Part One

What is madness but nobility of soul at odds with circumstance? – Theodore Roethke

Divide us those in darkness from those who walk in light. – Kurt Weill

Dionysus was the ancient Greek god of wine, drunkenness, masks, frenzy, ecstatic joy, paradox, suffering, tragedy – and madness. Wherever he appeared, he subverted the classical Greek consensus of reason, exalted discourse, and refined culture. He posed annoying questions upon king and philosopher alike, tore down the walls of the isolated ego and insisted that everyone was fundamentally animal, social, instinctual, sexual and irrational.

In terms of Depth Psychology, he represents the paradoxical archetype of the Other. He is an aspect of nature – and human nature – that is both outside the boundaries of the known, familiar and acceptable, but also deep within, at its very core. Since he confronts us with the mystery behind the reconciliation of opposites – male/female, active/passive, light/dark, mortal/immortal, sacred/profane – we can only define him by what he isn’t. Simply by showing up at the gates of the city (or the mind), he threatens our carefully built sense of who we are. He reminds us that identity is constantly shifting.

Consequently, patriarchs and authoritarians have attempted to repress the Dionysian impulse for well over two millennia. However, his modern incarnations persist in our imagination as the Other. He is everything that America has cast into the shadows: women, gays, non-bindery or transgender people, people of color and poor people. But this happens at a great cost. By denying this innate archetype, we deny much of who we are, because, as Walt Whitman taught us, we all contain multitudes.

If Dionysus were to speak to Psychology and the medical establishment in the Age of Covid, economic instability, Black Lives Matter, climate change and a collapsing American empire, he might ask certain annoying questions, such as:

Is a child molester a criminal, a sinner or a sick person? Why do we think of a terrorist or a tyrant as evil rather than sick? Why are convicted murderers not considered insane? Why do we punish criminals instead of rehabilitating them? Why does America demonize its children simply because their parents are poor? Why are we so violent? Why are the mentally ill disproportionately female and poor? In a dysfunctional culture, what is a dysfunctional family? What is functional? Why do we take so many drugs, legal or otherwise? Why, in these maddening times, isn’t everyone running through the streets raving and grieving? Isn’t willful innocence a form of madness?

Perhaps all these questions can be rolled into this one: Why are Americans so Freaking Crazy?

Invoking this god as my guide, I want to circle around these themes in a Hermetic, Dionysian, soulful, non-linear manner, showing more interest in surprising connections and brief liftings of the veil than in logical proof. In his realm, the questions are more interesting than the answers.

The god of madness lives in our asylums and halfway houses and among the homeless. And at home: In any given year one in four adult Americans suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder. Six percent are seriously debilitated; and half will develop a mental disorder at some time in our lives. Depression has doubled since World War II, with each generation showing increasing rates. It now impacts twenty million American adults. One in ten women and six percent of children take antidepressants.

Nearly half of young people have been diagnosed with some sort of psychiatric condition (counting substance abuse), and almost twenty percent have a personality disorder that interferes with everyday life. Eighteen percent of college students take prescription psychological medications, and fifteen percent are clinically depressed. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students.

Although the percentage of Americans confined to mental hospitals has declined since the 1960s, the numbers of those seeking professional help has increased. Still, nearly three-quarters of those with serious psychiatric problems never get professional help, turning instead to alcohol and other forms of self-medication.

The statistics indicate that many of us are going crazy. But, asks Dionysus, who defines sanity? For decades, Benjamin Rush’s nineteenth-century definition prevailed: “…an aptitude to judge of things like other men, and regular habits, etc.”

But for those considered abnormal, Rush, the father of American psychiatry, advised, “…TERROR…should be employed in the cure of madness…FEAR, accompanied with PAIN, and a sense of SHAME, has sometimes cured this disease.” His name evokes the history of the brutal treatment of the mentally ill, in which all manner of torture was used well into the 20th century, including mustard baths, application of hot irons, “punishment chairs,” bleeding with leaches, electroshock and “refrigeration therapy.”

Freud saw sanity as the abilities to love and work. This meant fitting in with one’s cultural norms. One of his disciples stated that the goal of psychoanalysis is “the eradication of mystery.”

The libertarian psychotherapist Thomas Szasz, however, insisted that most mental illness is composed only of behaviors that psychiatrists – white, middle-class men – disapprove of.

Dionysus also asks, who should die because they commit crimes even though they know right from wrong? America no longer executes the mentally retarded, and Psychiatry has drawn the I.Q. line at 70. Paula Caplan, however, argues that I.Q. testing is notoriously inaccurate:

Like ‘intelligence,’ ‘retardation’ is a construct. Why should anyone decide that a prisoner who scores 69 on an IQ test should live but one who scores 71 should die?

We know what is acceptable by identifying those who, as John Jervis writes, “contradict the official self-image, disturb its clarity, question its necessity.” “Female” behavior has long been the baseline. Doctors committed nineteenth century women to asylums for such “symptoms” as flirting too much, refusing to marry men chosen by their fathers and excessive religious fervor. Asylums, writes Phyliss Chesler, functioned as “… penalties for being “female,” as well as desiring…not to be.” The gender imbalance still exists, even if such behaviors are no longer valid excuses for institutionalization. It remains safer for women to turn their dissatisfaction inward through depression rather than outward through violence (more typically male behavior). One in eight women will be diagnosed with depression during their lifetime, and they are twice as likely as men to receive electroshock treatment.

Middle-class women utilize private therapy, but often consider hospitalization in midlife (if they can afford it), when they are both overworked and beginning to feel sexually and maternally expendable. Chesler claims that, prior to 1970’s feminism, most women simply gave in to mixed expectations of their social condition, which provided them few options. Now, single, divorced, and widowed women all have lower rates of mental illness than married women, and the reverse is true for men. Poor women, however, have few options but the penal system and state mental hospitals.

If “female” behavior – collective, emotional, “hysterical” – defines the shadow of our value system – and of the prejudices of psychology – then the perspective within the pale is American radical individualism, which emphasizes the individual differentiating out of the family – the heroic ego, as James Hillman described, in a hostile world.

Part Two

Those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end, for they do so with the approval of their own conscience. – C.S. Lewis

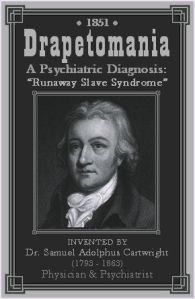

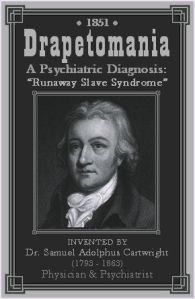

Especially in times of great change, society manipulates definitions of sanity when unstable social conditions require scapegoats. “Drapetomania” explained the “irrational tendency” of black slaves to flee captivity. Benjamin Rush diagnosed rebels against federal authority with “anarchia…excess of the passion for liberty…a form of insanity.” The dominant medical perspective still reflects Puritan prejudices when it defines some children as born “neurologically defective” (a more acceptable term than “original sin”).

