good thing: it oriented people to the mystery by presenting noble figures at the center of the realm who radiated the blessings that flowed through them from the other world. These figures showed that everyone carried such potential.

The word “noble” is related to “knowledge.” A noble, mythologically speaking, is one who knows him or herself. If people still revere royalty in places like Britain and Thailand, they may be accessing some vestigial memory of what the sacred King once meant. We know who we are and where we fit in because the gatekeepers have taught us. However, in modern culture, “it is this sociological function of myth that has taken over,” wrote Campbell, “…and it is out of date.”

When I speak of myth in this article, I am referring to it as it has devolved in a world that, as Campbell wrote, is demythologized. That is to say, the first three functions are essentially gone, and we are left with only the fourth, sociological function. In a demythologized world this function is essentially identical with the narratives put forth by the ruling elites to serve only their interests. It does not feed the soul, and when we are honest with ourselves, we admit it.

But we need stories to tell us who we are, even if we know they are false. They provide us with a bare minimum of truth about ourselves, just enough to keep us alive (in Chapter Ten of my book I write about Robert Johnson’s concept of “low-quality Dionysus”). And it’s possible that even such low-quality mythologies may lead us to deeper mysteries.

Myth shapes our values, organizes our experience, brings emotion to our festivals and sacrifices, sets the boundaries of dissent, names the children, sends them off to war and justifies their deaths. It is the most compelling story we tell ourselves about who we are, especially when we hear it from the noble ones, those upon whom we project our own nobility. And frequently it is the story of who we are not – the Other. Howard Zinn wrote:

The more widespread is education in a society, the more mystification is required to conceal what is wrong: church, school, and the written word work together for that concealment. This is not the work of a conspiracy; the privileged of society are as much victims of the going mythology as the teachers, priests, and journalists who spread it. All simply do what comes naturally…to say what has always been said, to believe what has always been believed.

In this post-modern world, more than at any other time in history, we are quickly losing any collectively shared sense of what is real, or true, or to be trusted. With our identities shaken to the core, millions of us are searching for leaders or ideologies to revive some sense of meaning, even as a return to racism or misogyny.

In American secular culture (the South and parts of the Midwest aside), religion has long lost its gatekeeping function. It has been replaced by mainstream media, by consumerism, by the culture of celebrity, and – for the upper middle class – by elite educational institutions, especially in the teaching of our national stories. Since cultural and political gatekeeping no longer reaches us through revealed truth, these secular gatekeepers have assumed greater importance. I’ve written several articles about gatekeeping in America:

Gatekeepers, Provocations and Cover-Ups

Howard Zinn and the Academic Gatekeepers

Zero Dark Thirty is a CIA Recruitment Film

For a long time we’ve known – or should have known – that all politicians lie. But we need to pursue that statement to its antecedents: those politicians went to college, and most of those who have risen to the highest levels (including Trumpus, Ted Cruz, Ron DeSantis, Chuck Schumer, J.D.Vance, Josh Hawley, Mitt Romney, Amy Klobuchar, Kirstin Gillibrand, Elise Stefanik and Tom Cotton) attended Ivy League institutions.

America’s elite universities have served, consciously or not, to maintain the mythology of American innocence, good intentions and exceptionalism (which necessarily involves faith in white supremacy and imperial privilege) since the middle of the 19th century.  So it can be useful to know who taught these people, and who taught their teachers.

So it can be useful to know who taught these people, and who taught their teachers.

Students interested in journalism, politics, public administration, international relations or the more rarified realms of college teaching all enter what Noam Chomsky calls “a system of imposed ignorance” and emerge from the elite universities as the most highly indoctrinated future gatekeepers:

A good education instills in you the intuitive comprehension – it becomes unconscious and reflexive – that you just don’t think certain things…that are threatening to power interests …which ends up with people who really honestly (they aren’t lying) internalize the framework of belief and attitudes of the surrounding power system in the society…you learn that there are certain things it’s not proper to say and there are certain thoughts that are not proper to have. That is the socialization role of elite institutions…

People within them, who don’t adjust to that structure, who don’t accept it and internalize it (you can’t really work with it unless you internalize it, and believe it)…are likely to be weeded out along the way…There are all sorts of filtering devices to get rid of people who are a pain in the neck and think independently. Those of you who have been through college know that the educational system is very highly geared to rewarding conformity and obedience…The elite institutions like, say, Harvard and Princeton and the small upscale colleges, for example, are very much geared to socialization. (In) a place like Harvard, most of what goes on there is teaching manners; how to behave like a member of the upper classes, how to think the right thoughts, and so on.

All historians sift through the historical record and cherry pick the facts that will best buttress their arguments. Again, some gatekeepers are nothing but liars and con men who faithfully serve the powerful. Some of them are honest racists and propagandists for empire. But the most convincing are the ones who have emerged from these institutions as true believers in the myth of American innocence.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Yes, some would still excuse men such as Thomas Jefferson who never freed their slaves as “men of their times”, men who were so blinded by their prejudices that they simply did not know any better. Ta-Nehisi Coates, however, writes that even Jefferson’s cousin John Randolph did so, and

…In the two decades after the Revolutionary War, so many planters freed slaves that the proportion of free blacks in Virginia increased from less than one percent in 1782 to 13.5 percent in 1810…The notion that Jefferson was merely following the crowd, and that everyone else did the same thing is convenient for us.

At some point a historian must – or ought to – look deeper. Let’s dispense with the excuse that men didn’t know better. If they didn’t, it was because of their own moral failure. Ten of the first twelve presidents (and two others) were slave owners, as were 27 Supreme Court Justices. These men knew precisely what they were doing, and how they were profiting. And they surrounded themselves with other men who were smart enough to articulate justifications for their actions – and teach them to following generations.

How did the leadership of the exceptional nation that had only recently proclaimed that all men are created equal justify themselves? The French philosopher Montesquieu explained:

It is impossible for us to suppose these creatures (Blacks) to be men, because, allowing them to be men, a suspicion would follow that we ourselves are not Christian.

Slavery was big business. Most early American fortunes were derived at least partially from it, and most 18th-century intellectuals (with many exceptions) grew up taking it, or at least the assumptions of white supremacy, for granted.

Religious authorities were still the primary gatekeepers. But in Colonial America this necessarily had to do with race. Two of the period’s most influential preachers, associated with the First “Great Awakening”, Jonathan Edwards (also a President of Princeton) and George Whitefield, owned slaves. In the South, preachers (including college professor and Woodrow Wilson’s father) J.R. Wilson continued to justify slavery during the Civil War and for decades afterwards.  Pastor Thornton Stringfellow wrote that slavery “…was incorporated into the only National Constitution which ever emanated from God”.

Pastor Thornton Stringfellow wrote that slavery “…was incorporated into the only National Constitution which ever emanated from God”.

Sociologist Orlando Patterson writes that well into the 20th century, “The cross – Christianity’s central symbol of Christ’s sacrificial death – became identified with the crucifixion of the Negro.” Clergymen presided over many lynchings from 1880 onwards, and perhaps 40,000 of them joined the resurgent Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. White supremacy was inseparable from Southern religion, wrote theologian James Sellers; therefore, all threats to it took on mythic importance:

Segregation is a system of belief…It therefore becomes a holy path, complete with commandments, priests, theologians…

Psychologist Joel Kovel asserts that there are two kinds of racism. One is the obvious dominative racism that developed in close contact (including the privilege of rape) between master and slave. The second – aversive racism – arose from Puritan associations of blackness with filth, and it was strongest in the North. In the 1820s the French visitor Alexis De Tocqueville noticed that

Prejudice appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.

The two colonies with the strongest religious foundations – Massachusetts and Pennsylvania – were the first to outlaw “miscegenation.” Five early presidents of Harvard owned slaves, and the University is only recently beginning to admit how much it profited from slavery.

For the entire 19th century, Ivy league professors were among the gatekeepers of the Northern consensus on race. Since that time, elite educational establishments have maintained that essentially religious function: preventing, or at least marginalizing, heresy. They especially target those tasked with maintaining our sense of identity through construction of memory: the professional historians and those they mentor who go on to become teachers themselves. To understand how we got to this point, we’ll need to look at the history of history in America.

Part Two

No other democratic nation revels so blatantly in such self-deceptive innocence, such self-paralyzing reluctance to confront the night-side of its own history. – Cornell West

Why is it that, in a land founded on the secular belief that “all men are created equal,” we are so obsessed with the need to find a scientific basis for human inequality? – Orlando Patterson

Philosophers were hired by the comfortable classes to prove everything is all right. – Brooks Adams

Antebellum college textbooks reflected regional prejudices. Some published in the North questioned slavery, even though Early American History (1841) by Yale’s Noah Webster, often considered the first American history textbook, mentions no African Americans. Southern historians such as William Simms and Thomas Dew (President of The College of William and Mary) published pro-slavery histories.

Other issues claimed people’s attention in the late 1840’s. One was spreading the gospel of enlightened Anglo-Saxon republicanism to Mexico and the western part of the continent through invasion and conquest. Hampton Sides writes:

At universities across the country, the youth had become smitten with the notion of American exceptionalism, and…a fashionable campus craze called the Young America Movement, which, among other things, advocated westward expansion. Even the country’s literary elite seemed to buy into Manifest Destiny. Herman Melville declared that “America can hardly be said to have any western bound but the ocean that washes Asia.” Walt Whitman thought that Mexico must be taught a “vigorous lesson”.

Other intellectuals who supported the movement were William Cullen Bryant, George Bancroft, George Evans, Edwin De Leon and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

After the Civil War, white people everywhere were forced to confront the fearful notion that black people could be voting citizens, theoretically equal to themselves. It was a time of deep insecurity about notions of race and identity (not unlike the present), and university teachers could no longer ignore these issues. But they could certainly channel the discussion into very narrow confines of opinion acceptable to the elites.

One of the privileges of “men of their times” is that they don’t need to be consistent. Consider popular historian Francis Parkman, who claimed that the conquest and displacement of Native Americans represented a triumph of civilization over savagery. Their “own ferocity and intractable indolence” had caused their demise. Apparently, Parkman didn’t notice that he’d confused two opposite traits, because both aggression and laziness were sins in the eyes of his Puritan ancestors, and “othering” does not have to be logical, even for upper-class academics. Much later, Martin Luther King Jr would correct the record:

Generally we think of white supremacist views as having their origins with the unlettered, underprivileged, poorer-class whites. But the social obstetricians who presided at the birth of racist views in our country were from the aristocracy: rich merchants, influential clergyman, men of medical science, historians and political scientists from some of the leading universities of the nation. With such a distinguished company of the elite working so assiduously to disseminate racist views, what was there to inspire poor, illiterate, unskilled white farmers to think otherwise?

Nell Irvin Painter, in The History of White People, lists many 19th-century American intellectuals who spread pseudo-scientific justifications of imperialism, manifest destiny and white supremacy.

The list begins with Ralph Waldo Emerson and includes anthropologists Samuel Morton (Pennsylvania Medical College), Daniel Brinton (U. Pennsylvania), John Burgess (Columbia), George Gliddon and Louis Agassiz (Harvard); ethnologist Henry Schoolcraft; paleontologists Edward Cope and Nathaniel Shaler (Dean of Sciences at Harvard); economists William Ripley (Columbia) and Francis Walker (President of M.I.T.); sociologists George Fitzhugh and Edward Ross (President of the American Sociological Association); political scientist Francis Giddings; philosopher John Fiske (Harvard); historians Henry Adams (Harvard), Parkman (Harvard), Henry Cabot Lodge (Harvard), George Bancroft (Harvard) and two presidents of the American Historical Association (James Rhoades and Theodore Roosevelt).

Physicians seem to have been particularly invested in policing the racial narrative. John Van Evrie wrote books warning against “mongrelization” of the white race. Samuel Cartwright said that the plantation was “converting the African barbarian into a moral, rational and civilized being”. Josiah Nott claimed that “no full-blooded Negro…has ever written a page worthy of being remembered.” James Sims, the father of modern gynecology, did his research on un-anaesthetized Black female slaves.

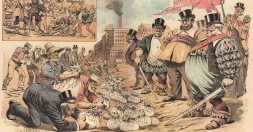

Twisting the idea of natural selection into “scientific racism” and “Social Darwinism,” many intellectuals claimed that America’s wealth proved its virtue, that exploitation and elimination of the weak were natural processes and that unregulated competition resulted in the survival of the fittest.  The next step was to infer that only the affluent were worthy of survival. They were merely restating the Calvinist view of poverty as a condition of the spirit. Life was a harsh, unsatisfying prelude to the afterlife, redeemable only through discipline.

The next step was to infer that only the affluent were worthy of survival. They were merely restating the Calvinist view of poverty as a condition of the spirit. Life was a harsh, unsatisfying prelude to the afterlife, redeemable only through discipline.

Deeply religious people passionately argued that the suffering of the poor was good because it provoked remorse and repentance. A hundred and fifty years later, some academics still claim that giving money to the poor makes them lazier, while giving it to the rich makes them nobler.

William Harper, first president of the University of Chicago, was more candid: “It is all very well to sympathize with the working man, but we get our money from those on the other side, and we can’t afford to offend them.”

Secular apologists, meanwhile, simply substituted “nature” for “God” and used Social Darwinism to justify colonialism. Competition for survival had produced a new human type, the Anglo-Saxon, with the moral sense to accept the White Man’s burden. Such men were uniquely qualified to help civilize those who couldn’t improve themselves without the prolonged tutelage of enlightened colonial rule – or to prevent those (predominantly dark-skinned) people who were inherently stupid from breeding before they sullied the purity of the better races.

The American eugenics movement included prominent academics such as biologists Paul Popenoe (Stanford), Charles Davenport (Harvard) and Harry Laughlin; geologist Henry Osborn (Princeton); psychologists Carl Brigham (Princeton), Henry Goddard, William Sadler, Thomas Bailey, Hugo Munsterberg (Harvard), Elmer Southard (Harvard) and Robert Yerkes (Radcliffe); biologist Charles Davenport (Harvard); theologian Oscar McCulloch; historians Lothrop Stoddard, Carleton Coon (Harvard) and William McDougall (Harvard); economist Irving Fisher (Yale); doctors John Kellogg and Clarence Gamble; lawyer Prescott Hall; sociologist Richard Dugdale; theologian Joseph Fletcher (Yale); conservationists Charles Goethe, Gifford Pinchot (Yale) and Madison Grant; philanthropist E.S. Gosney; botanist (and President of Stanford) David Starr Jordan; and Charles Eliot (President of Harvard). Physicist William Shockley (M.I.T.) revived this nonsense in the 1960s, and Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein (both of Harvard) proposed connections between race and intelligence well into in the 1990s.

Other Eugenics proponents included Luther Burbank, Calvin Coolidge, Daniel Gilman (Yale), John D. Rockefeller, Jr (Brown U.), Alexander Graham Bell, Wickliffe Draper (Harvard),  Oliver Wendell Holmes (Harvard), W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Margaret Sanger, Nikola Tesla, Robert Graham (who created a “Nobel sperm bank” in 1980) and, of course, the Nazis, whose forced sterilization program was partly inspired by that of California.

Oliver Wendell Holmes (Harvard), W.E.B. DuBois, Marcus Garvey, Margaret Sanger, Nikola Tesla, Robert Graham (who created a “Nobel sperm bank” in 1980) and, of course, the Nazis, whose forced sterilization program was partly inspired by that of California.

But let’s take a brief detour and discuss public education. John Gatto, former New York State “Teacher of the Year”, writes:

We don’t need Karl Marx’s conception of a grand warfare between the classes to see that it is in the interest of complex management, economic or political, to dumb people down, to demoralize them, to divide them from one another, and to discard them if they don’t conform…you needn’t have studied marketing to know that there are two groups of people who can always be convinced to consume more than they need to: addicts and children. School has done a pretty good job of turning our children into addicts, but it has done a spectacular job of turning our children into children.

Much later, millions of us are really dumb – or to be generous, profoundly misinformed – despite our educational system. Or, we must ask, is it because of this system? In Chapter Five of my book I compare indigenous initiation traditions to mandatory – that is, forced – public education and refer to Gatto’s book Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. The Social Darwinists and eugenicists who designed America’s educational system modeled it on that of the militaristic Prussian state. Since then, seven generations have endured a routine designed to restrain dissent and originality and reduce everyone to a uniform, standardized level. Gatto asks, “Could it be that our schools are designed to make sure that not one (child) ever really grows up?”

By the 1890s, many were demanding schoolbooks that would bind the nation together, while minimizing sectional differences. For Confederate veterans, reconciliation meant a reunion of whites across regional lines while rejecting both racial equality and a strong central government that would enforce civil rights. Mainstream publishers responded to the southern market, minimizing discussion of slavery.

As public education evolved, it had two specific goals: (1) to make and keep the young only as literate and skilled as necessary for an evolving capitalist economy and (2) to teach political loyalty in a time when religion was being replaced by nationalism. Duke historian William Laprade candidly acknowledged that the function of history in the schools was “the inculcation of a species of patriotic religion.” Ellwood Cubberley, Dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education from 1917 until 1933, wrote:

Our schools are…factories in which the raw products (children) are to be shaped and fashioned…And it is the business of the school to build its pupils according to the specifications laid down.

Much later, James Loewen wrote:

Textbook authors need not concern themselves unduly with what actually happened in history, since publishers use patriotism, rather than scholarship, to sell their books…the requirement to take American History originated as part of a nationalist flag-waving campaign early in the (20th) century…Many history teachers don’t know much history: a national survey of 257 teachers in 1990 revealed that 13% had never taken a single college history course…

The situation might well be worse if they had taken university history courses, as we’ll see. Despite stereotypes of the 1960s, the more educated a person is, the more likely they are to support America’s imperial wars.

Quoting from early texts, Gatto distills schooling’s intent into six functions:

1 – Adjusting: establishing fixed habits of reaction to authority to preclude critical judgment.

2 – Integrating: making people as alike as possible.

3 – Diagnosing: determining everyone’s proper social role.

4 – Differentiating: sorting children by role and training them “only so far as their destination in the social machine permits.”

5 – Selecting: identifying the unfit at an early age.

6 – The propaedeutic function: teaching a minority to manage the rest, who are “deliberately dumbed down and declawed…”

Public schooling taught children to exchange obedience for favors and advantages. It was never intended to create citizens, but servile laborers and consumers. After a few generations it left children vulnerable to marketing, which ensured that they would grow older but never grow up. And it reversed the age-old tradition of identifying a child’s unique gifts. By the 1950s an unexpected bi-product would be an epidemic of illiteracy.

In 1909, Wilson, then president of Princeton (which would refuse to admit black undergraduates for another forty years), told teachers,

We want one class of persons to have a liberal education, and we want another class…a very much larger class…to forgo the privilege…

From that point (when the system was installed universally), literacy began to decline from nearly 100% to a point when, in 1973, functional illiteracy kept 27% of men from military service. Now, claims Gatto, “40% of blacks and 17% of whites can’t read at all.” At one end of the spectrum, 45 million adults are functionally illiterate, and at the other, 42% of college students never read a book after they graduate.

Meanwhile, as a growing Catholic population desired history books that were less steeped in Protestant prejudices, their presses began issuing books for parochial schools. By the 1920s, some large publishers were producing books that were acceptable to Catholics while others were appeasing Southerners.

An exception, An American History (1911) by David Muzzey became a standard text until it came under fire during the 1920s Red Scare when conservatives attacked it as subversive.

In 1925, the Tennessee “Scopes Monkey Trial” highlighted religious attacks on evolution. That state’s Butler Act (not repealed until 1967) banned teaching “any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible.” During that decade, 37 bills were introduced in 20 states to prohibit the teaching of evolution.

Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin which he built with his own hands. – American college student.

You teach a child to read, and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test. – George W. Bush

Students – at all levels – were reading what local gatekeepers wanted them to read, if they could read at all. We’ve all seen statistics about ignorance of basic facts in America.

Part Three

Memory says, “I did that.” Pride replies, “I could not have done that.” Eventually, memory yields. – Frederick Nietzsche

For empires, the past is just another overseas territory ripe for reconstruction, even reinvention. – Alfred McCoy

Let’s return to our main theme, the history of history.

The gatekeepers were succeeding. By 1900 descendants of the Confederate aristocracy were in complete control of the racial narrative, as I write here. Immediately after the war, Edward Pollard’s book The Lost Cause: A New Southern History of the Confederates portrayed the Old South as a multicultural paradise of racial harmony untouched by the evils of industrial capitalism.  It recast the struggle to perpetuate slavery as a noble defense of a traditional way of life, led by gallant gentleman-officers and fought by loyal soldiers in the “War of Northern Aggression”. The fact that tens of thousands had deserted was not included in the story.

It recast the struggle to perpetuate slavery as a noble defense of a traditional way of life, led by gallant gentleman-officers and fought by loyal soldiers in the “War of Northern Aggression”. The fact that tens of thousands had deserted was not included in the story.

Within two generations, most white Americans remembered the war as one “between brothers”, fought over states’ rights rather than slavery. And they believed that blacks hadn’t been ready for freedom because, as one preacher wrote, the former slaves couldn’t “sacrifice their lusts.”

The United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded in 1894) erected some 700 monuments to the Lost Cause, most of them in the 1950s. But their most effective tool was the propaganda they forced into the schools. The primary focus was on insuring that Southern schools used only those history books that defended slavery and praised the Ku Klux Klan, and banned those books that didn’t.

The 1908 History of Virginia claimed, “Generally speaking, the negroes proved a harmless and affectionate race, easily governed, and happy in their condition.” Another textbook, Virginia: History, Government, Geography, used in seventh-grade classrooms into the 1970s (!), claimed, “Life among the Negroes of Virginia in slavery times was generally happy. The Negroes went about in a cheerful manner…” A high school textbook described a slave’s life:

He did not work as hard as the average free laborer since he did not have to worry about losing his job…his food was plentiful, his clothing adequate, his cabin warm, his health protected, his leisure carefree. He did not have to worry about hard times, unemployment, or old age.

How ubiquitous were these texts? Greg Huffman estimates that seventy million students were enrolled in the South’s public elementary and secondary schools for the 80 years between 1889 and 1969. All of them were subjected to this “Born With the Wind” version of history. And they exerted great influence on Northern book publishers as well, who

…had decisions to make if they wanted to sell books to Southern schools. Go all in with Lost Cause dogma and…sell the book only in the South? Or have two versions of the same book – one with…watered-down history for the South, and another one with historical facts for everyone else? The latter was often the choice.

Mississippi’s public schools used Lost Cause textbooks exclusively until a federal court forced them to stop in 1980.

But we have bigger fish to fry. Two social myths – a reunited America with a national purpose and the hugely popular Horatio Alger tales of enterprising young men who prospered without government assistance – were just what the oligarchs of both North and South needed to divide the working classes.

So we need to talk about the teaching of Lost Cause mythology in the North, where most intellectuals accepted the continuation of white supremacy. They learned their trades not in Bible schools but in the most elite institutions. Donald Yacovone surveyed 3,000 textbooks that they wrote and concluded:

For the most part, the textbooks from the pre-Civil War period through the end of the century followed a basic format: They would go from exploration to colonization to revolution to creation of the American republic, and then every succeeding presidential administration. Anything outside of the political narrative was not considered history and was not taught.

But as recently as the 1940s,

…it was astonishing to see positive assessments of slavery in American history textbooks, which taught that the African American’s natural environment was the institution of slavery, where they were cared for from cradle to grave…They dismissed the slave narratives as propaganda, downplayed the history of Africans before slavery, and ignored the work of African American scholars…

Again, much of this deadly nonsense centers around Wilson, the only president with a PhD – in History – and even by the standards of his time, a racist. In 1915 he showed the film Birth of a Nation  in the White House, making it the first mega-hit. Depicting heroic whites rescuing young women from the clutches of their drooling black abductors, it quickly led to a massive resurgence of the KKK. Earlier, Wilson had written of Reconstruction:

in the White House, making it the first mega-hit. Depicting heroic whites rescuing young women from the clutches of their drooling black abductors, it quickly led to a massive resurgence of the KKK. Earlier, Wilson had written of Reconstruction:

…the dominance of an ignorant and inferior race was justly dreaded…The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation – until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the Southern country.

On immigration, he contrasted “the men of the sturdy stocks of the north” with “the more sordid and hopeless elements” of southern Europe, who had “neither skill nor quick intelligence.”

In the matter of Chinese and Japanese coolie immigration, I stand for the national policy of exclusion. We cannot make a homogenous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race.

Two forces contributed to what Peter Novick calls a “racist historiographical consensus” around the turn of the century. One was the nationalism that was quickly replacing religion, even in the South, as a central unifying cultural and political factor. The second was the increase in racism among intellectuals who relied on Social Darwinism and Eugenics to back the concept with the new religion, science.

…professional historians worked to revise previous northern views on several related questions. They became as harshly critical of the abolitionists as they were of “irresponsible agitators” in the contemporary world, they accepted a considerably softened picture of slavery, and they abandoned theories of the “slave power conspiracy.” Above all, they joined whole-heartedly with southerners in denouncing the “criminal outrages” of Reconstruction…

For another forty years, the “Dunning School” dominated the writing of post-Civil War history. To these learned men, black suffrage had been a political blunder. Republican state governments had been corrupt, unrepresentative and oppressive. The revisionist historian Eric Foner condemns this perspective as

…not just an interpretation of history. It was part of the edifice of the Jim Crow System. It was an explanation for and justification of taking the right to vote away from black people on the grounds that they completely abused it during Reconstruction…a justification for the white South resisting outside efforts in changing race relations…helped to freeze the minds of the white South in resistance to any change whatsoever…historians have a lot to answer for in helping to propagate a racist system in this country.

William Dunning headed both the American Historical Association and the American Political Science Association and edited their journals. At Columbia, he directed much graduate work in U.S. history, teaching that blacks were incapable of self-government, that the North’s greatest sin consisted of relinquishing control of the Southern governments to “ignorant, half-civilized former slaves (who) had…no aspiration or ideals save to be like whites.” His influence was enormous.

His student Ulrich Phillips taught at Tulane, Michigan and Yale, critiquing slavery (inaccurately) as an unprofitable economic system, but one that had value in civilizing “savage Africans”. His books remained the standard texts on slavery for decades. John Burgess, who taught at Columbia, wrote that “a black skin means membership in a race of men which has never of itself succeeded in subjecting passion to reason.” George Beer (Columbia) wrote that “the negro race has hitherto shown no capacity for progressive development except under the tutelage of other peoples.” Other members of the school included James Garner (U. Illinois), William Davis (U. Kansas), J. G. Hamilton (U. North Carolina), Walter Fleming (chair in history at Vanderbilt), Charles Ramsdell (U. Texas), Mildred Thompson (History Chair at Vassar), the Holocaust denier Harry Barnes (Smith College) and Ellis Oberholzer (U. Pennsylvania), who claimed that Yankees didn’t understand slavery because they “had never seen a nigger except Fred Douglass…Blacks were as credulous as children, which in intellect they in many ways resembled.”

Avery Craven (Harvard) took pro-slavery positions. Milo Quaife (U. Chicago) derided the “absurd doctrine of racial equality.” Ellis Coulter, who taught at Georgia for sixty years, founded the Southern Historical Association and edited the Georgia Historical Quarterly for fifty years, pontificated:

…most of the Negroes (would) spend their last piece of money for a drink of whisky…Black participation in government was a diabolical development, to be remembered, shuddered at, and execrated.

But the gatekeeping didn’t end with unrepentant racists. Henry Commager (Columbia) and Samuel Morison’s (Harvard) The Growth of the American Republic, read by generations of college freshmen, claimed that slaves “suffered less than any other class in the South…The majority…were apparently happy.” Such respected Anglo-Saxon eminences could produce high school-level prose without ever being questioned. In The Founding of Harvard College, Morison wrote: “They (the Puritans) were a free and happy people”. Many years later, Howard Zinn would observe that such “sloppy generalizations…contribute to the common glorification of this country’s early years…feed arrogance and dull the critical faculties…”

Arthur Schlesinger Sr (Harvard), suggested that high achievement among some blacks could only be the result of an “infusion of white blood.” Seymour Lipset (Harvard) wrote, “America has been a universalistic culture, slavery and the black situation apart.” Jon Meacham, Editor-in-Chief of Newsweek, received the Pulitzer Prize for his biography of Andrew Jackson, which covers the Trail of Tears in four paragraphs. Arthur Schlesinger Jr (Harvard) also won the Pulitzer for The Age of Jackson without mentioning it at all.

Of course, there were occasional exceptions. Harold Rugg’s high school social studies textbook series traced the evolution of American democracy in the face of pervasive social problems. But conservatives attacked it as subversive, and by the early 1940s it was removed from schools.

Part Four

This crap should not be accepted for any credit by the state…a “terrible anti-American academic. – Mitch Daniels, President of Purdue University, on Howard Zinn

It’s not an unbiased account. So what? If you look at history from the perspective of the slaughtered and mutilated, it’s a different story. – Howard Zinn

You’ve got to graduate from an Ivy League university and read all the latest reports from the most esteemed think tanks to get smart enough to understand why it’s a good idea to fight Russia and China at the same time. – Caitlin Johnstone

The overwhelming majority of information is classified to protect political security, not national security. – Julian Assange

Academics also directed the narrative of American imperialism, one of our most deeply held stories about ourselves, how the nation never starts wars but only fights to aid deserving people. Seven generations of schoolchildren have learned that the nation of extreme individualism is an individual among nations, the exceptional one, chosen by Divine Providence to redeem the world. If we were honest with ourselves, most of us – at least most whites – would still admit some adherence to this story, of which World War Two is our most shining example, and which still drives our support for sanctions, coups and direct military intervention in Ukraine, China, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, Nicaragua and countless other places.

To those outside our mythic bubble, however, this is a story that we regularly need to tell ourselves, to still our doubts that our long-distance murder and denial of self-determination to other people have moral meaning. This helps explain why our gatekeepers – historians and journalists – speak with nearly one voice (as they do now, concerning Julian Assange, Chelsea Manning and other whistle blowers) to condemn anyone who might question our stories, regardless of their popularity or stature in their profession. American myth is highly unstable and questioning any particular aspect of it can lead to skepticism about all of it.

Historians claim to be objective, even scientific. Yet during World War One, historians in all the combatant countries eagerly endorsed the war effort and wrote books proclaiming the essential goodness of their own sides. In the U.S. the first university survey courses on the history of Western civilization taught that America was fighting to defend the progressive values supposedly embodied in British and French history and contradicted by German universities, and most certainly by socialism.

Immediately after the war, the U.S. and twelve other nations attacked the Soviet Union in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent consolidation of communist rule. Afterwards, compliant intellectuals inverted history; Yale historian John Gaddis terms this invasion a “defensive” action.

Between the wars, writes Novick, the old guard of increasingly insecure Protestant historians expressed widespread anti-Semitism. One professor regularly warned Jewish graduate students that “History belongs to the Anglo-Saxons. You belong in economics or sociology.”

Letters of recommendation repeatedly tried to reassure prospective employers on this point: Oscar Handlin “has none of the offensive traits which some people associate with his race,” and Bert Loewenberg “by temperament and spirit…measures up to the whitest Gentile I know”…Daniel Boorstin “is a Jew, though not the kind to which one takes exception”, and Richard Leopold was “of course a Jew, but since he is a Princeton graduate, you may be reasonably certain that he is not of the offensive type”…Solomon Katz was “quite un-Jewish, if one considers the undesirable side of the race”.

Since World War Two is closer in memory, academic Gatekeepers still insist on controlling the narrative, both of how we got into it and how we got out. This is the myth of the Good War.

The social function of myth is to validate the social order. At this level of understanding, myth equals ideology plus narrative. Stories help us digest the ideology. Myths determine perception, like the lenses of a pair of glasses. They are not what we see, but what we see with. We can’t see outside our bubble (but outsiders can see us.) We give our attention to one set of possibilities rather than another, and our intentions and dreams follow. So, myth creates fact. Indeed, myth trumps fact.

We draw stories from our past and abstract them into evocative icons (the Alamo, Pearl Harbor) that contain the essential elements of our worldview. So obvious that they never have to be “explained”, they transform history into sacred legends that describe reality to us and prescribe our choices and behavior within acceptable limits. “Myth,” writes Richard Slotkin, “is history successfully disguised as archetype.”

Curiously, if we add Custer’s Last Stand, the sinking of The Maine and 9-11 and to that list, we find that most of those iconic images are of our most famous defeats. On one level, this reflects the complex interweaving between the American Hero (or winner) and his shadow, the victim (or loser), that our mythology has been dreaming for four hundred years. The innocent nation, once again, finds itself victimized, under attack by evil men, with dark skins. Since, as G. W. Bush said, they hate us for our freedoms, we are justified in responding with Biblical ferocity, as we did to the Japanese – the racialized Other – much more so than to the Germans.

From the very beginning, history and myth intersect throughout the story of America, and it’s almost impossible to tease out the differences. But let’s be clear about this: we’re not simply talking about lies, distortions, omissions and propaganda. That’s “myth” in the lesser meaning of the term. We are talking about why we frame our stories about ourselves in the way we do, and why we are – increasingly – desperate to believe them, to use them to re-stabilize the crumbling building blocks of our collective self-image.

Franklin Roosevelt had decided by 1940 on the necessity of defeating Germany. But to overcome strong anti-war sentiment he needed to lure the Japanese (whose codes had been broken and whose exact intentions were well known) into attacking Pearl Harbor, after which treaty obligations would force the Germans to declare war on the U.S.

But every American has been taught that America suffered a surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, was drawn into the war reluctantly and then proceeded to save the world from evil. This scenario of only fighting when provoked is a bedrock aspect of our national mythology. It provides the essential energy of disillusioned innocence – why would they attack us? – that has propelled the nation into every war since the invasion of Mexico.

Historians have long been charged with maintaining this narrative – and ostracizing those who question it. To really understand what the gatekeepers can do, consider Charles Beard.

Beard, like Dunning before him, served as president of both the American Historical Association and the American Political Science Association. Historian and retired military officer Andrew Bacevich writes:

…Beard stood alone at the pinnacle of his profession. As a historian and public intellectual, he was prolific, influential, fiercely independent, and equally adept at writing for scholarly audiences or for the general public.

In 1947 the National Institute of Arts and Letters awarded him their gold medal for the best historical work of the preceding decade. But that same year he published President Roosevelt and the Coming of the War, which accused FDR of lying to the nation. He also revealed (in “Who’s to Write the History of the War?”) that the Rockefeller Foundation had subsidized an official history of how the war had come about. Yes, writes Gary North,

…the victors always write the history books, but when the historians are actually policy-setting participants in the war, the words “court history” take on new meaning.

Indeed, some of those who did write such histories attained high government positions, and many of them, including Samuel Morison, savagely attacked Beard as at best an “isolationist” and at worst a senile old fool. They quickly and permanently destroyed his reputation because he had committed the grave sin of questioning their heroic “Good War” narrative, or in current terms, of promoting a conspiracy theory. Beard died in 1949. His book on Roosevelt quickly went out of print and was not reprinted until 2003. Today the public has forgotten him. Within the profession, however, Beard remains a reviled and discredited figure. North writes:

This is why there are no tenured World War II revisionists who write in this still-taboo and well-policed field. The guild screened them out, beginning in the early 1950′s…What the guild did to…Beard (and others) posted a warning sign: Dead End.

For more detail on how Roosevelt provoked the attack on Pearl Harbor, see Robert Stinnett’s Day of Deceit.

The other half of the “Greatest Generation” myth conveyed by most historians is how the nation avoided a costly invasion of Japan and ended the war with the atom bomb. However, revisionist writers such as Gar Alperovitz have shown that the U.S. didn’t need to drop the bombs, that the mass atrocities had much more to do with the approaching confrontation with the Soviet Union. Read here, here or here.

The Japanese were ready to surrender and it wasn’t necessary to hit them with that awful thing. – President Dwight Eisenhower

The actual narrative of World War Two is full of accounts of similarly unnecessary, mass atrocities that the Allies committed, and the lies that followed to justify them. Zinn himself gives accounts of two such crimes that he personally participated in as a bombardier: the bombings of Plzen, Czechoslovakia and Royan, France.

Still, most Americans hold to the story that the Exceptional Nation fought the Good War reluctantly  and ended it with humanitarian motives (at least in terms of American lives saved). Bacevich concludes:

and ended it with humanitarian motives (at least in terms of American lives saved). Bacevich concludes:

Present-day Americans have become so imbued with this narrative as to be oblivious to its existence. Politicians endlessly recount it. Television shows, movies, magazines, and video games affirm it. Members of the public accept it as unquestionably true…Today the Good War narrative survives fully intact. For politicians and pundits eager to explain why it is incumbent upon the United States to lead or to come to the aid of those yearning to be free, it offers an ever-ready reference point…

In that sense, the persistence of the Good War narrative robs Americans of any capacity to think realistically about their nation’s role in the existing world. Instead, it’s always 1938, with appeasement the ultimate sin to be avoided at all costs. Or it’s 1941, when an innocent nation subjected to a dastardly attack from out of the blue is summoned to embark upon a new crusade to smite the evildoers. Or it’s 1945, with history calling upon the United States to remake the world in its own image.

(Or it’s 2022 and liberal Democratic congresspersons unanimously support over $50 billion to extend the war in Ukraine.)

After the war both liberal and conservative historians encouraged an overwhelmingly affirmative and celebratory stance toward the American experience, in three basic themes. The first was nearly-universal justification of the cold war and the development of government-supported social science research which assumed that the nation’s foreign policy was identical with the promotion of peace and freedom.

And this could still arrive along with sloppy writing and generalization. Ernest May (Harvard), who had prepared a confidential study of strategic arms buildups and would later advise the 9/11 Commission, wrote of the Spanish-American War: “American public opinion had frenziedly demanded war.” Zinn responded that in 1898 “…there were no ways of testing general public opinion…the frenzy was mostly the fulminating of a few very important newspapers.” Is this a silly example? Only if we don’t realize that May was really offering a historian’s rationale for current warmongering:

Such a generalization obscures the way decisions for war are made by a handful of men at the top, and the way public opinion is manipulated…to build support for it.

The second was specialization and escape into trivia. Zinn criticized 1960s academics who held such:

…cluster of beliefs…roughly expressed by the phrases “disinterested scholarship”… ”dispassionate learning”…”objective study”…”scientific method” – all adding up to the fear that using our intelligence to further our moral ends is somehow improper…Knowledge can also serve the purposes of social stability in another way – by being squandered on trivia. Thus the university becomes a playpen in which the society invites its favored children to play – and gives them toys and prizes, to keep them out of trouble…The larger interests are internalized in the motivations of the scholar: promotion, tenure, higher salaries, prestige – all of which are best secured by innovating in prescribed directions…There is no question, then, of a disinterested” community of scholars, only a question about what interests scholars serve.

This reinforced the third theme. Many academics were still colluding in the nation’s refusal to address its original sin of racism. Zinn discovered that

From 1960-1966…of 3,265 dissertations in modern history, eighteen dealt with this problem (race)…Of 446 articles in The American Historical Review from 1945 to 1968, five dealt with the Negro question.

The Daughters of the American Revolution helped blacklist 170 textbooks that did not sufficiently reflect Christian and anticommunist values. African American history remained on the margins of academic scholarship, and blacks were excluded from teaching positions at most universities. Meanwhile, many of the “best and the brightest” academics, including the future war criminal Henry Kissinger, entered the revolving door circuit between academia, media, business and government. Novick writes:

“Intellect has associated itself with power as perhaps never before in history,” Lionel Trilling observed in 1952. With the exceptions of physics, it would be difficult to think of any academic discipline which, during World War II and the cold war, participated more wholeheartedly in that association than did history…There was, in fact, criticism within the CIA concerning what some considered the overrepresentation of historians within its ranks.

After the 1960s the culture wars began in earnest. In 1974 local schools in Kanawha County, West Virginia adopted new textbooks and works by Eldridge Cleaver, Arthur Miller and George Orwell. Opponents firebombed school buildings, shot up buses, beat journalists and shut down the school system.

On campuses the 1960s had seen a new generation of politically active historians including Jesse Lemisch, Herbert Apthecker, William Appleman Williams and Staughton Lynd. They collectively promoted “history from the bottom up”, a more inclusive and comprehensive formulation that brought all subjects, especially blacks and women, more fully into the discipline. It was an explicit challenge to the elitist and insular traditions of historical writing within the academy, and more specifically to the deadening “consensus” approach to the American past that had grown out of the repressive atmosphere of the Cold War. Zinn’s People’s History of the United States followed in 1980.

Centrist historians ignored most of these radicals. For example, a recent introduction to historiography (the writing of history) mentions Lemisch once, and Chomsky (not a historian but certainly a major world intellectual on historical issues) not at all. Nor does it address the question of political bias in the profession. It does mention Beard, but not his marginalization. An online list of 269 “Famous American Historians” doesn’t mention Zinn, Chomsky, Lemisch or Lynd.

However, as with Beard, the gatekeepers really couldn’t ignore Zinn. And twelve years after his death, they still can’t. Why? After the turbulence of the sixties and disillusionment of the seventies, people were hungry for history that acknowledged what they could see with their own eyes. Millions now knew how the nation had raped Viet Nam and countless other nations, and they wanted context. Forty-two years after its publication, A People’s History has exceeded 3.6 million copies in the U.S. edition alone. And, where the book burners haven’t fully established their restrictions, over 100,000 teachers have registered with the Zinn Education Project.

Gatekeeper criticisms of Zinn tend toward two common themes:

1 – He was too left-wing for decent academics. The sole mention of him on the History Today website attacks People’s History with this gem:

Among the (otherwise entirely noble) contributors are several known Communist agents, a pederast, a terrorist and two men involved in a bloody prison revolt.

2 – While Zinn was acceptable for idealistic teenagers, wrote Jill Lepore (Harvard), he was not (like them) a serious scholar. He was not objective or dispassionate. Worst of all, he was “politicized” and had “contempt for society’s elites”. David Greenberg (Yale) sniffs:

Zinn was in effect saying that Big-Time History – with its formidable air of authority, its footnotes and archival documentation, its vetting by communities of expert scholars—had really just served to shore up the power of established elites and put down stirrings of protest.

Well, yeah…Clement Lime responds:

David Greenberg doesn’t hate Howard Zinn because he was a bad scholar, but because he was a radical…Most historians, as educated and privileged offspring of the middle class, are ideologically invested in a liberal ideal of America as a place where various groups…negotiated their differences through a clash of forces that produced some reasonable outcome, and for many this becomes the only way to tell the story.

Zinn responded to the inquisitors:

Holding certain fundamental values does not require that historians find certain desirable answers in the past, it just turns their attention to certain useful questions.

It was perhaps a matter of timing. Zinn opened the door in ways that earlier revisionists had not. Since A People’s History, dozens of excellent histories written “from the ground up” have appeared, both within academia and without, even if few of their authors have attained anywhere near the influence and old school reputations of their elders. Proud that Zinn blurbed my book, I’ve written about his accusers here. And he wrote plays also:

They are all proclaiming that my ideas are dead! It’s nothing new. These clowns have been saying this for more than a hundred years. Don’t you wonder: why is it necessary to declare me dead again and again? – Zinn, as Karl Marx, in “Marx in Soho”

Chico Marx put it even more plainly:

Who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes?