Part One

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori. – It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country. – Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace)

If any question why we died, tell them, because our fathers lied. – Rudyard Kipling

So if you love your Uncle Sam

Bring them home, bring them home

Support our boys in Vietnam

Bring them home, bring them home – Pete Seeger

My good sir, what are you doing? Don’t you know the armistice goes into effect at 11:00 o’clock? – German officer under a white flag, to American officer

We’ll be back in twenty years. – Another German officer

Veterans Day was established in 1954 to celebrate all U.S. military veterans. In our modern memory, however, it has lost its connection with its original name, Armistice Day, which marks the anniversary of the end of World War I in 1918 and is still observed as such in Belgium, France, Brittan and many other countries. In 1938 Congress had made Armistice Day a holiday explicitly dedicated to perpetuating world peace. The shift from that stance to one praising those who fight, taken during the Cold War, should tell us much about the American psyche and the American empire. And an honest look at why so many died for so little might just compel us to consider renaming this holiday once again.

We cannot imagine the extent of the suffering. The Western Front stretched from Switzerland to the North Sea. Casualties on both sides averaged 2,250 dead and almost 5,000 wounded every day. Over four years, 3,250,000 were killed and 7,750,000 were wounded there. Total losses – including the Eastern Front, the Balkans, Austria, Italy, Turkey, the Middle East and Africa – were 8,400,000 dead and 21,400,000 wounded (of which seven million were permanently maimed), bringing total casualties to almost thirty million. Another 6,300,000 civilian deaths were attributed to the war. Then, the Spanish Flu, spreading before the end of the war and certainly exacerbated by it, killed an additional 25-50 million people.

Some soldiers refused to fight. Of 112 French divisions, 68 had mutinies. Fifty men were shot by firing squads. Three of those executions became the basis for Stanley Kubrick’s antiwar masterpiece, Paths of Glory, in which a pompous general castigates his soldiers for retreating and talks of “patriotism.” Kirk Douglas, the officer who defends his men, enrages the general by quoting Samuel Johnson: “Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.”

This essay is about that last day of the war – actually, it’s about the last six hours. After arguing for three days, emissaries of the belligerents signed the armistice document at 5:00 AM on November 11th, agreeing that fighting on the Western Front would formally end at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. That left six hours, during which all the French and British generals and most of the Americans insisted on advancing everywhere, taking as much ground as possible (even though the armistice clearly demarcated what the new boundaries would be) and punishing the Germans until the very last moment.

I was reminded – brutally – of what happened during those last hours when I viewed Netflix’s new production of All Quiet on the Western Front. The new film departs from both Erich Maria Remarque’s book and the classic 1930 film in two significant ways:

new production of All Quiet on the Western Front. The new film departs from both Erich Maria Remarque’s book and the classic 1930 film in two significant ways:

1 – Most of the story takes place during the last three days of the war, regularly cutting back and forth between the ongoing carnage suffered by 18-year-olds in the trenches and the well-dressed, well fed diplomats and generals negotiating the precise terms of the armistice document in a finely-furnished rail car. It’s a clear contrast and an indictment of the old men who always send young men to sacrifice themselves.

2 – It depicts certain German generals as being so humiliated by the terms of the armistice and the personal loss of honor that, unwilling to surrender, they order a final, bloody attack on the allies. It ends with the protagonist dying, not from a sniper’s bullet on an “all quiet” morning (as in the 1930 film), but from wounds he suffers in those final, frenzied moments.

Both the original film and this new one are deeply anti-war and should be required viewing for all high school students. But any film presents a narrative with a point of view, and I was bothered by this one, because those last scenes invert history. It wasn’t the authoritarian Germans who flung thousands of boys at massed machine guns and artillery, knowing full well that the armistice had already been signed. It was the democratic French, British and Americans.

Hostilities on the Eastern Front had ended months before. Everyone was hearing rumors that the German Kaiser had abdicated and left the country, that Germany had become a republic, that Berlin was already a scene of revolutionary riots. German artillery had fallen silent in many places, only firing in response to Allied artillery. Some German troops were retreating toward home. Several units had mutinied. Over ten thousand had surrendered in the last week.

But the Allied generals insisted on more artillery bombardments and yet more mass infantry attacks, often uphill, over open ground – against entrenched machine guns – that should not stop until precisely 11:00 AM. They threatened to court martial any field commanders who might consider the humane decision to disobey, avoid any useless casualties and keep their men in the trenches until the shooting stopped. A few did just that, risking their careers, but the commanders of nine of the sixteen American divisions obeyed, sending their men forward. Some of the attacks began as late as 10:00 AM, and some units who had not heard the ceasefire order kept fighting (and dying) until 4:00 PM.