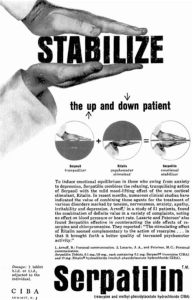

But in America these conditions occur (or are identified) within the all-encompassing situation of late-stage capitalism, in which the most corrupt industries – most especially Big Pharma – have been quick to take advantage of human misery, financially endowing university departments of Psychiatry and selectively funding pro-drug research programs. In 2006, it accounted for thirty percent of the American Psychiatric Association’s $62.5 million in financing. About half of that money went to drug advertisements in psychiatric journals.

(Americans may be ill-educated on these issues, but they are not stupid. Mass resistance to the Covid vaccines is not simply a function of religious intolerance, anti-science ignorance or right-wing propaganda, but very often of fear of corrupted science. In 2015, the editor of the leading medical journal The Lancet, cited “studies with small sample sizes, tiny effects, invalid exploratory analyses, and flagrant conflicts of interest,” concluding that “much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue.”)

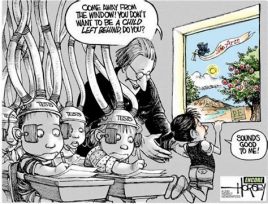

Big Pharma provides the answer to nature gone wrong (previously cured by baptism at birth). In the U.S., 2.5 million children and 1.5 million adults manage hyperactive and attention deficit behaviors with Ritalin, with 17 million prescriptions per year. Peter Breggin, MD, however, writes that the Attention Deficit (ADD) diagnosis was developed specifically to justify “the use of drugs to subdue the behaviors of children in the classroom.” The U.S. produces and consumes ninety percent of the world’s Ritalin, most of which is given to our children, including ten percent of all ten-year-old boys.

However, when we hear of epidemics of depression and anxiety, we need to ask whose interest that impression serves. Cui bono? Follow the numbers: between 1995 and 2002 the number of children and teens diagnosed with depression doubled. American doctors are five times more likely than British doctors to prescribe antidepressants to minors.

Follow the politics: while minimizing poverty, irrelevant schooling and epidemic violence, the psychiatric priesthood maintains a symbiotic relationship with the pharmaceutical industry, which annually spends $25 billion on marketing worldwide and employs more Washington lobbyists than there are legislators. Prior to the Covid pandemic, the top class of drug by revenue ($14.5 billion in 2009) was antipsychotics. In 2008 the New York Times reported on Psychiatrist Joseph Biederman:

A world-renowned Harvard child psychiatrist whose work has helped fuel an explosion in the use of powerful anti-psychotic medicines in children earned at least $1.6 million in consulting fees from drug makers from 2000 to 2007 but for years did not report much of this income to university officials.

Due in part to Biederman’s influence, the number of American children and adolescents treated for bipolar disorder increased 40-fold from 1994 to 2003.

Simply put, madness is big business: labeling others (Others) as sick, scaring parents and pushing (prescribing) drugs as the only cure. Each edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) has included more mental disorders than the previous one.

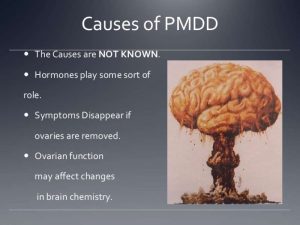

One of those “disorders”, “Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder” (PMDD), has defined premenstrual emotional swings as mental illness. A 1992 study took the symptoms listed for PMDD – then called Late Luteal Phase Dysphoric Disorder (LLPDD) – and asked three groups of people to document every day for two months the symptoms they experienced. The groups were women who reported severe premenstrual problems, women who reported no such problems, and men. The answers did not differ among the three groups.

Why did the DSM demonize a natural condition? Follow the money: shortly before, with the patent on Prozac about to expire, its manufacturer, Eli Lilly, rebranded it as “Sarafem” and marketed it as the cure for this new condition. The DSM complied, and recommended antidepressants as the only psychiatric therapy for PMDD. Lilly’s patent on Prozac – and its profits – were extended for seven years.

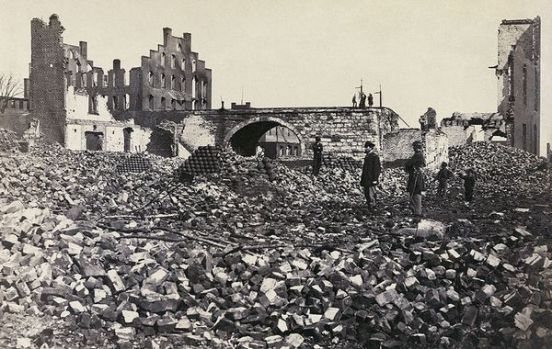

Deinstitutionalization reduced the asylum population from 500,000 in 1955 (half of all hospital beds) to around 60,000 in 2010. But Reagan-era budget cuts decimated the community mental health systems that had supported the released patients, instantly creating a population of tens of thousands of homeless people. Now, our largest warehouses of the mentally ill are the Los Angeles and Chicago jails.

Drastic overbuilding of hospitals in the 1970s left many institutions in serious financial trouble. Psychiatry provided the answer to this problem in 1980 with new diagnoses like “oppositional defiant disorder.” Marketing campaigns convinced thirty thousand families that only private hospitalization would keep their children from suicide. Ten years later, six times more adolescents – primarily white and middle-class – were confined to locked psychiatric wards. Skeptics, however, called the new disease “KID” (Kid-with-Insurance Disorder), pointing out the amazing rate of “recovery” once the insurance ran out and parents had to start paying out-of-pocket.

But in public facilities, the numbers of teens have actually decreased, because minority kids go to jails and, unsurprisingly, receive no treatment at all.

Enforced hospitalization exemplifies the shadow of a society that claims personal liberty as its highest value. The “therapeutic state,” says Szasz, uses psychiatric justifications to strip individuals of their rights. It creates two classes: those who are stigmatized as crazy and subject to coercive intervention, and “us,” whose conventional behavior and well-concealed abnormalities indicate our innocence. No one else – neither priest nor judge – has the psychiatrist’s power to have someone committed, even if he came into his office of his own free will:

Only in psychiatry are there ‘patients’ who don’t want to be patients…If you’re in a building that you can’t get out of, that’s not a hospital; it’s a prison.

Certainly, many of the involuntarily committed are dangerous to themselves or others. Yet too often, psychiatrists function as the Church once did, as agents of the state, as gatekeepers who determine who is or isn’t the Other.

Part Three

The ideal of growth makes us feel stunted; the ideal family makes us feel crazy…So long as the statistics of normalizing developmental psychology determine the standards against which the extraordinary complexities of a life are judged, deviations become deviants. – James Hillman

It is possible that poet Theodore Roethke romanticized suffering when he asked, “What is madness but nobility of soul at odds with circumstance?” Yet we can’t consider mental illness outside of its social, cultural, economic and political contexts. Psychologist Mary Watkins writes, “The symptom as it appears in the individual points us also toward the pathology of the world, of the culture.” Depression is not rare among non-Western people, but it increases when they move to America. Some claim that schizophrenia is more prevalent in cultures like ours that combine high rates of poverty with low senses of social belonging.

