“It is clear that our old stories aren’t doing the job of instilling sustainable values and congruent practices, and that we need a new mythology that is responsive to the needs of our planetary emergency. Our new narratives need to be at once more truthful and empowering, inspiring a level of social change thus far unachieved by our era of access to information. With the application of carefully constructed cultural memes, crafted with responsibility and integrity, it may be possible to reach far more people with the internalized values and constructs of a sustainable paradigm. We need to replace the myth of humanity holding dominion over nature with the truth that we are simply a part of nature’s complex web of symbiosis.” KM

* * * * * * *

Interview with Kari by Willi (her article follows):

Who are the storytellers of the Permaculture Age?

Good question. I may interpret this one a little differently than intended, so please feel free to re-direct me if I go off on a tangent!

For me the storytellers of the Permaculture Age are those who are weaving the socio- cultural narrative of the Permaculture era. These can be any people who choose to tell that particular story through their actions and interactions. Aside from the obvious Permaculture heroes of Bill Mollison and David Holmgren there are others who have had a profound influence due to their own interactions with the Permaculture narrative. Such proponents of a sustainable new paradigm include Richard Heinberg and the Post-Carbon Institute, or Rob Hopkins and the Transition Towns Movement. Having mentioned these heroes I think it’s important to give some attention to the everyday heroes whose names we never hear of and are never likely to. Positive change wouldn’t be possible if it weren’t for the everyday heroes who participate in such movements and initiatives – the guru alone cannot create change; they can only command and inspire it. The rest of the chapters of the story need to be told by the active participants, as we are necessarily active participants in change, not mere recipients. Those who realize this become the storytellers, and the more conscious they are of this role the more effectively they fulfill it.

Do you see yourself as a writer of new myths or a critic of these attempts? Both?

I definitely see myself predominantly as a writer of new myths. That is not to say that I don’t see the value in critiquing the attempts of others – whether positively or negatively – and I tend to only offer supportive, positive critique as I see that as a more productive use of my time regarding generating positive change. I certainly enjoy researching past attempts and extrapolating from previous efforts at new mythology creation in order to build upon them and infer likelihoods for future successes.

However, as a creative I prefer to actively participate in the construction of new narratives, new mythology. My first love was writing and I have always been fascinated by stories – particularly the real-life stories of everyday heroes and historical events. Through history and biography one can learn much of what has worked and what hasn’t worked regarding social and cultural change; and it is clear that what has been most successful in generating change – be it positive or negative – is storytelling, the narrative that gets under the skin of society and creates gentle paradigm shift whilst the populace are to a large extent unawares (besides the obvious pioneering types). If I am able to effect the most subtle of changes via the writing of new myths then I will have achieved what I consider to be wonderful things, most unbeknownst to those who will re-tell the stories and generate changes through their own lives and actions.

Can you tell us who your new myth heroes are and why?

My new myth heroes are those who I see exemplifying the everyday person rising to the challenges we see before us. My heroes include people such as Helena Norberg Hodge of ISEC and Economics of Happiness, as she has told an alternative story about what constitutes real wealth – something that we cannot have if we only ever pursue monetary wealth. Vandana Shiva is another hero for me as she has been a huge inspiration in the grass-roots people’s movement for food sovereignty, arguably the most fundamental asset for a liberated and sustainable society. I also see Derrick Jensen as a hero for his courage in telling truths that must be told regarding our level of avoidable damage to our planet, and his explanations of all social norms as narratives that can, and should be – in many cases – re-written.

My favourite myth hero, though, it has to be said, isn’t a new myth hero, but an old one. For me the myth of Cassandra has always held an almost romantic, yet tragic fascination and it resonates greatly with me for what I consider to be my “Cassandra Complex”. Cassandra was not a hero in old mythology as he prophesies were ignored and ridiculed, doomed as she was to envision the truth of what would come yet be believed by no one. I’m sure many heroes of our new mythology era would sympathize with this plight, and it is one that has plagued me throughout my adult life. I hope to re-write the narrative of Cassandra in a way that alerts people to the need to consider even that which they may not yet see as credible due to their own deficit in understanding.

Isn’t storytelling “hopelessly” old fashioned and un-mediated? How do you measure the success of this activity?

