PART FOUR – THE PARADOX OF THE OUTSIDER

The redemption hero, like the Christ, always comes from outside the community. And like the Christ, he leaves once his work is done. He must leave; redemption mythology requires that since he came from somewhere else, he must return. But this leads to a paradox. The innocent community defines itself by what it is not – the external Other of terrorism, and the internal Other of race. We know who we are because we are not them, the others. The Other is the evil, threatening outsider. Or: evil (that which is not-Eden) comes from the outside – but so does redemption.

By riding off into the sunset, writes James Robertson, “…the cowboy hero never integrated himself with his society.” This hero has much in common with his villainous antagonists. Each rejects social comforts and conventional rules of law to further his aims or serve his cause.

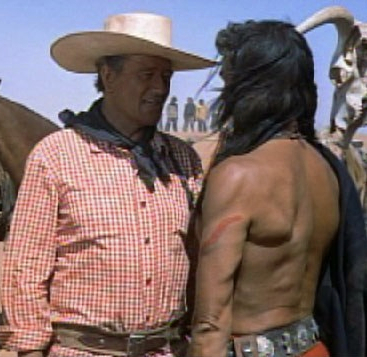

As I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, the birth of the national security state coincided precisely with the peak of the Western in film and TV. Our classic example of the outsider hero who leaves once his work is done is Shane, which was produced in the same year (1953) that the CIA overthrew Iran’s democratic government. And our classic examples of the unity of hero and villain

are John Wayne’s character “Ethan Edwards” and his enemy “Scar” in The Searchers (1956). Although Edwards and Scar serve opposite ends of the moral spectrum, their methods are surprisingly similar.

Here is the final scene of Shane:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtoCw2iOTSc

Ultimately, a characteristic of the American hero is his willingness to become an outlaw in order to defeat evil. Richard Slotkin, in Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600 -1860 writes that as early as the 1820’s the standard, fictional frontier hero was rescuing white captives by fighting the Indian “on his own terms and in his own manner, becoming in the process a reflection or a double of his dark opponent.

To this day the public often admires the outlaw nearly as much as the lawman (queue Trump again). Jesse James pulled off an 1872 bank hold-up so skillfully that the local newspaper described the exploit as “…so diabolically daring and so utterly in contempt of fear that we are bound to admire it and revere its perpetrators.” Perhaps more so: Al Capone received standing ovations when he appeared at ball games, and gangsters from the fictional Tony Soprano to the actual John Gotti (who had his own TV show) were idolized in the press. For more on this, An Offer We Can’t Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of America, by George De Stefano.

Robert Warshow writes that the gangster is “what we want to be and what we are afraid we may become.” Both share still another characteristic: the villain’s rage is a natural component of his pleasure in violating all boundaries, while the hero is also full of rage. Only by killing the villain, writes William Gibson, can he “release the rage accumulated from a life of emotional self-denial.”

The Puritan zeal for order always clashes with our equally mythic desire to accumulate wealth through any means necessary, and the American psyche has long had to hold both of these themes together in a very unstable mixture. Thus, writes Joel Kovel, “The law enforcer and the law-breaker express contradictory impulses which have been joined in the American character.”

Lewis Lapham suspected that G. W. Bush (and, I would add, Trump) owed his popularity to our inclination to romanticize criminals:

Whether cast as the hero or the villain of the tale, the man at ease with violence bends the rules to fit the circumstance…Bush (feels) entitled to his cocksure swagger by virtue of his having stolen his election to the presidency. The robbery…admits (him) to the long line of America’s criminal ancestry.

Though the hero chooses a life outside of society, he is hardly alone; the desperado and the corporate raider whom we can’t resist admiring are out there too. And, curiously, they are joined by all of the assorted Others – Indians, blacks, Asians, Latinos, youth, gays, Vietnam veterans, terrorists, the disabled and the homeless – those who have been exiled, pushed beyond the walls or into the underworld, into the territory of the repressed. Indeed, the term “underworld” was first used to describe organized crime in the 1920’s, just as the movies were establishing themselves as the prime purveyors of American culture, and alcohol (liquid Dionysus) was being banned.

But America’s re-telling of Biblical redemption stops short of the profound truth conveyed in Euripides’ The Bacchae: the “evil other” and the redeemer, the “good other,” are one and the same, existing together in the mythic figure of Dionysus. In the original Greek, Xenos (root of xenophobia) means both “stranger” and “guest,” depending on the context.