But America adds two other factors. The first is that our characteristic American expectation of positive emotions and life-experiences makes sadness more pathological here than elsewhere. Sociologist Christina Kotchemidova writes, “Since ‘cheerfulness’ and ‘depression’ are bound by opposition, the more one is normalized, the more negative the other will appear.”

She argues that twentieth century America took on cheerfulness as an identifying characteristic. The new consumer economy of the 1920s called for cheerful salespeople who’d be careful to avoid provoking vital customers. A powerful emotional deintensification process also began at that time. The American etiquette obliged “niceness,” which excluded strong emotionality. Railroads introduced “Smile School” in the thirties. Among the dozens of self-help cheerfulness manuals, Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936) sold over thirty million copies.

In the 1950s the media industry invented special devices such as the TV “laugh track” to induce cheerfulness. Eventually, politicians discovered cheerfulness. All Presidents since Ronald Reagan smile in their official portraits. The “smiley face” button sold over 50 million buttons at its peak in 1971.

The laugh-track has a specific purpose: keep people engaged, pleasantly entertained and therefore receptive to the commercials selling them things that they don’t need. The products in the commercials are meant to create emotional associations with the artificial cheerfulness stimulated by the laugh track. In other words, since the 1950s, television (and increasingly, films and later the internet) have mediated our emotions; they’ve been telling us what to think and feel.

Ronald Laing argued that the modern family functions “to repress Eros, to induce a false consciousness of security…to promote a respect for ‘respectability.’” To be respectable is to produce, and, in America, to look cheerful while doing it. Our obsession with feeling good (“pursuing happiness”) is enshrined as a fundamental principle of the consumer society. Kotchemidova writes,

Our personal feelings are constantly encouraged or discouraged by the culture of emotions we have internalized, and any significant deviance from the societal emotional norms is perceived as emotional disorder that necessitates treatment.

She argues that Americans feel significant pressure to look cheerful in order to get a job. Once they are employed, putting on a ready-made smile is simply not enough. “Corporations expect their staff to actually feel good about the work they do in order to appear convincing to clients.”

Most advertising is in some sense selling happiness or relief from unhappiness. Despite all our “stuff,” however, our characteristic American individualism subverts social networks, making it difficult for those in emotional or spiritual crises to find containment except through drugs, religious literalism, political cults or madhouses. In a culture that remains Puritan at the core, Americans have commonly internalized the mad notion that our suffering is our own fault, and that others who appear to be happy are normal (in religious terms, “among the elect”). The cultural pressure to appear upbeat invalidates sadness, pathologizing it into depression. Thus, a person who feels sad may also feel guilty.

Or angry. Very angry. The second factor that American culture adds to the brew of madness is our radical individualism with its characteristic expectations of constant growth and social mobility. (For lengthy speculations about the myths of progress and growth in Chapter Nine of my book.) When our assumptions of social mobility are revealed as fiction, the hero encounters his opposite – the victim, or the loser – within himself, and we become what we really are (except for Nazi Germany), the most violent people in history. American crime and violence are natural by-products of our values, alternative means of social mobility in a society where “anything goes” in the pursuit of success. In “A Mythology of Bullets”, mythologist Glen Slater writes that “America has little imagination for loss and failure. It only knows how to move forward.”

We go ballistic when we can only imagine moving forward and that movement is blocked. Then guns become the purest expression of controlling one’s fate. As such, they are “the dark epitome of the self-made way of life.” We as a people may well dream bigger dreams than other peoples. With great possibilities, however, come great risks. Gaps between aspiration and reality – the lost dream – are also far higher here than anywhere else. When we don’t meet our expectations of success, when that gap gets too wide, violence often becomes the only option, the expression of a fantasy of ultimate individualism and control. In this sense, the Mafia is more American then Sicilian, and the lone, mass killer (almost all of whom have been white, middle class men with no criminal background) is an expression of social mobility gone bad.

Gun violence throws us back onto some of the basic questions posed by Dionysus: Why are convicted murderers not considered insane? Why do we punish criminals instead of rehabilitating them? We could also add: Is a depressed young man who massacres schoolchildren or Black churchgoers, or who drives his car into a crowd of BLM protesters evil or sick? Should he be punished or given compassionate treatment?

Depression has been defined as “disturbance of affect.” But “affect” is culturally determined. Positive expectations and assumptions of the right to the “pursuit of happiness” make feelings of sadness and despair more pathological in America than anywhere else. Feeling good has become no longer simply a right, but a duty. If we cannot accept normal depression, we may become ashamed and alienated from ourselves, we may well experience the rage that often lies below the depression, and in true American fashion, we may search for scapegoats to punish.

Depression, violence, a culture that cannot grieve and poor medical standards, meet Big Pharma. The gatekeepers who update the DSM comply with these prejudices, having reduced acceptable, “normal bereavement” from one year to two months. Psychiatrists administer drugs instead of psychotherapy in over seventy percent of patient visits. Frederick Crews writes,

Those stigmata, furthermore, are presented in a user-friendly checklist form that awards equal value to each symptom within a disorder’s entry. In Bingo style, for example, a patient who fits five out of the nine listed criteria for depression is tagged with the disorder. It is little wonder, then, that drug makers’ advertisements now urge consumers to spot their own defectiveness through reprinted DSM checklists and then to demand correction via the designated pills.

The percentage of patient visits to a psychiatrist involving any psychotherapy fell from 44% in 1996 to 29% in 2004. Bruce Levine argues that Psychiatry has increasingly replaced psychotherapy with “medication management,” which largely consists of symptom assessment and prescription updates. It typically takes 10 or 15 minutes and is scheduled every two to three months, rather than weekly, as is psychotherapy. Insurance companies favor medication management because it is so cheap, and drug companies favor it for obvious reasons. Psychiatrists themselves favor it because they can make far more money with it. Those who offer only medication management routinely make nearly triple the income as do those who provide mostly psychotherapy. And when drugs don’t work, some still prescribe electroshock for children. Madness is big business.

Part Four

If therapy imagines its task to be that of helping people cope (and not protest), to adapt (and not rebel), to normalize their oddity, and to accept themselves “and work within your situation; make it work for you” (rather than refuse the unacceptable), then therapy is collaborating with what the state wants: docile plebes. Coping simply equals compliance. – James Hillman

Men are so necessarily mad, that not to be mad would amount to another form of madness. – Blaise Pascal

In the 1950’s Time Magazine’s gatekeepers described left-wing comedians Mort Sahl and Lennie Bruce as “sicknicks.” But simultaneously, hipsters used “crazy” in positive terms. The powerless attain some control by inverting language, as 1960’s Black people used “bad” to replace “good” and, more recently, teenagers recently indicated approval with “sick.”

Clearly, however, madness predates capitalism, and economics doesn’t explain it all. Enter Dionysus. The term bakkheuein (“maddened by Dionysus”) occurs in over half of the extant works of Greek Tragedy. “Divine madness” came as a gift from the gods. The Muses inspired poetic madness, Apollo was the god of prophetic madness and Aphrodite gave erotic madness.