Perhaps it is old-fashioned, but certainly not “hopelessly” so! Storytelling is a practice that humans have used for millennia to communicate information and practices conducive to our survival, and we will continue to use it for millennia to come if we survive to do so. I feel that storytelling has been somewhat neglected in our information era as or culture, at least Western culture, now places a lot more faith in cold, hard scientific facts, much like the enlightenment era. Although these cold, hard, scientific facts are absolutely vital to our understanding of the world around us they generally do not resonate with many people, do not inspire behavioral change, are perhaps not sufficiently tangible to do so. Therefore I favor more the use of such information to underpin stories, much as the romantic poets of 18th Century Britain did as their response to the shortcomings of the Enlightenment era. I feel that we are now, in our rapidly developing hi-tech era, going through another Enlightenment spiral in which we need the balance of storytelling to deliver information in ways that can inspire positive behavior-change.

Ultimately storytelling is an unmediated practice and its success at present is immeasurable, at least by any practices I know of. Again, it might be a little hangover from new Enlightenment values to feel a need to measure everything in order to point to direct causative effects. I certainly feel this need myself, but am aware that interactions are far too complex and often too subtle to see with the naked eye, so to speak. History does a wonderful job of tracking change in a way that can assist us in making inferences regarding what may or may not have been effective. So, although our measuring tools are blunt the success of storytelling can be inferred as certainly greater than the delivery of cold, hard facts if we look at examples of behavior change throughout history.

Do you agree that the classic myths are no longer in play in our lives? Please explain.

No, not at all. I see the classic myths as having a profound impact on our modern lives. As I mentioned before, for me the myth of Cassandra is the myth of our present era as we are facing a planetary crisis of the magnitude never seen before in human history and we are ignoring, ridiculing and disbelieving the wisdom of our prophets. From such myths we must take heed and work to ensure we treat them as a warning. In addition, many other classic myths are recycled and used in modern-day storytelling as they have been throughout millennia. The use of certain hero figures has always been effective, and despite cultural changes it is not difficult to update classic myths and heroes to new contexts and settings. If you think about it, we’ve been fed with the inspiration of classic myths to the extent that all of our modern storytelling is done from the elevated position we only have when standing on the shoulders of giants. The classics will not become irrelevant, just updated to keep pace with our ever-changing world.

by Kari McGregor, Editor, Spirit of the Times

Issue 8, 11/12

In a culture of storytelling mythology is the cornerstone. It informs and shapes our worldviews with the power to construct, change, or challenge our view of reality, gently directing the course of our civilization’s development.

Humans have evolved a culture of story-telling as a way to pass information from one person to another, from one generation to another, a way of contributing to a common repository of information by which we are able to learn and develop. In this way we are a unique species – our adaptability to our environment enhanced by our ability to consciously store, transmit, and accumulate pools of knowledge.

This story-telling has enabled us to make huge advances in our social, political, economic and technological innovations, exponentially increasing the shared knowledge repository of humankind. Stories enable us to instill cultural values – most traditionally connected to our needs and that of our land base – and ensure that they are internalized from the very young to the wise elder. Telling stories is the way in which we ensure that certain behaviors are characterized as good, or heroic, while other behaviors are immediately seen as bad, or villainous – a simple way to elicit desired behaviors from our kids, our employees, our populace.

But the telling of stories is a double-edged sword. Those who craft and perpetuate the stories of our culture are in a position of both great responsibility and great power – the power to influence, even determine, the behavior of whole populations. This power is not always used for good, and the responsibility often evaded – as is the case with mass-media distributed propaganda. Examples such as the work of Ayn Rand – who crafted a suite of heroes whose job it was to rationalize the concept of self-interest as the greatest of all virtues – demonstrate how even popular fiction can be used to generate a cultural meme of profound effect, with Alan Greenspan, economist and former chairman of the US Federal Reserve, listed as one of Rand’s closest followers and a key player in the sub-prime mortgage crisis that led to the Global Financial Crisis.

Recognition of internalized concepts as stories enables us to alter our detrimental and unsustainable worldviews in favor of views that are more in line with natural world realities, and thus more amenable to our sustainability. We are, it seems, both the master and the servant of our mythology, our servitude all the greater if our mastery is the lesser.

Our culture’s embedded Mythology

Some of the myths of our culture are so deeply ingrained that we fail to recognize them as stories, instead assuming that our limited and filtered worldviews are simply rational and objective assessments of our reality.

At the root of our erroneous worldviews – the views that are fast-tracking us towards annihilation as a species – is the notion that humanity has dominion over nature. The origin of this concept long predates the biblical references to it, yet it is, nevertheless, a religious belief – one that has become so entrenched that even atheists who have long since cast off the mantle of religion subscribe to and repeat it as though it were absolute truth. The false and arrogant belief in our dominion over the natural world has led us down the path of destruction only an Old Testament God could incur. We fear wild nature and seek to tame it, fencing ourselves into concrete enclaves within which we foster the belief that all else is beneath us. We distrust the wisdom of Mother Nature, insisting that our own technological offerings are superior to her craft. We use the offerings of the natural world for our own selfish gain, failing to recognize the needs of other species as equal to our own – for they, too, are under our dominion. We punish the natural world for its inferiority to our perceived greatness – we tear up forests, vacuum oceans, blast the tops off mountains, create vast swathes of desert, bleed our rivers dry, and we enslave, torture, and murder animals in a daily holocaust of biblical proportions. Yet the reality is that we have no such dominion. We have the power to influence our environment, as evidenced by anthropogenic climate change, but not to control it, as is abundantly clear from our humble submission to nature’s most awe-inspiring feats of destruction.

From the story of our dominion over nature stems our concept of ownership. If we are able to dominate the natural world we are then able to own portions of it, buy and sell those portions, and generate further wealth from the production of goods from its looted resources. We tell ourselves the story that we are entitled to own regions of nature’s kingdom and we compete for this perceived entitlement, destroying the very amphitheatre in which we stage our battles. The competition for ownership unleashes the atrocities of war, slavery and imperialist conquest, with the fallacy of entitlement the very concept with which our culture of empire justified the decimation of 99.6% of the American Indian population. Our sense of entitlement to own knows no bounds – the enslavement of our less entitled brothers and sisters worldwide is what facilitates our insatiable hoarding of iCrap; the rape and pillage of our life-giving biosphere is what affords us our glitzy shopping malls and highways between havens; through grabs for land and water the starvation of our fellow humans is what enables us to self-pityingly experience obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease – the maladies of our own affluence. Yet the truth is that we in the west are simply able to pay for all this. We know better the rules of the game and are born on the winning team. The reality is that we never truly own anything. Once the game is over everything goes back into the box. We can’t take it with us.

Further disrupting the harmony of what could be, we demand our economies grow because such growth is both desirable and necessary – another myth generated from our sense of dominion over nature and the concept of ownership. We believe that economic growth is desirable as it will enable us to have more of the finer things in life – things our ancestors could not have imagined possible, such as fast cars, jet planes, swimming pools, designer clothes and holidays in exotic locations; we view it as necessary because it enables an acceptable standard of living for all with access to food, water, shelter, energy, healthcare and education. Far from giving the poor a leg up to attain levels of material security and genuine opportunities, economic growth simply funnels wealth to the owners of capital, making a mockery of the trickle-down fallacy while accelerating the rate of material throughput and the depletion of the fossil fuel and mineral resources that make our short-sighted dreams come true. The reality is that economic growth is only necessary for one thing – the perpetual growth of the Ponzi scheme that is money in order to provide greater wealth to the already obscenely wealthy. In our insatiable quest for wealth our worldviews have become dangerously decoupled from what we really need for survival – and none of the needs on Maslow’s hierarchy pertain to luxuries of the material world that only serve to undermine our access to safety, security, meaningful relationships, and the spiritual goal of self-actualization.

The Protestant work ethic is a narrative that has propelled our society in its quest for economic growth and prosperity, and control over nature via sheer hard work. We believe that our desires only remain out of reach due to insufficient effort on our part, and that those who have what we desire have earned it through the sweat of their labor. Those who toil under slave-like conditions in mines for the production of the rare minerals from which our well-deserved iCrap is made must simply not be working quite hard enough as they lack the money to send their children to school, much less ever own an iPhone. Those who labor most hours of the clock to produce the designer finery in which we sip cocktails and self-aggrandize our own accomplishments must simply not be putting in quite enough time as they merely subsist on the meager rice their time buys, never dreaming of donning the garments they produce in abundance. Even we, the worlds wealthy, are never working quite hard enough to fuel the economic growth machine and fully realize our dominion over the earth. What needs to be challenged in this narrative is not work, but the material success-oriented ethos, the climbing of the ladder to power, and the resultant status that awards the winners of the game the moral right to a piece of the feudal kingdom. The reality that needs to be told is that hard work by itself – i.e. without the propellant of privilege – is rewarded, in most cases worldwide, by exhaustion, and not the promised livable wage, much less the American Dream.

A culture of denial

Dancing hand in hand with our culture of mythology is our culture of denial. With the elaborate falsehoods we have woven come the need for ever more elaborate justifications. Justifications for our actions and worldviews involve further layers of narrative such as “human nature is inherently greedy, selfish and competitive”, or “this is the way it has always been”, or “nature would have made things different if it were not supposed to be this way”. When confronted with reality we deny that our worldviews are faulty, insisting that any challenge to our most sacred of beliefs must simply be wrong. Our confirmation bias serves the 40 November 2012 / Spirit of the Times Magazine maintenance of the status quo, and our trajectory toward collapse of our beloved way of life.

A move toward adopting a new mythology, a more honest set of narratives for a worldview in sync with reality is one that will not come easily. In our denial of any alternative views and ways of life we are trapped in a cycle of Cassandra-like despair, in which the wise fervently preach portent of what is to come if we do not mend our ways, and we ignore the ill-fated messengers who fail to dislodge our minds from their comfort-zone of embedded myth.

Historical precedents

We face a gargantuan task in bringing a more realistic narrative to a society founded upon a denial of reality. However, this task has been attempted before throughout the ages, and with incremental successes via media of various forms from Plato’s The Republic to Thomas Moore’s Utopia to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Certain points in our history have sparked entire movements of trajectory-changing narrative, injecting truth into public consciousness, and the hope that another way is possible.

The First World War brought forth a wave of literature telling of truths obscured by the mainstream media mythology of the day. While the newspapers were pressing young men to enlist in the army to “fight for their country” poetry was flooding back home from the battlefield telling truths of what was. Wilfred Owen’s Dulce Et Decorum Est provides a bitter and vivid account of life in the trenches in the age of chemical warfare as well as an enduring critique of the popular myth – a brazenly alternative narrative to that of the ruling class. The final four lines hold a raw and bitter beauty of a truth dared told:

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori

Attempts to positively influence the course of social development through narrative surged during the era of Romanticism, beginning in the mid-late 18th century in the UK – while the founding fathers were theorizing economic thought. This movement was a philosophical, political, literary, cultural, and artistic challenge to the Enlightenment movement, which was of a more intellectual bent with the purpose of reforming society through the use of reason and advance knowledge through science. The Romantics were of the view that society could not be reformed simply by the application of information and reason, but that a narrative would have to be woven – a view in line with our emergent contemporary understanding that informing society of ever more facts and figures does not have the desired effect for social change.

Fundamental to the Romantic movement was the belief in the natural goodness of human nature. It was theorized that, contrary to popular contemporary and historical belief, in a “state of nature”, humans would do good, not harm, but that civilization as we had created it provided a hindrance to our natural expression, with William Blake claiming that: “urban life and the commitment to “getting and spending,” generates a fear and distrust of the world.” The Romantics also expressed commitment to change – a dynamic rather than static way of being, spinning a narrative of a perfectible humanity, that moral as well as technical progress is possible. The Romantics’ greatest enemies were cast as the successful bourgeois, or the Philistine with a vested interest in maintaining the status quo.

Romantic poets stressed a love of nature in their work – the controversial literature of their day – with Samuel Taylor Coleridge referring to poetry as a “… media tress between, and reconciler of nature and man”. Nature was referred to as an exemplar and source of physical beauty, as well as embodying a more metaphysical manifestation of spirit in the universe.

It was believed that the structure of society and politics had led to a culture of servitude and oppression, and that a departure from materialism and possessive ownership in favor of values more congruent with the needs of the natural world would assist in catalyzing a much-needed fresh start. Such views were heavily influenced by accounts of “new world” travelers who had had contact with First Nations’ peoples.

From the era of Romanticism emerged Coleridge and Robert Southey’s “Pantisocracy” – plans for an egalitarian community of people living a more simple life in accordance with the dictates of Mother Nature and with common ownership of all land and resources. It was believed that the creation of such an exemplar community would cement a positive narrative in people’s minds that such a way of life was not utopian, but real and possible. However, the Pantisocracy society never came to pass due to disagreements arising between its would-be founders regarding the integrity of the scheme.

It seems our society may be yearning for a new wave of Romanticism to communicate the messages that our modern-day Enlightenment of the purely intellectual is unable to convey, and to reach people in the ways that cold hard facts and figures cannot. New stories will be needed.

Telling a new set of stories

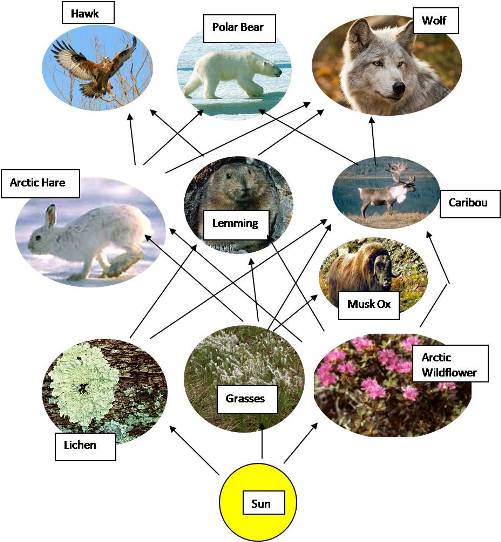

It is clear that our old stories aren’t doing the job of instilling sustainable values and congruent practices, and that we need a new mythology that is responsive to the needs of our planetary emergency. Our new narratives need to be at once more truthful and empowering, inspiring a level of social change thus far unachieved by our era of access to information. With the application of carefully constructed cultural memes, crafted with responsibility and integrity, it may be possible to reach far more people with the internalized values and constructs of a sustainable paradigm. We need to replace the myth of humanity holding dominion over nature with the truth that we are simply a part of nature’s complex web of symbiosis. An understanding of our place in the ecosystem can be facilitated by simple stories embedded in our culture from early childhood, and serve to inform our responsible custodianship of our land base.

The narrative of entitlement to ownership needs to be replaced with that of common access to all that nature provides. A new mythology needs to bear forth the truth that equity is a moral and practical imperative in any healthy and functioning society, leading to something much more akin to the African concept of Ubuntu, in which it is said that “I am because we are”.

Our doctrine of perpetual growth needs to be cast aside now that we understand the growth paradigm is faltering. A steady-state economy is one which needs to be embraced by positive narratives telling of the quality of life that can be experienced in a world post-growth, a world in which people labor fewer hours and have more quality time with loved ones, a world in which our obsession with material possessions is replaced with an embracing of rich life experience. Hand in hand with the notion of a steady-state economy comes the replacement of the work ethic myth with stories of the wondrous creativity of the human spirit in a life unrestrained by the shackles of monetary-motivated labor.

And in order to truly empower people to be the change they wish to see we need to break free of the myth of human nature as self-serving narcissists. With a new narrative informed by the findings of contemporary psychology people may seek to express the best of human nature and become the heroes of their own new mythology.

Cultivating a new heroism

The challenge now before us is to craft a new mythology in which our heroes are ordinary people like ourselves who pave the way toward a sustainable future. Instead of the high positions held by our heroes and gurus of old we must remove the pedestal and create a construct of heroism to which all can aspire and reach. Unlike Ayn Rand’s self-serving heroes who benefit in parallel with the losses they inflict upon others our new narratives may feature heroes celebrated for their empathy, altruism and collaboration with their community, with our new villains being those who undermine sustainability in their failure to be mindful of the consequences of their actions. Our heroes need to reflect the journey we, ourselves, must take in becoming and creating the change we wish to see.

Whatever the form of our new heroes or the journeys they will take we must pay attention to the responsibility that we all hold – our responsibility to tell our new stories, to add to the pool of knowledge, to pave a sustainable direction for our children’s future. It is we who are to be the heroic authors and narrators of our new mythology, a mythology which, when itself grown old, will be famed for its dramatic rescue of humanity from the cliff-edge on which we now stand.

Replies