Such a polytheistic culture could hold the tension of these opposites, but monotheism cannot. Christianity had to split Dionysus into two antagonistic images, Christ (himself both mortal and immortal) and the Devil. American myth turned them into the hero and the villain, and American capitalism turned them into the winner and the loser.

From the perspective of authentic initiation, we can see the destructive element that religious, economic or political fundamentalists perceive as evil is actually the revival of long-repressed energies, arriving now as the symbolic death, the redemption, necessary for rebirth to occur. Older figures like Dionysus and Osiris died and were reborn repeatedly, personifying the masculine aspect of the changing, natural, organic world. They were the original dying gods who preceded Jesus. For much more on this theme, see The Jesus Mysteries, by Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy.

But in monotheism, the savior dies only once, not as the world but as a sacrifice for the world. In the context of patriarchy the redemption of the fallen world requires no death into greater life, but only the sacrifice of a child for the benefit of the father. Or: the child’s death equals the redemption of the father’s world.

The empty tomb implies that Christ has returned to the ultimate abstraction, pure spirit. He refuses (or his father won’t allow him) to stay in the ground, in relation to mater, matter, the mother, relationship, Earth.

Certainly, the tradition of tragic literature has offered us some protagonists, such as Hamlet, who actually die. Such heroes typically gain some self-knowledge, so their deaths can have symbolic and initiatory meaning.

But that tradition has its roots in a pre-Christian world, unlike the American hero, who emerged out of monotheism. This hero is willing to die in order to save the innocent community, but he rarely does. John Wayne’s characters, for example, die in seven of his 156 films, usually after having saved his comrades from danger. Are these deaths conceived as sacrifices, and to what? Or are they simply a return to the spirit world, the realm of the distant father gods?

Much more often, after restoring innocence to Eden, the Western Hero rides off into the sunset, leaving the feminine community. Either way, he chooses union with the father over the anxiety or tedium of life among the women and children. Or: dying to the world and attempting to unite with his distant father, he becomes an alcoholic, chasing after “spirits.” He may leave by conscious choice (in much tribal lore the sunset in the west is the land of the dead), or by his father’s choice (“fate”). No wonder that American funerals are so unemotional. Why cry for someone who has gone to a “better place” than this one?

Unlike the universal hero who lifts the veil between the worlds to bring awareness of eternal values to humanity, the redemption hero pulls the veil back down, confirms our innocence, and puts everyone back to sleep.

In literal terms, the real danger is that he may well be forcing us all (think North Korea and nuclear weapons) to join him in returning to that “better place” of pure abstraction and pure oblivion.

But we must always remember that both traditional hero myths and traditional initiation rituals require that something must be sacrificed – the interior identity of the adolescent macho hero – in the course of the hero’s journey. Even though he must leave it for a while, he is bound both to his community and to the Earth, the actual place of that community.

Redemption mythology does get one thing right: the hero must die before he can become the archetypal warrior, who is native to, lover of and defender of the realm. But without the return to that realm, to community, to relationship with the feminine, his initiation remains incomplete, and his tendency toward heroic action – whether literal or vicarious – becomes addictive, and thus repetitive. Such heroes (and their vicarious admirers) long to die into something greater, so they compulsively challenge the world to give them that literal death, in Bush’s words, to “bring it on.”

The tragic tradition says: the hero must die so that he can grow into deeper knowledge. Tribal initiation says: the boy/hero must die so that a real man may return to his community. Psychology says: the hero must die so that the child in the background may finally be put to rest and space can be made for the archetypal Warrior to emerge. Religion says that the Redemption hero must die so that so that the world can have a new imagination of heroes who live for the world instead of heroes who die for it. History says that the idea of the American hero must die so that women and oppressed peoples everywhere can have their full rights in the human community.

The final chapter of my book includes these words:

Heroes certainly won’t disappear; the earth needs real heroes like never before, but we will prefer “peace heroes” to “war heroes.” As we support ritual containers for initiation…we will feel the hero’s journey within ourselves. We will no longer be fascinated by men who risk their lives crushing the Other to restore the peace of denial. We will applaud those who commit to the hard work of relationship with the feminine, men who don’t ride off into the sunset…Rebirth will hinge upon replacing Rambo with Odysseus, who leaves home a hero but returns transformed by his initiations at the feet (and in the beds) of goddesses. Having encountered many small deaths, he returns as the saved rather than the savior. As they say in Africa, when the big death finds him, it will find him alive.

May this nation learn, before it is too late, to see this challenge in symbolic terms and to awaken from this dream of separation.