From the Greek perspective, the gods reveal ourselves to ourselves, and madness is a fundamental, archetypal aspect of the psyche. Dionysus, the mad god himself, was the patron of ritual madness. Classicist Walter Otto understood both the Greek world and ours:

A god who is mad! …There can be a god who is mad only if there is a mad world which reveals itself through him.

Plato distinguished two basic kinds of madness: “one arising from human disease, the other when heaven sets us free from established convention.” This insight, however, hardly exempts us from the necessarily painful experience of transformation. Another classicist, E.R. Dodds, described the conflicting emotions involved: “…a mixture of supreme exaltation and supreme repulsion… at once holy and horrible, fulfillment and uncleanness, a sacrament and a pollution.”

This ambivalence describes Dionysus himself, known both as the cause of madness (Bakkheios) and its cure, Lusios, “the Loosener.” And it recalls one of his stories: the Titans (progenitors of the gods) captured the baby Dionysus, tore him to pieces and devoured him. Athena saved the heart and gave it to Zeus, who ate it. Out of this Dionysus the God was reborn. Zeus struck the Titans with thunder and burned them to ashes, from which humans were formed. Therefore, humans have inherited something of the divine from Dionysus, and something evil from the Titans. The titanic aspect – excessive, manipulative, patriarchal, inflated, violent – is expressed in the madness of mass society, which nearly always attempts to repress the irrational, androgynous and potentially joyous, Dionysian aspect.

Which madness do we follow? Hillman summarized the old thinking: “…insanity is following the wrong god.” In any case, repressed diversity ultimately re-appears as psychopathology. Raphael Lopez-Pedraza wrote, “Illness is essentially repression.” But the myths of Dionysus take this idea even further. In story after story, those who deny the divinity of this Other call upon themselves a terrible fate. He drives them raving mad – mad enough to slaughter their own children by mistake.

Many of these stories reflect historical opposition to his cult. But what are the archetypal implications? Why does the gentle god of ecstasy arrive with such ferocity? King Lykourgos persecuted young Dionysus, who hid under the sea, protected by goddesses. He re-emerged, no longer ecstatic but furious, driving Lykourgos mad enough to kill his own son. Boutes, who chased the maenads into the sea, went mad and drowned himself. Perseus killed some of Dionysus’ followers. The god responded by entrancing the Argive women, who devoured their own infants. The three daughters of Minyas scolded Dionysus’ devotees. Disguised as a maiden, he warned them of their folly, but they ignored her. So he changed himself into a lion, then a bull and then a panther. Ivy and vines grew over their looms. In their madness they dismembered and devoured one of their children, then roamed the mountains until Dionysus finally changed them into birds.

When Dionysus approached Eleuther’s three daughters wearing a black goatskin, they rejected him and he drove them mad. They were cured only when their town instituted the worship of Dionysus Melanaigis (“of the black goatskin – in league with the dead.”) Similarly, King Proetus’ three daughters went mad, infecting other women, and all left their families. Some ate their own children and wandered as cows in heat, fitting partners for the bull-god. Zeus asked Ino and her husband Athamas to hide the baby Dionysus from Hera. But she discovered the ruse and struck them with madness. Athamas killed one of his sons, thinking he was a stag, and Ino threw the other into boiling water.

His most famous story is Euripides’ Bacchae, in which King Pentheus persecutes him and his followers. It ends when Dionysus drives the women of Thebes (led by Pentheus’ own mother, Agave) insane, and they mistakenly kill and dismember Pentheus. But casual readers of the play and even many classicists often miss a crucial distinction between the women who choose to follow Dionysus – the Bacchants – and those – the Maenads (from mania, “possession”) – whom he drives insane because they have resisted him.

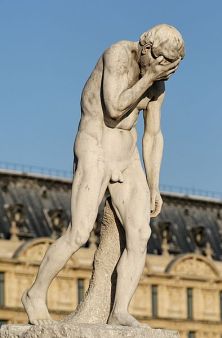

The Maenads attacking Pentheus

The essential message I take from these stories is that a soul – or a culture – that refuses to welcome and honor its irrational aspects will inevitably turn its rage onto its own children (or inner children). How else can we possibly explain a society such as ours, that condemns at least 25% of its children to poverty simply because their parents can’t find decent work?

It might have been different, writes Nor Hall: “Had they joined the Dionysian company willingly, they would have enacted this state of wild abandon within a protective circle.”

Robert A. Johnson wrote,

We hear a screech of brakes and a crash…Cold chills go up and down our spine; we say “How awful!” – and run outside to see the accident. This is poor-quality Dionysus…what happens to a basic human drive that has not been lived out for nearly four thousand years.

When society agrees on a definition of Apollonian “normality” peopled by contented, comfortable, positive-thinking citizens working or recreating in the mild sunlight of a suburban world, we naturally, perhaps desperately, long for a visitation from the darkness.

I suggest that America, with its history of unrepentant slavery, aggressive genocide, imperial aggression and puritanical sexuality, has and continues to identify – and demonize – the Dionysian impulse with racial and sexual minorities. And our unique mythology of innocence functions to keep the white middle-class safely within the pale of acceptable belief.

“Poor-quality Dionysus” indicates the return of the repressed, a subject I address in Chapter Four of my book, Madness at the Gates of the City: The Myth of American Innocence. “Mad,” after all, has other meanings: angry, rabid. If we think of some mental illness as a socially powerless, alienated person’s attempt to unite body and feeling – to resurrect Dionysus and the other gods from the underworld – or if we substitute “uninitiated” for “mentally ill” – madness can be part of a natural if painful process of restoring balance. Curiously, this is precisely how African Shaman Malidoma Somé describes the purpose of ritual.

As Jung taught, the old gods can only return as symptoms. This impacts many women who feel compelled to repress feminine values. In taking on the compulsively driven, cutthroat standards of the corporate world, they are like the Bacchants who cry out to Dionysus for release. Marion Woodman wrote that when women elevate thinness at any price to the highest value, the repressed gods take vengeance through somatic distortions like obesity or anorexia:

The Dionysian “madness” inherent in compulsive eating may be a modern expression of what was earlier known as “possession” and in more recent years as “hysteria”…The symptom may be the cross on which thousands are forced to writhe because they are unaware of the androgynous god striving towards consciousness.

No one is exempt from the modern condition. We all suffer from the collective emotional effects of the long-term shift from the indigenous, rural, pagan world to monotheism, urbanization and industrialism. We are all, to some extent, alienated from the Earth and from our bodies. We are all, in indigenous terms, unwelcomed, unacknowledged and uninitiated. We are the net products of a process that has taken some 200 generations to unfold, reaching its peak with many of our recent political and corporate leaders, whom Erich Fromm described as “necrophiliacs”:

…the necrophilous person loves all that does not grow, that is mechanical. …driven by the desire to transform the organic into the inorganic, to approach life mechanically, as if all living persons were things…The necrophilous person can relate to an object – a flower or a person – only if he possesses it…if he loses possession, he loses contact with the world…He loves control, and in the act of controlling he kills life.

But long before the advent of Trumpus and his mystifyingly huge popularity, Psychiatrist Russel Lee studied the political leaders of World War I and concluded that every one of them was bonkers: “The very qualities of egocentricity and megalomania characteristic of many psychoses are precisely those that lead men to aspire to high office.” He describes psychopaths as “superficially charming, intelligent people who don’t feel deep emotions and lie about almost everything because they neither understand nor care about others,” and argues that “in today’s rapidly changing business world, increased corporate rewards for risk taking and nonconformity can offer the psychopath faster career movement than before.”

Large-scale denial of the sorrows of our history and long-term identification with such men and other celebrities contributes to this condition. Nearly every American suffers from suppressed grief, which returns as anxiety, addiction, narcissism, depression or merely a vague sense of guilt.

The mad culture, led by madmen, continually requires new scapegoats to sacrifice and restore our innocence. Three million Viet Nam veterans (and now, Iraq and Afghanistan veterans) carry the burden of delayed stress for us all. Movies that portray them as ticking time bombs allow us to consider memory’s immense power without confronting its universal application. And, warns Dionysus, we are all ticking.

But who best displays our national shadow for us but our children, all of whom come into this world with the archetypal expectation of being welcomed and celebrated, but who encounter this madness? Consider their clothing: baggy pants drooping below the waste, butt cracks showing; untied shoes; oversized, black, hooded sweatshirts. This depressed style of presentation common among adolescents everywhere, regardless of ethnicity or social class, cries out: Look at us, look at what we carry for you!

Part Five

Harmless violence where no one gets hurt breeds innocence…the innocent American is the violent American. – James Hillman

In a mad world, only the mad are sane. – Akira Kurosawa

So many of our children, and all depressed people, carry the shadow of our manic celebration of progress, growth, heroism, extraversion, cheerfulness, grandiosity and radical individualism, below which is a bedrock layer of Calvinist hatred of the body. They are the canaries in the mineshaft, showing us that the more popular culture emphasizes these characteristics, the more depression spreads. We who channel the madness into fundamentalism, consumerism or war fever may feel temporarily welcome among the elect, while the Others who cannot do so are proof to us of our righteous standing and innocence.

At least since the beginning of the nuclear age (I write this post on Hiroshima Day, 2021), popular culture has hesitantly acknowledged this condition. Novels like Catch-22, Slaughterhouse Five and One Flew Over the Cookoo’s Nest hinted that modernity, with its stressful pace of change and nearly constant fear and anxiety, is mad, or maddening. But even four hundred years ago, the first modern novel, Don Quixote (published two years before the English invaded Virginia), took madness as its basic theme. More recently, Paul Shepard described an “epidemic of the psychopathic mutilation of ontogeny” – in simple terms, we don’t grow up the way nature intended anymore. We are, by indigenous standards, uninitiated, children.

Medications and alcohol level our highs and lows, effectively casting out both angels and demons. Still, perhaps forty million Americans experience anxiety.

Clearly, any caregiver hopes to reduce suffering. “Successful treatment,” writes E.F. Torrey, “means the control of symptoms.” But when psychotherapy merely attempts to recover a sense of “productive normalcy,” that condition which is itself a cause of our unhappiness, it becomes yet another effort to recover lost innocence – and a condemnation of an archetype ruled by the mythic image of Dionysus.

John Zerzan argues, “To assert that we can be whole/enlightened/healed within the present madness amounts to endorsing the madness.” This is partially a question of awareness, much of which is conditioned by the media, whose primary purpose, lest we forget, is to sell us to advertisers.

On the one hand, we collude, veiling both our complicity and our suffering. On the other, media obsession with crime and terrorism produces an on-going sense of anxiety. This decades-long, roiling, alternating sense of both paranoia and denial describes our peculiarly American form of collective madness.

This has occurred – since long before 9/11 – in three major ways. On the positive side, pundits present a unified front of reassurance and denial: Global warming is a fiction, racism is a thing of the past, Iraqis welcome us as liberators, etc. Television idealizes the nuclear family and small-town values in cloying commercials that convey a ubiquitous, Disney-style innocence. Sit-com protagonists are usually young, attractive, middle-class whites whose problems – caused individually, not systemically – consistently resolve themselves. Reality shows are Social Darwinist fables in which the ablest triumph, but everyone gets a hug. It’s all good. Michael Ventura, however, measures how deeply “…people know that ‘it’ is not all right…by how much money they are willing to pay to be ceaselessly told it is.”

The negative side involves both sanitized violence as well as a constant atmosphere of low-level dread: illegal immigrants, teen pregnancy, drugs, urban violence, satanic cults, child molesters, “security” rituals at airports (do we laugh or cry when we give up our water bottles?) and TV news, where “if it bleeds it leads.” By the time the average student graduates from high school, he/she has viewed 18,000 TV murders. Fifty-five percent of local newscast coverage of children concerns violence. As a result, three out of four parents worry – unnecessarily – that strangers will kidnap their children. (Crimes in which a stranger snatches a child are actually quite rare). Between 1990 and 1998, as murder rates declined dramatically, murder stories on network newscasts increased by 600 percent, not counting O.J. Simpson stories. We can theoretically take two populations of children and predict that, as young adults fifteen years later, those who watch more TV will be more violent than those who watch less. Ten percent of women in their forties expect to die of breast cancer, while the real odds are one in 250.

Ignoring race and the political-economic sources of terrorism, we fret about issues that the media choose for us. After several generations of TV, we rarely differentiate between ignorance and apathy: I don’t know and I don’t care. Meanwhile, the Dionysian scapegoat – defined as lacking the essential Protestant virtue of self-control – presents a tempting return to innocence. Everyone can avoid discussing gun control when newspapers editorialize, “It’s Not Guns, It’s Killer Kids.” We dread the disturbed individual, the bad seed, rather than systemic inequities. So our emphasis on individualism links happy denial to this constant, low-level background of fear. Periodically, when actual – or contrived – episodes of terror evoke the old frontier paranoia, we jettison our moral and democratic priorities like recycled computers.

The third factor is our electronically enhanced mania. In most public, urban spaces – stores, shopping malls and sports arenas – we endure unrelenting onslaughts of loud music, blinking lights and high-definition visual images. Often the atmosphere approaches that of gambling casinos, which are deliberately designed to create altered states of consciousness so as to heighten anxiety and encourage shopping. However, this anxiety never fully dissipates, and we acclimate to greater levels of it.

This awkward combination of fear, denial and over-stimulation has ruled our consciousness during the seventy years of television, which was born amid both consumerism and McCarthyism. From the start, Lucille Ball diverted us while Richard Nixon admitted, “People react to fear, not love.”

The roots of American paranoia go back to the original confrontation of settler colonists and natives. Ever since, we’ve held the contradictory notions of chosen people and eternal vigilance. If we are attacked, the release of disillusioned energy drives us to engage in, condone – or happily watch – extreme violence. Our lost innocence – we have done so much good – justifies our Biblical fury. Bad dreams constantly interrupt our 400-year sleep of denial, and we awake exhausted.

The only other comparable emotional mix is the universal war experience of long periods of boredom interrupted by periods of absolute terror. Psychologist Edward Tick writes, “This twin dimensionality…makes it surreal, almost hallucinatory. Horror is married to boredom, fascination to putrescence.”

For forty-five years we’ve flocked by the millions to disaster films. This genre works both sides of the fear/denial dichotomy by heightening fear of apocalyptic retribution and then cleanly resolving the threat through the intercession of selfless heroes.

The pathology of this condition is that it subjects us to overwhelmingly persistent messages that completely discount our emotional, intuitive and moral intelligence. It is the same wounding that children receive if adults tell them that they (the children) don’t really feel something – and this happens all day long, every day of our lives. We all learn this: My ways of evaluating reality are failures. And, since failure in America is always moral failure, I am a failure. As Jerry Mander writes, “Television isolates people from the environment, from each other, and from their own senses.” The result is epidemics of depression, self-medication through substance abuse, consumerism and fundamentalism – and a peculiar aspect of “poor-quality Dionysus,” the distanced, vicarious enjoyment of violence.

After 9/11 the mad fusion of fear and denial reached cliché proportions with color-coded terrorist alerts. Americans awakened daily to a degree of apprehension that shifted according to un-confirmable “findings.” However, most (employed, pre-recession, white) people had the existential experience of nothing being particularly wrong. William Rivers Pitt documented at least five occasions when damaging reports of administration malfeasance emerged in the media, only to be forgotten when the government quickly raised the terror alert. By 2006, 79% expected another terrorist attack soon, but only 20% were personally concerned. In psychology experiments, such intermittent reinforcement drives lab animals insane. And it drives humans to release the tension by sacrificing a scapegoat.

Our characteristic American denial of death also ensures that we carry great loads of unexpressed grief. Malidoma Somé observes: “A non-Westerner arriving in this country for the first time is struck by how… (Americans) pride themselves for not showing how they feel about anything.”

This succinct, tribal definition of alienation brings us back to the loss of the Dionysian experience. If we can neither grieve nor tolerate the vision of the dark goddess and her bloody, dismembered son, then we can’t experience joy either. We tolerate pale substitutes: romance novels, horror movies (often with characters who refuse to die), the spectacles of popular music and sports, Sunday church and happy endings. We learn early to emphasize the light (“lite”) and exclude the dark.

It follows that we’re fascinated with media (mediated) violence. Death’s repressed experience re-emerges in images. As suppression of sex creates pornography, American attitudes toward death result in what sociologist Ellen Zinner calls “necrography:” highly sensationalistic, electronic mayhem. This substitute gratification allows us to meet death and remain unharmed; thrill and pseudo-terror replace grief. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, however, insisted that our denial of death “has only increased our anxiety and contributed to our… aggressiveness – to kill in order to avoid…facing of our own death.”

How does this happen? Subject to vast, impersonal, forces impacting us from remote, Apollonic distances – government, corporations, junk phone calls, invisible viruses – most of us refrain from exploding in personal violence. By tolerating long-distance violence against the Third World, however, we safely displace our rage upon the Other.

America was characterized from the start by extreme violence. It was present in the “idea” of America – not the abstract ideals of the founding fathers, but the projection of darkness onto the Other in the seventeenth century. By the Industrial Revolution, white Americans had been slaughtering Indians and enslaving Africans for two centuries. Mass media certainly amplified alienation. But the seed of depression and long-distance violence fell on fertile soil that had been well prepared.

The final factor is TV and social media, which help us remain sheltered from the world and our impact upon it. “We are so desperate for this,” writes Ventura, that we are willing to accept ignorance as a substitute for innocence.” On the other hand, even as programming perpetuates fear, it desensitizes us to the actual effects of violence. We innocently observe and quickly forget.

Never having confronted our own suffering, we must find a way to see it. We are, however, so abstracted that we don’t care whether death occurs on a three-inch game-boy, on an IPhone or in a Palestinian street. And our shell of innocence insulates us from our complicity: the nation that has more handguns than citizens is shocked – shocked! – each time a (white) teenager massacres his schoolmates.

Somé describes the consequences of refusing to grieve: “People who do not know how to weep together are people who cannot laugh together.” To paraphrase Mexican poet Octavio Paz: a culture that begins by denying death will end by denying life.

Part Six

If you talk to God, you are praying; If God talks to you, you have schizophrenia. If the dead talk to you, you are a spiritualist; If you talk to the dead, you are a schizophrenic. – Thomas Szasz

I talk always to the man who walks along with me; men who talk to themselves hope to talk to God someday. – Antonio Machado

We have no tradition of shamanism. We have no tradition of journeying into these mental worlds. We are terrified of madness. We fear it because the Western mind is a house of cards, and the people who built that house of cards know that, and they are terrified of madness. – Terrence McKenna

Madness need not be all breakdown. It may also be break-through. – Ronald Laing

A major function of the myth of American innocence is to channel our grief toward either “Titanic” distractions or depression. From the perspective of shaman Martin Prechtel, depression is, quite simply, “the refusal to grieve…petrified sorrow.” Curiously, in the Tutzujil Mayan language of his Guatemalan people, the word for alcohol translates as “the Tear Loosener.”

Many men are well aware of this condition. One of the most common statements at men’s retreats is: “I haven’t cried in thirty years – and I won’t start. If I did, it would never stop.” It leads to a view of madness as the fine line between delusion and revelation, or between the return of the repressed and spontaneous initiation – the territory of The Bacchae.

The return of Dionysus can appear as psychological dismemberment. But in modern life, such experiences typically occur outside of any ritual containers. Schizophrenics enter liminal space alone, without guides. Freud felt that psychoanalysis couldn’t help them, and psychiatry now diagnoses them as caused by bio-chemical imbalances or genetic defects that require lifelong drug treatment to repress the symptoms.

Jung, however, saw psychosis as a natural renewal process, a spontaneous, unconscious attempt at radical inner transformation, or metanoia. John Weir Perry argued that we should “regard the term ‘sickness’ as pertaining not to the acute turmoil but to the pre-psychotic personality…in need of profound reorganization.”

“Chronic schizophrenia” is created by society’s negative response to what is actually a perfectly healthy and natural process…It’s a well-known fact that people can and do clear up in a benign setting. Actually, they can come down very quickly. But if some of our cases had gone to the mental hospital, they would have been given a very dire message: “You’ve had a mental breakdown. You’re sick. You’re into this for decades, maybe for the rest of your life!” and told “You need this medication to keep it all together.”

Many of his patients described visions consistent with the ancient symbolism of kingship and initiation. Joseph Campbell wrote that such fantasy “perfectly matches that of the mythological hero journey.” From this perspective, madness becomes an opportunity, under the dubious guidance of the mad god himself.

Mircea Eliade described shamanic initiations in Siberia: “The profane man is being ‘dissolved’ and a new personality…prepared for birth.” Initiates are torn apart: “They ‘die’ and…are cut up by demons …their bones are cleaned, the flesh scraped off.”

Similar images can appear in the visions of modern people who descend into madness. “If they are not supplied from without,” writes Campbell, “…they will have to be announced again, through dream, from within.”

What is being “dis-membered”? In America, and often at midlife, it is phallic, isolated, heroic masculinity that breaks down for a new identity to emerge. Dismemberment has one advantage, writes Nor Hall: “…we get to see all the parts.”

In historical accounts of persons who went mad but also had religious experiences, most took their revelations literally. They had visions of death, apocalypse, sexual inversion, and rebirth – all images of initiation. Those who did recover developed a poetic way of thinking past the literal to the metaphoric. In 1830 John Perceval wrote, “The spirit speaks poetically, but the lunatic takes the literal sense.” Hillman observes, “Only as Perceval becomes humorous, doubtful and ironic does he become sane…he moves from gravity to levity.”

Author Dick Russell offers a deeply moving account of his son’s long-term dance between a schizophrenia diagnosis, medication and African shamanic initiation in My Mysterious Son.

But Perceval was an exception. Most get stuck in “chronic liminality,” wrote Robert Moore. In the myth of Ariadne, many heroes entered the underground labyrinth, only to be killed by the Minotaur. Theseus defeated it because he was grounded; he had kept in contact with the world above by means of Ariadne’s thread. It enabled him to return to the light (normal consciousness) after completing his task. Those who have no thread of connection to community remain below in that “labyrinth of transformative space,” but only partially transformed. Thus, says Moore, many pathological states are merely failed initiations. The danger is that approaching the symbolic brush with death of initiation can evoke literal death. One of his clients was lucid enough to say, “I need to die, before I kill myself.” Seven centuries earlier, when it was more common to think metaphorically, Rumi advised, “Die before you die.”

Until the seventeenth century, Europeans believed that madmen were close to the unseen world and accepted them within the community, rather than banishing them to the margins. Traditional West Africans still perceive distress as a call for help: madness is a sign that the community (who know nothing of “family systems therapy”) is sick. They perceive madmen as undergoing crises resulting from the activity of spirit and protect them, hoping that their healing will benefit the community. To them, a sick world speaks through the most sensitive of us.

Perry and Laing attempted to provide just this kind of ritual space in the late 1960’s and 1970’s. The therapeutic community movement (followed later by the Spiritual Emergence Network) aimed to support people while they broke down and went through spontaneous healing, rather than reinforcing the existing ego defenses that maintained the underlying conflict.

But can men transform themselves – by themselves – in a world that lacks real community? Or, to pose the question in ritual terms: Can uninitiated older men initiate younger men? Shortly before killing himself, Ernest Hemingway wrote, “What do you think happens to a man going on 62 when he realizes that he can never write the books and stories he promised himself?…If I can’t exist on my terms, then existence is impossible.”

Suicide was his failed initiation, the heroic ego’s literal response to the symbolic challenge of transformation. By contrast, James Joyce brought his distressed daughter to Jung, who could see that she was psychotic, but he was more interested in Joyce:

His ‘psychological’ style is definitely schizophrenic, but with the difference…the ordinary patient cannot help talking and thinking in such a way, while Joyce willed it and…developed it with all his creative forces.

Joyce had both the will and the talent to move his madness into art. Some just get lucky. One man, stuck in an unsatisfying life and ignorant of mythology, fell into a midlife psychosis, compelled to draw grapevines on his walls. Fortunately, a therapist introduced him to a relationship with Dionysus, and he gradually achieved healing through alliance with the right god. As Plato wrote, “…the greatest blessings come by way of madness, indeed of madness that is heaven-sent.”

Part Seven, Conclusion

The whole world is sick…and you can’t put this right by having a good therapeutic dialogue or finding deeper meanings. It’s not about meaning anymore; it’s about survival. – James Hillman

I have lived on the lip of insanity, wanting to know reasons,

knocking on a door. It opens. I’ve been knocking from the inside. – Rumi

Tourist: “Have a nice day!” San Francisco Bagwoman: “Don’t tell me what to do!”

Dionysus is an image of our dismembered soul. We see ideals in other gods, but we see ourselves in him. He reflects our diminished, modern condition. But paradoxically he also represents our instinctual, embodied, integrated, original face. “I’m looking for the face I had,” wrote Yeats, “before the world was made.”

And his unique condition is one of his gifts to us. The suffering god models the universal connection between personal wound and intrinsic purpose. Finally, he shows us the way back to wholeness – the ecstasy of being, paradoxically, outside ourselves. But with no communally accepted and ritually precise methods of accepting his invitation, we encounter ecstasy’s other face: violence and horror. Those who deny him in themselves must force him upon others, because he must reside somewhere. Then he recruits his followers from imprisoned or marginalized regions of the culture – and the psyche – those with nothing to lose.

He requires that we endure the tension of irreconcilable opposites and resist the temptation to choose. As soon as we locate him in one half of any of his polarities, we repress the other side, and it begins to plot vengeance. Each truth is a mask that conceals its opposite. He enters our lives when that opposite quality breaks out past the mask. Tragically, by that point, it is often too late to appease him.

The distinction in his stories between the Maenads and the Bacchants is crucial. Approaching the darkness in a ritual manner, within a strong communal container, we may pass through madness into a deeper sanity. The Bacchants sought a holy madness caused by – but also cured by – Dionysus. They provoked extreme emotions, but opposed the other, more destructive madness he imposed upon the Maenads who had refused him. They engaged in the first to avoid the second, losing their minds to become sane.

Fifth-century Athens incorporated toned-down Dionysian rites into its religion. Among its major festivals were the Anthesteria, when he returned from the underworld, and the Greater Dionysia, celebrated with dramatic presentations. The mad, drunken god was the patron of Greece’s most profound cultural creation, Tragic Drama. The entire male population of Athens crowded together in the theater in broad daylight. Confronted with irresolvable conflicts, they suffered like Dionysus himself, weeping openly in a purging (katharsis) of emotion. Aristotle explained that this came through “pity and fear,” but classicist W.B. Stanford translates eleos (“pity”) as “compassionate grief.” They left the theater exhausted but revitalized, not because their differences had been resolved, nor because a victim had been sacrificed for their sins, but because they had suffered together.

The rational Greeks had great respect for the irrational. In the Dionysian festivals, solemnity and mourning combined with dancing, drunkenness, and inversion of sex roles. Wild processions with large phalluses recalled his mythic intrusions into the city – and the mind. In myth, Apollo – most exemplary Greek God of reason, beauty, exalted discourse and refined culture, voluntarily relinquished his shrine at Delphi for three months every year, inviting his raving, trailer-trash, half-brother Dionysus to move in.

What would a culture that invited Dionysus back look like? The easy answer is a replay of the 1960s: sex, drugs & rock ‘n roll, wild abandon, relaxed boundaries, blurring of gender roles, long hair, colorful clothing, anarchy, irresponsibility, spontaneity, and chaos. The Id conquers the Superego. A return to childhood and innocence…

Wait. Stop the fantasy. First, lest we forget, when the archetype emerged in the form of sexually ambivalent Rock stars, its darker side also appeared as disturbed but charismatic figures – Jim Jones, Charles Manson and David Koresh – who led modern Maenads on lethal rampages. Fifty years later, their grandchildren thought they were following Trumpus when they attacked the U.S. Capitol.

Second, I have already described the repression of Dionysus as a return to innocence. To recapitulate: the myth of American innocence is a story we tell ourselves about ourselves, a series of narratives that presents America as a beacon of freedom, equality and opportunity, the land of the new start, where anything is possible if we work hard. An America that only goes to war to defend democracy and spread the pure light of freedom. Pure. Light.

The myth, however, requires Others, from Native Americans and African slaves and their descendants to immigrants to gays to communists and the most recent Others – Muslim terrorists, Chinese, Iranians and (once again) Russians – all of whom the myth has weighed down with Dionysian characteristics. Because they have carried Dionysus, white Americans haven’t had to.

One of the epithets of Dionysus was Lusios (the Loosener), derived from lysis, also the root of analysis, which means setting free. A catalyst is a chemical agent that precipitates a process without itself being changed. Dionysus Lusios relaxed the boundaries of ego, family and society. To truly invite him back into American culture after so long is to relax those boundaries without knowing what will come in, because opening to one extreme means opening to the other as well. This is the essence of Dionysian ritual as it is still practiced in places like Haiti: create the container, invoke the gods, then get out of the way, because the ritual belongs to them. It is to invite the madness back, in hopes that it might save us from our own culturally induced, hyper-rational, violence-at-a-distance, ecology-crushing, disembodied madness.

Dionysus was the only god who died and was reborn, and the only god (except for Demeter) who grieved. Here is the clue. For long-term healing to occur, America will have to pass through, to spend much time, in the territory of grief. Indeed, mass celebration without rituals of grief reduces to mere spectacle. For Dionysus, if we truly welcome him, will open up the boundaries of innocence and memory, and through the gaps (as poet William Stafford wrote) will come

…with shouts, the horrible errors of childhood storming out to play through the broken dike.

Consider another story. Hera was disgusted by Hephaestus, her lame, ugly son, and hurled him out of Olympus. He survived and was ultimately accepted, but never forgot his early abuse. Eventually, he took his vengeance by tricking Hera into sitting in a golden chair, where she was instantly bound.

Looking at this myth, Murray Stein argues that behind the rejection of the son is the rejection of the mother under Patriarchy. The result is a cycle of mutual ambivalence and hostility. In Jungian terms, a man’s repressed feminine “marries” his shadow complex of repressed masculinity, giving the feminine an evil tone. Projected onto actual women, this feminine threat justifies his unwillingness to become emotionally intimate.

This emotional distance describes a long series of American heroes, from Daniel Boone to Rambo and beyond, who unleash their violence upon the Other, save the innocent community and then ride off into the sunset – away from women, family and all relational values.

But this story entertains the possibility of an integrated masculine identity. None of the gods, even Aries, could force Hephaestus to relent. So Zeus called upon Dionysus, who brought his wine and got him drunk. When he woke from his stupor, Hephaestus beheld Aphrodite and fell in love. They married, Hera was released, and peace was restored, all because of Dionysus.

Getting Hephaestus drunk symbolizes initiation into a masculinity that has made peace with the mother complex. Dionysus, says Stein, is both the “agent and the product of initiation…the integration of feminine spirit into masculine consciousness.”

Before he bestows these gifts, however, Dionysus will confront us with the madness of our history: the massacres, smallpox-laden blankets, slaughter of the buffalo, Indian schools, sexual repression, witch hunts, thefts of resources, robber barons, invasions, Hiroshima, B-52’s, napalm, deforestation, My Lai, Wounded Knee, Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, embargoes, assassinations, coups-d’état, slave-whippings, selling of children, castrations, Eugenics, lobotomies, rubber hoses, lynchings, police murders and stolen elections. The children ignored and the lives wasted working at unsatisfying jobs while chasing the elusive pie in the sky. The sorrows. The madness. The refusal to grieve.

An unveiled look at American history reveals an enormous catalogue of injustice. It also requires, however, that we be willing to imagine a different story. America has two histories; the first is literal, unveiled history. As painful as it is to contemplate, the truth undermines the myths of innocence and good intentions. However, if we persist in the search for the Other – Dionysus in America – we imagine a second history that psychologist Stephen Diggs calls “unconscious and alchemical.”

This is the story of America’s slow transformation and descent from the Apollonian heights of the heroic, isolated ego and the abstract, distanced killing of life. It is America’s return to its body, to the communal experience of shared joy and suffering; healing as a gift of the Other.

However, honoring Dionysus means re-learning the old rituals of mourning from indigenous people, because we are at the end of an age, and the appropriate behavior at the death of anything – especially an empire – is mourning. In the novel Beloved, Toni Morrison coined a phrase, “disremembered past” to describe that which is neither remembered nor forgotten but haunts the living as a ghost. The path to healing, for the soul and for the soul of the culture, goes directly through the recovery of memory – inviting the return of the repressed – through art and ritual.

I envision a culture that invites, invokes and celebrates its own grief. And we have only to look to the Other to re-discover the way. Consider the Jazz funerals of New Orleans. The traditional procession has two sections. The “first line” consists of officials, musicians, the family of the deceased, and pallbearers. The “second line” of local people follows behind. Everyone marches from church to cemetery, while the band plays slow hymns and dirges. This is the first stage of the familiar three-part ritual/initiation format. The second stage is internment at the cemetery, where the dead and the living briefly share liminal space.

The third stage is the procession home. Now the second line takes over and the tone changes from melancholy to ecstasy. The band (now in the rear, separating the living from the dead) shifts into high-spirited tunes, and the mourners’ slow cadence becomes wild dancing, or “second lining.” Returning to the neighborhood, they celebrate the life of the deceased; in making ritual closure with the dead, the mourners achieve re-integration into their community.

Imagine combining two Dionysian concepts, Greek Tragedy and New Orleans Funerals. Imagine mass public rituals attended by the citizenry and political leaders, in which warriors and civilians, rich and poor, women and men, white and POC, gay, straight and in between, and crazy and “normal” confront the impossible paradoxes and crimes of our history and suffer together. Imagine an American President standing in this container, begging forgiveness for his country from an African-American and a Native American. (It’s already happening in New Zealand).

Imagine the community pouring out grief for all those who died as soldiers, victims and activists, and even for the forests that once covered the continent. Imagine the relief at having finally shed tears together as a mosaic of uncommon peoples sharing the land with the Other, and the gratitude bordering on ecstasy with which an entire nation dances the “second line” on its way back home.

Imagine a critical mass of individuals willing to bear their own shadows, unlike Pentheus, the boy-king who realized too late that he was a “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.” Death before rebirth. Such madness might cure us of our madness.

For four centuries, American Dionysus has been willing to offer this nation images of its own dark soul, so it can see what it must reconcile with. Imagine if America stopped trying to force those images back outside the walls of the city, back onto the shoulders of the Other. Imagine (to use Christian terminology) that he loves us so much that he offers us the path to suffering – and eventually to laughing – together. Imagine a language like ancient Greek, whose word for “stranger” (xenos) also meant “guest.”

Before sending Pentheus to his death (by dismemberment), Dionysus pleads:

Friend, you can still save the situation.

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/85.jpeg?w=150&h=100 150w,

https://madnessatthegates.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/85.jpeg?w=150&h=100 150w,