According to the most conservative estimates, during those last hours following the signing of the armistice, all sides on the Western Front suffered over 2,700 deaths (including at least 320 Americans) and 11,000 total casualties, 10% more than would occur on D-Day, 26 years later. “There was, however,” writes Joseph Persico, “a vast difference”:

The men storming the Normandy beaches were fighting for victory. Men dying on Armistice Day were fighting in a war already decided.

Why the mad, final advance and utterly unnecessary slaughter on 11/11/11? There seem to be two obvious themes here, and a third that requires a greater imagination of us.

The first is simple, understandable vindictiveness and the desire for maximum vengeance on the part of the French, whose farms, towns, forests and cities had been churned up for four years, and whose people had died in the millions.

The second, regrettably, was a final opportunity for glory and the possibility of career advancement. Accounts written by many of the senior officers such as Douglas MacArthur and George Patton make this quite clear. Patton, at least, was honest about his martial vocation:

We can but hope that e’re we drown

‘Neath treacle floods of grace,

The tuneless horns of mighty Mars

Once more shall rouse the Race.

When such times come, Oh! God of War

Grant that we pass midst strife,

Knowing once more the whitehot joy

Of taking human life.

We need to go deeper.

Part Two

You can’t stop me. I spend 30,000 men a month. – Napoleon

I would rather have a dead son than a disobedient one. – Martin Luther

¡Que viva la muerte! – Francisco Franco

Yes, the desire for vengeance and the hope of glory and promotion are two convincing explanations for why commanders would override their natural, paternal concern for the men under their command. But these answers don’t go far enough to satisfy me. After all, this was world war, and the carnage had not relented (except for the first Christmas) for four years.

Old men had been making these decisions and – maybe more of a mystery – young men had been obeying them with few exceptions all this time. Neither economics nor religion nor dialectical materialism nor even psychology can explain the source, the intensity and the mutual culpability of this madness. Only mythological thinking can get us to the core.

My book Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence attempts to understand the enduring power of the foundational myth underlying all Western culture, the narrative of the killing of the children. This story is first articulated in Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son Isaac to prove his loyalty to God in the tale known as the Aqidah.  It then moves through the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross and blossoms in the twenty centuries of abuse, betrayal and the profound depression – or unquenchable desire for vengeance – that characterize modern history and modern families. Most specifically, it provides a template for every ensuing generation of young men who, desperately but unconsciously seeking to die to their boyhoods and be reborn as men, go willingly to the literal death that older men have planned for them. It is about powerful but uninitiated men indoctrinating uninitiated, powerless men into the worship of a vengeful god, and later of his substitute, the national state.

It then moves through the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross and blossoms in the twenty centuries of abuse, betrayal and the profound depression – or unquenchable desire for vengeance – that characterize modern history and modern families. Most specifically, it provides a template for every ensuing generation of young men who, desperately but unconsciously seeking to die to their boyhoods and be reborn as men, go willingly to the literal death that older men have planned for them. It is about powerful but uninitiated men indoctrinating uninitiated, powerless men into the worship of a vengeful god, and later of his substitute, the national state.

These stories are absolutely central to Western consciousness. They show us how long it has been since initiation rituals broke down. For at least three millennia, patriarchs have conducted pseudo-initiations, feeding their sons into the infinite maw of literalized violence. Indeed, it was their great genius – and primordial crime – to extend child-sacrifice from the family to the state. Boys eventually were forced to participate in the sacrifice. No longer comprehending the idea of surrender to a symbolic death, they learned to, in a sense, overcome death by inflicting it on others, to kill for some great, transpersonal cause or ideology.

Ultimately dying for the cause became a more meaningful act than to kill for it. Within the suffocating confines of monotheism and patriarchy, martyrdom became an ethical virtue that every believer must be prepared to emulate. “Uniquely among the religions of the world,” writes Bruce Chilton,

…the three that center on Abraham have made the willingness to offer the lives of children – an action they all symbolize with versions of the Aqedah – a central virtue for the faithful as a whole.

By the late 19th century, with nationalism replacing religion as a central unifying factor, the sky gods of Greek myth, Ouranos and his son Kronos came to rule the unconscious of modern man. For three or four generations, as Robert Bly taught, relations between fathers and sons had been changing fundamentally when men left their homes and farms for the factories. Fathers became absent fathers, and sons found themselves without close role models – just as the entire Western world was becoming subject to the most rapid technological changes in history. It was a period comparable only to our own.

One Frenchman (who was fated to die in the first weeks of the Great War) wrote that the world had changed more since he had been in school than it had since the Romans. In the thirty years between 1884 and 1914, humanity encountered mass electrification, telephones, automobiles, radio, movies, airplanes, submarines, elevators, refrigeration, public education, radioactivity, feminism, Darwin, Marx (who wrote, “All that is solid melts into air”), Picasso and Freud. It is particularly ironic that just as modern people were learning of the unconscious, they found themselves forced to act out the old myths of the sacrifice of the children.

Now everyone was judged by how useful they were under capitalism. In 1900 George Simmel wrote that existence in the urban factories had diminished human passions in favor of a reserved, cynical attitude. This had created a compensatory craving for excitement and sensation, which for some was partially satisfied by the emerging consumer culture. But others needed something even more extreme, more Dionysian, to make them feel alive. The mass euphoria of belligerent nationalism provided it.

Ouranos had been in the ascendant. But he soon evoked his opposite. As a group, the generation of older men of 1914 were embodying Kronos, the god who ate his own children. The pace of technological change simply exceeded humanity’s capacity to understand it, and the pressure upon the soul of the world exploded into world war.

How did this play out on the battlefield? Any honest military historian will admit that the generals (or in this context, the ritual elders) learned absolutely nothing in those four years. They began in August 1914 by exhorting the troops with Dulce et Decorum est Pro Patria Mori and then sending wave after wave of boys just out of high school against massed, fortified machine guns. A million died in just the first four months. Yet four years later, in late 1918, tactics hadn’t changed at all. The poet Wilfred Owen (who would die in the last week of the war in yet another senseless and suicidal assault) described the terrible irony of the soldiers’ experience:

Dulce et Decorum est

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame, all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin,

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues –

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

These are profound mysteries. Perhaps the old men did learn some things, even if none would dare articulate them: that myth trumps fact; that they remained free to enact these horrific narratives; that far from being punished, the worst of the warmongers would go on to live with the highest honors and privileges – and that the story would go on unchanged.

On November eleventh, 1943, the Nazi S.S. memorialized the 25th anniversary of the armistice with a display – uncommon even for them – of gratuitous cruelty. They forced the 40,000 residents of the Terezin ghetto in Czechoslovakia to stand at attention in a freezing, rainy field all day for a head count that didn’t happen until late afternoon. Anyone who moved was shot. Three hundred collapsed and died before they were allowed to return to their barracks.

It had to end in 1945, we’d like to think.

Certainly, twenty years after the end of the Second World War, after Korea, the generals had finally learned that it was useless to send infantry against machine guns, right? Wrong. Throughout the Viet Nam war, the U.S. Army’s primary tactic – “search and destroy”, or “target acquisition” – was the sacrifice of infantry units to flush out the concealed enemy. Helicopters intentionally dropped troops into “hot zones,” where they were often pinned down by enemy fire. They defended themselves until air strikes hit the enemy positions, and then the American survivors left the terrain to the enemy’s survivors. No actual ground was liberated or acquired, and few precautions were taken. Sociologist William Gibson writes,

Story after story…concerns commanders who knew large enemy formations were in a given area but did not tell their subordinates because they did not want them to be cautious.

In countless other examples, the Army expended American lives to force the North Vietnamese off steep mountains for no discernable purpose. The 1987 movie Hamburger Hill depicts the nine-day assault on “Hill 937”, designated as such because it’s height was 937 meters, and costing 72 American lives and hundreds of wounded. The film ends with a victory celebration. What it doesn’t show, however, is that most of the North Vietnamese escaped and that the Americans abandoned the hill two weeks later.

Abandonment and betrayal (mythologically, Ouranos and Kronos) became the primary metaphors understood by hundreds of thousands of Americans, even if they’d never heard a Greek myth. Psychologist Jonathan Shay writes that the soldier’s common experience was violation of the moral order, or betrayal. He quotes one veteran: “The U.S. Army…was like a mother who sold out her kids to be raped by (their) father…”

In the decades after the end of that war, American elites, with the assistance of Hollywood filmmakers, made a determined effort to rehabilitate its criminal memory as (at worst) an honorable crusade and (at best) a tragic “mistake”. In the public mind the veteran was now either a violent thug or a victim – not of a culture that ate its children, but of liberal politicians and cruel Vietnamese torturers directed by scheming Russian overlords.

I invite you to consider, however, whether the war was really a mistake. Cui Bono, follow the money. Great fortunes were made, as they would be made during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and as they are being made right now while the U.S. intervenes in Ukraine, Yemen and Ethiopia and funnels billions to the arms industry.

Perhaps more importantly, the mythic fix is in as well, in the shape of the “good war”. The public remembers Viet Nam as a tragic mistake conducted by men who had the very best of intentions. It remembers Iraq and Afghanistan in precisely the same mythic terms. It will remember Ukraine in the same way. The myth of American innocence is being reconstituted and revived for yet another generation of old men who are already anticipating the next opportunity to feed more young men into Kronos’ gaping maw.

All this leads me to suggest that when you consider speaking to a veteran today, think before you do. What precisely will be your intention? Will it be, as veteran James Kelly writes, “…an empty platitude, something you just say because it is politically correct”? Will it “…massage away some of the guilt at not participating themselves”? Will it be “…almost the equivalent of ‘I haven’t thought about any of this’”? Kelly also writes:

After all, despite the various reasons that people join the military, from free college to a steady paycheck to something much more patriotic or idealistic, there is one thing we all have in common: Our passion for our country and your rights and freedoms that we swore to protect.

May it be so, and may passion for country grow into passion for the Earth.

Full disclosure: I acknowledge that I am not a veteran, and I have no concrete, felt understanding of a veteran’s experience, let alone the experience of combat, wounding or trauma, or even of their family’s pain. But I must tread – lightly but firmly – into this “morass” (to coin a phrase). I sincerely hope that Mr. Kelly would support this statement: We fought to defend your free-speech right to completely disagree with our reasons for fighting.

Myth and politics (radical politics) can meet. Howard Zinn, who became a pacifist after serving as a bombardier in World War Two, put Veterans Day in what I consider to be its proper perspective:

Our decent impulse, to recognize the ordeal of our veterans, has been used to obscure the fact that they died, they were crippled, for no good cause other than the power and profit of a few. Veterans Day, instead of an occasion for denouncing war, has become an occasion for bringing out the flags, the uniforms, the martial music, the patriotic speeches reeking with hypocrisy. Those who name holidays, playing on our genuine feeling for veterans, have turned a day that celebrated the end of a horror into a day to honor militarism. As a combat veteran myself, of a “good war,” against fascism, I do not want the recognition of my service to be used as a glorification of war. At the end of that war, in which 50 million died, the people of the world should have shouted “Enough!” We should have decided that from that moment on, we would renounce war… war in our time – whatever “humanitarian” motives are claimed by our political leaders – is always a war against children…Veterans Day should be an occasion for a national vow: No more war victims on the other side; no more war veterans on our side.

How often does the statement “Thank you for your service” serve as a personal apology for the knowledge of how shameful the nation’s actual treatment of vets has been? No one really knows how many veterans have (or had) “passion for their country,” or how many believe that it is a sweet and noble thing to die for it. But the mythmakers and gatekeepers are going to extraordinary lengths to convince you that they do, and to marginalize anyone in media who disagrees. Caitlin Johnstone writes:

Don’t say “Thank you for your service” to veterans. Don’t pretend to agree with them when they claim to have fought for your freedom and democracy. Openly disagree with people who promulgate this narrative. Treat Veterans Day and Memorial Day as days of grieving and truth-telling, not celebration and glorification…“But Caitlin!” you may say. “What about World War Two veterans?” Well, fine, but…do you notice how far back you had to reach in U.S. history to find a war in which veterans arguably fought for a just cause?…There are no war heroes. There are only war victims.

To counter the onslaught of what really is fake news, imagining a new way of being requires a reframing of “the old lie”. One step would be to rename Veterans Day as Armistice Day and celebrate its original meaning. As Chelsea Manning tweeted,

Want to support veterans!? Stop sending us overseas to kill or be killed for your nationalist fairy tales. We can do better.

If America were to miraculously awake from its 400-year dream of innocence and denial and speak honestly for once, we might admit that Veteran’s Day is really Sacrifice of the Children Day. Here’s an alternative to “Thank you for your service”: I can never know what you went through, but if you’re willing to speak about it, I’m willing to listen. And if possible, I’m willing to share your grief.

Yes, praise the vet, not the war. Praise real elders like Howard Zinn, not the con men who avoid military service and feed a bloated defense budget. Praise grief processions, not parades of military hardware. Praise a veteran’s willingness to help us change, not romanticization of his battles. Praise the desire for initiation, not the sacrifice of the children. Praise commonalities, not otherness.

My name is Francis Tolliver. In Liverpool I dwell

Each Christmas come since World War One I’ve learned it’s lessons well

That the ones who call the shots won’t be among the dead and lame

And on each end of the rifle we’re the same

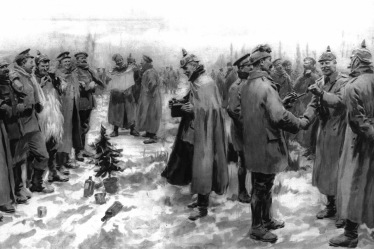

– John McCutcheon, “Christmas in the Trenches”

Some related essays of mine: